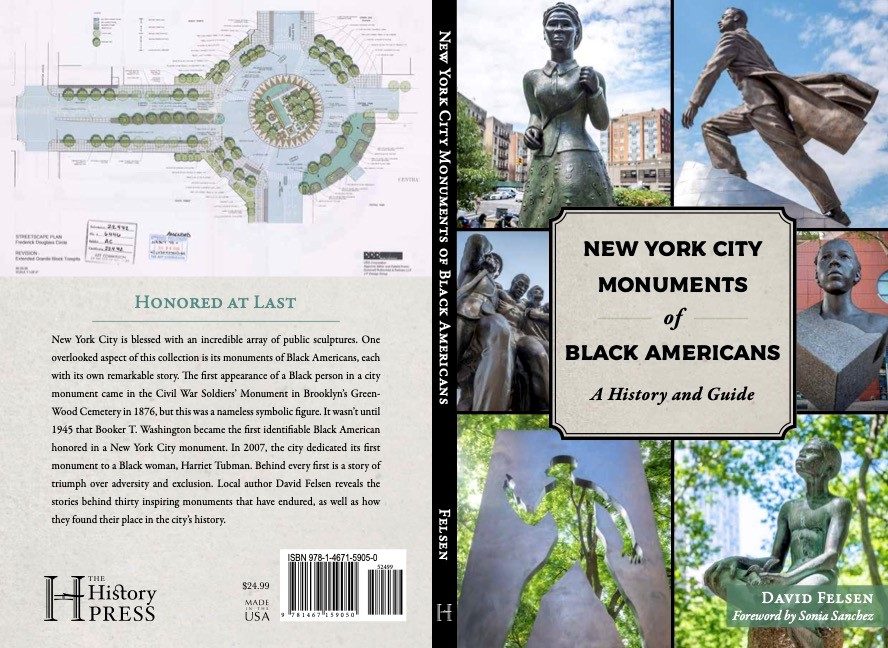

Side of Culture is pleased to introduce book reviews as a new aspect of our arts and culture coverage, especially reviews of books that relate to building and sustaining cultural communities. Our first review is of New York City Monuments of Black Americans: A History and Guide (The History Press) by David Felsen. In May of 2025, Side of Culture published an article about public art, created for public spaces, such as sculptures and murals, which serve to foster community identity, attract visitors, and encourage social cohesion. Often these murals, statues and sculptures serve to remind us of people who have made great contributions and sacrifices to better our society.

As a history teacher of high school students in New York City and in the context of the controversy over Confederate monuments in the U.S., author David Felsen became intrigued with the role of monuments in the city. He wrote, “I believe that monuments matter. They matter because they reflect the values of the city and how they have changed over time. They matter as public art, as inspiring displays of vision and skills by some of the greatest sculptors of the past century and a half, and they matter because Black Americans can see how others envisioned them in the past. For example, the first appearance of a Black person in a New York City monument that Felsen discovered was in a bronze panel at the base of the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument (1876) which depicts a nameless, shoeless former slave who helps a Union widow find her husband’s grave in the South.

Felsen is in his element when he writes this book. He currently teaches eleventh-grade American history at Avenues The World School in New York City where he must grab and hold the attention of 17 year olds. He has an MA in American History from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History at Pace University, and a BA in history from Haverford College. Before becoming a history teacher, he produced documentaries for HBO, PBS and History, formerly the History Channel. He uses his skills of observation as a journalist and of storytelling as a producer to bring alive his surroundings, all the while sharing his love of history and American culture. It appears to be a real combination of a vocation and avocation for this author.

The book is 174 pages and packed with information, including photographs of publicly accessible statues and bas-reliefs and a very helpful map. Extensive notes and bibliography showcase the well-researched nature of the Felsen’s work. It is organized into 30 chapters – each encompassing an essay focusing on one of the monuments to Black Americans “in which the faces and bodies are clearly depicted.”

