In Philadelphia, exploring beyond Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell offers fresh perspectives on the city’s formative role during America’s early years. Ten miles northwest of Center City in the Germantown neighborhood, Cliveden and other sites present important stories for the local community and nation. Owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation since 1972, Cliveden was the longtime home of the Chew family and is recognized for its key role in the Battle of Germantown during the American Revolution. Another aspect of the family’s history has emerged more fully since 2009 through the Chew family’s records: ownership of plantations and enslaved people. Today Cliveden illuminates the lives of the people who worked for the Chews as well as the experiences of family members, providing opportunities for discussion and dialogue.

From Family Home to Battleground to National Trust Site

The Chew family arrived in Jamestown in 1622, and Benjamin Chew (1722–1810) achieved social prominence in Philadelphia through his work for the Penn family. A lawyer, he became Chief Justice of the Province of Pennsylvania before the Revolution. Cliveden was completed in 1767 by German craftspeople as the wealthy Chew family’s rural summer refuge from heat and yellow fever. The handsome gabled, stone house uses local Wissahickon schist and shows the symmetry of Georgian architecture.

The house’s sturdiness was challenged during the Battle of Germantown on October 4, 1777, when the British occupiers of Philadelphia repulsed George Washington’s assault; 11,000 soldiers were engaged. More than a hundred British soldiers sheltered in Cliveden, inflicting damage on the American troops. Washington lost the battle, but the colonists’ fighting spirit impressed potential European allies. After the war, Benjamin Chew (a fence-sitter during the conflict) returned to Cliveden; he later offered advice during the Constitutional Convention. The family’s business interests in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland included nine tobacco and wheat plantations that used enslaved people, and some enslaved people worked at Cliveden alongside free Black people and indentured servants.

The family’s fortunes changed over the years, but Chews remained Cliveden’s proud owners for seven generations as Germantown developed around it. In the 1870s, the time of Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition and the Colonial Revival movement, the family burnished its role during the Revolution. In 1966, Cliveden became a National Historic Landmark. Eventually, living in the house raised financial and security issues, and in 1972, Samuel Chew III transferred its ownership to the National Trust. The house opened to the public in 1973 and now has about 11,000 visitors annually.

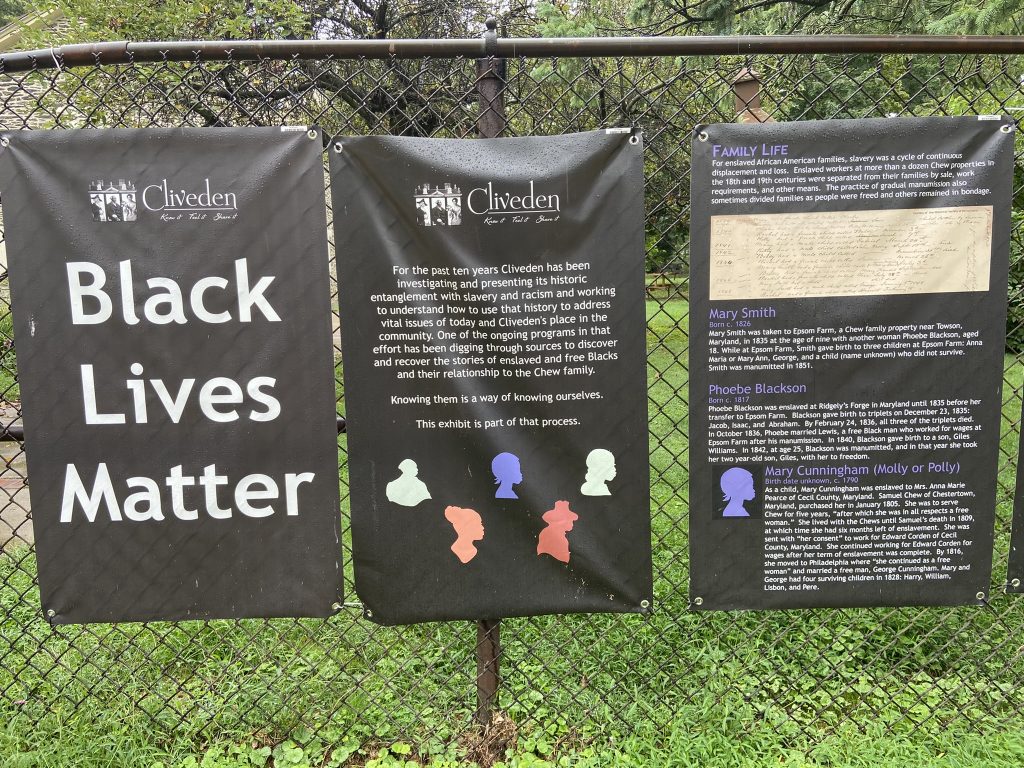

In 1982, the Chew family donated an astounding trove of documents dating to the 17th century—more than 200,000, or 288 linear feet—to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which opened the archived documents to the public in 2009. Information from research into the Chew Family Papers continues to reshape interpretation at Cliveden to be inclusive of everyone involved with the site.

Visiting Cliveden and Germantown

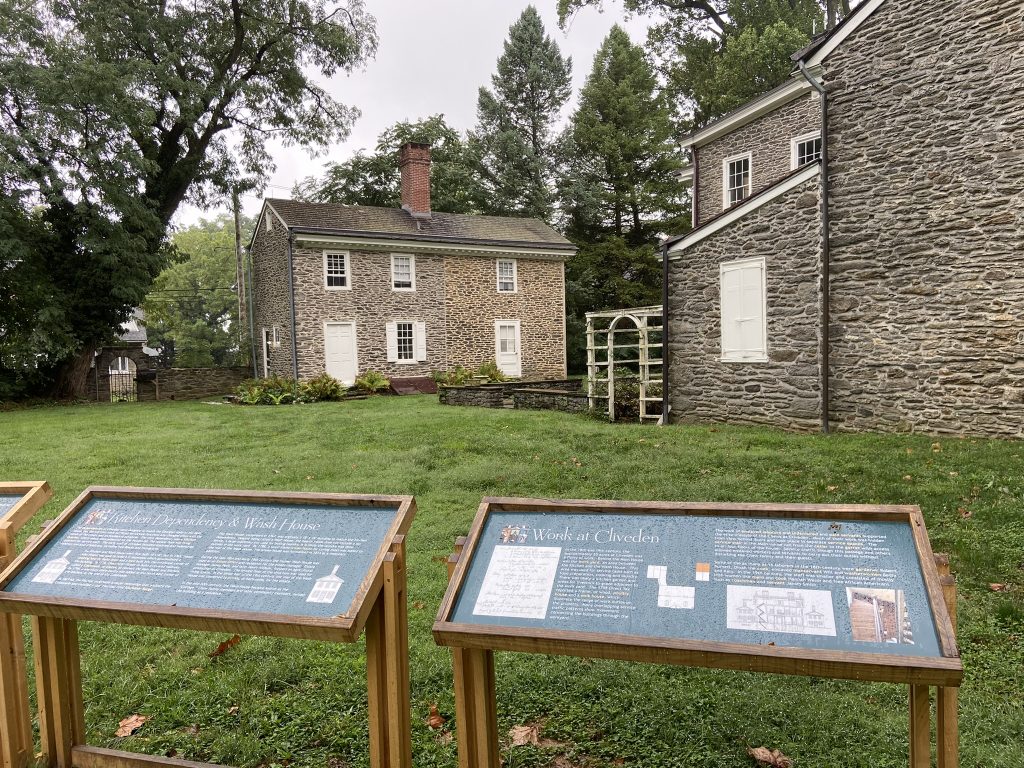

Today Germantown is an urban, diverse, predominantly Black community. Cliveden occupied 60 acres at its largest; today the 5.5-acre grounds fill a leafy city block bordered by busy Germantown Avenue. The house looks much the same as when it was built, though a connector was added between it and the original, separate kitchen building. Another structure (not open to the public) was a wash house.