The chapters present the monuments in chronological order of their creation to reflect the development of the role of Black Americans in American society from the 1870s to 2020. Felsen shows how Black Americans were perceived by artists and the public from slavery and the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument (1876) in Brooklyn, to the Civil Rights era and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial (1970) at the Esplanade Garden Apts in Harlem. Some statues appear to record the current sentiment of the time, while other monuments honor Black leaders (or influential leaders who supported Black rights) and were an effort to redress pain and wrongs of the past. Felsen quotes Black activist and art historian Freeman Murray in his 1916 book, Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture: A Study in Interpretation, ‘We cannot be overly concerned as to what they say or suggest, or what they leave unsaid.” To Murray, Felsen notes, the Black Sailor even in a lowly position on the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn was a success.

One of the first Black people to appear in a monument was a young Black girl in the monument dedicated to Henry Ward Beecher, brother to author Harriet Beecher Stowe, a well-known abolitionist and a charismatic pastor of the Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn. The statue now stands at Cadman Plaza in Brooklyn, and the young Black girl is thought to be Rose Ward, a slave who Beecher freed from the pulpit through a dramatic “reverse slave auction.”

Some statues received mixed reviews from an artistic point of view but the sentiment surrounding these statues was (and still is) clearly celebratory. The statue to Arthur Ashe, Soul in Flight (2000) at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Queens, for example, was decried by many when it was first unveiled as many thought it did not look like Ashe. Felsen noted also that the artist never wanted it to look like Ashe. It was meant to be an allegorical figure. Also folks were arguably more upset about him being naked. Eventually. however, it became accepted by the public for its larger significance. His wife was quoted as saying, “I am pleased that the figure celebrates the life of an African-American man in a park that serves an incredible mosaic of ethnic groups in this great city.”

The monument to baseball hall-of-famer Jackie Robinson, in New York City’s Jackie Robinson Park (Harlem, 1981), was the first public statue to honor an athlete of any race. But perhaps even more important and poignant is the Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese Monument at the Brooklyn Cyclones Stadium. Felsen writes, this monument is dedicated to the moment when “Pee Wee Reese, the Dodger captain and shortstop, came over to Robinson, who was receiving a torrent of abuse, and put his arm around his shoulders and silenced the crowd.” Robinson, like Ashe, was an activist and worked tirelessly in support of Black civil rights by demonstrating and fundraising. These statues not only support the Black communities of today, but also remind us of the incredible courage and strength Black leaders must have had to endure the resistance and rejection in their daily lives.

So, rather than contribute to the monument controversy surrounding the Confederate statues, particularly after the killing of George Floyd, Felsen’s book focuses on how these Black monuments celebrate important people and moments in Black life in America. Yes, the statues depict the harsh reality of slavery and the painful effort that Black Americans have exerted to address inequities and racial prejudice, but these statues also create touchstones for the Black community and for those who join with them in supporting equal rights in America.

The neighbors and friends of Ralph Ellison, the author of the Invisible Man, dedicated a monument at 150th Street and Riverside Park. Ellison was a famous writer who also taught American and Russian literature at Bard College and was the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities at NYU. The monument brilliantly illustrates his feelings of invisibility with a 15 foot, 5000 pound statue that is a cutout of Ellison’s profile along with the author’s famous quote: “I am an invisible man….I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” The statue is a recognition not only to his contributions to society as an author and teacher but also as a demonstration of their love for their friend, colleague and neighbor.

There are many stories in this very worthwhile and readable book which we have not included here but that are informative and in-depth but not too long. You don’t have to read the book all in one go to enjoy it, and it can serve as a guide and a reference book. Whether you organize a walking tour with friends or make individual sojourns, these monuments are well worth the visit. The book is also about the celebration of community not only for Black people, but all people. David Felsen says, “it’s especially important [at this moment in history] to recognize the unique experience of being Black in America. I’m also hoping that people will use the book to either visit a part of the city they’ve never been to before or to maybe see their own neighborhood in a new light.” Whether you live in New York City, Chicago or New Orleans or Los Angeles, we hope that you will take time to note the meaning of public art in your neighborhood.

By Victoria Larson, publisher Side of Culture

Featured Photo: Marquis de Lafayette Memorial, Prospect Park. Photo by David Jacobs

Wonderful article about such an important and interesting book ! I’m reading it right now and keep my eyes open when in NYC and Brooklyn to see them in person. Congratulations to David for a great success!

thank you Lucille!