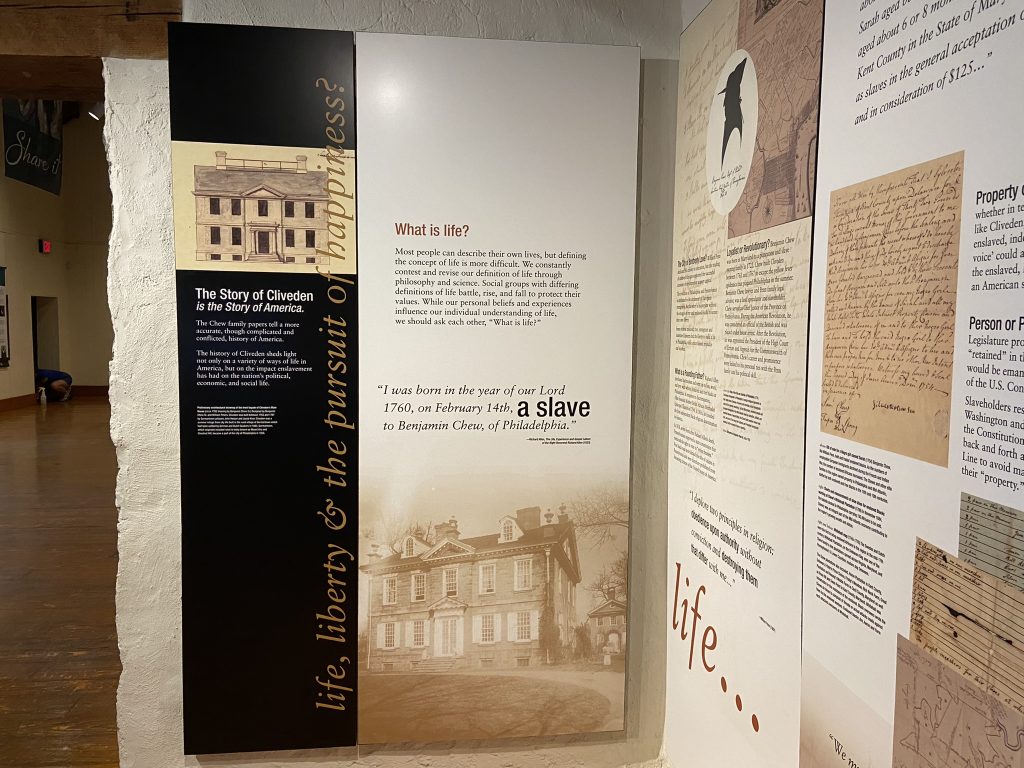

Visits begin in the Carriage House, an information center with exhibits; house tours (check website for open days, months, and options; book in advance if possible) begin here. Installed in the Carriage House in 2012, “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness?” uses Cliveden’s story to discuss the paradox of American freedom: The Declaration of Independence did not apply equally to all people. Visitors should allow time before a tour to read the information-packed panels, which explore, among other topics, the house’s history, the family’s business dealings, and the lives of people associated with the Chews. Richard Allen was one such person, born into slavery in 1760 on a Delaware property owned by Benjamin Chew. Chew sold Allen and his family to another plantation, and Allen eventually bought his freedom and became the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Exhibits also present information about slavery in the North as well as Germantown’s role in the Underground Railroad.

Besides their papers, the Chew family preserved much of its furniture and furnishings, and many items in the elegant house are original, from chairs, mirrors, and cabinets to portraits and paintings. Visitors see two floors of the house on a tour, including a parlor, dining room, and bedrooms. Also on view are the mint-green 1959 mid-century modern kitchen and the unrestored original kitchen. Tours are flexible, with interpreter-guides providing a basic introduction. Attendees are encouraged to ask questions about what interests them, whether it’s the house’s architecture and furnishings, the Chews, slavery, or American history.

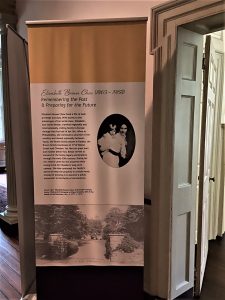

On display in the house since 2020 (but changing for the 2023 tour season, so check website) is “Preserving and Adapting Their World: The Women of Cliveden.” Information boards present the experiences of women of different classes and races who supported Cliveden. The women include Anne Sophia Penn Chew (1805–92), who repaired Cliveden despite financial constraints, and Almira Saunders (1921–2007), who cared for children at Cliveden, cooked, and cleaned.

Cliveden is a member of Historic Germantown, a partnership of 18 historic sites and museums in Northwest Philadelphia. The members collaborate to preserve these community assets and increase their visibility, with the goal of enhancing the area’s economic and cultural development. The partners represent remarkable parts of the city’s heritage: to name a few, Stenton was the home of James Logan, secretary to William Penn; the Quaker-owned Johnson House was a station on the Underground Railroad; and the Germantown White House (part of Independence National Historical Park), President Washington’s home in 1793–94, interprets the experiences of the president and other house residents.

Cliveden and Community

The serene gardens of Cliveden are a serene space open free to the public Thursday to Sunday for strolling and relaxing. Benches and panels with information about the house decorate the tree-shaded grounds. Cliveden also partners with area organizations that sponsor events such as yoga classes and Baby Wordplay events on its grounds.

Cliveden prioritizes being responsive to the local community, as shown by its recent reconsideration of a popular on-site annual event, the October Revolutionary Germantown Festival, which has featured battle reenactments with firearms. Community members questioned whether the event’s format was appropriate at a time when national and local gun violence are a concern. Working with the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, Cliveden undertook dialogue with community members that led to a reorientation of the event in 2022 to enhance its educational value while still including a tactical demonstration. Although the event, scheduled for October 1 this year, was canceled due to inclement weather, the new format can be used in the future.

Begun in 2010, Cliveden Conversations is a program for the public that increases awareness of history and the issues it raises. Topics have included archaeological updates about Cliveden and discoveries from the Chew Family Papers about early Black families. There’s also a wealth of material and links on the website about research relating to Cliveden.

Cliveden is part of History Hunters, a fully subsidized field-trip program for fourth and fifth graders in Philadelphia that involves five Historic Germantown sites. Students become reporters, writing about buildings and artifacts.

Looking ahead, Cliveden hopes to preserve more of its cultural landscape, such as restoring the original kitchen, and to continue expanding its presentation of Cliveden’s world, including the Leni-Lenape people who lived in the area as well as Cliveden’s 20th-century story.

Side Dish

Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee and Books (“Cool People. Dope Books. Great Coffee”) on Germantown’s main drag is the place to take in the local vibe as well as good coffee and a snack, and to browse books focused on Black culture. A 10-minute drive from Germantown leads to Philly’s Manayunk neighborhood, once a mill town. The Couch Tomato, a casual café and bistro, focuses on pizza, salads, and sandwiches using organic local produce and hormone-free meats. SOMO offers hearty brunch options in a lively setting Thursday through Sunday.

Linda Cabasin is a travel editor and writer who covered the globe at Fodor’s before taking up the freelance life. She’s a contributing editor at Fathom. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter at @lcabasin.