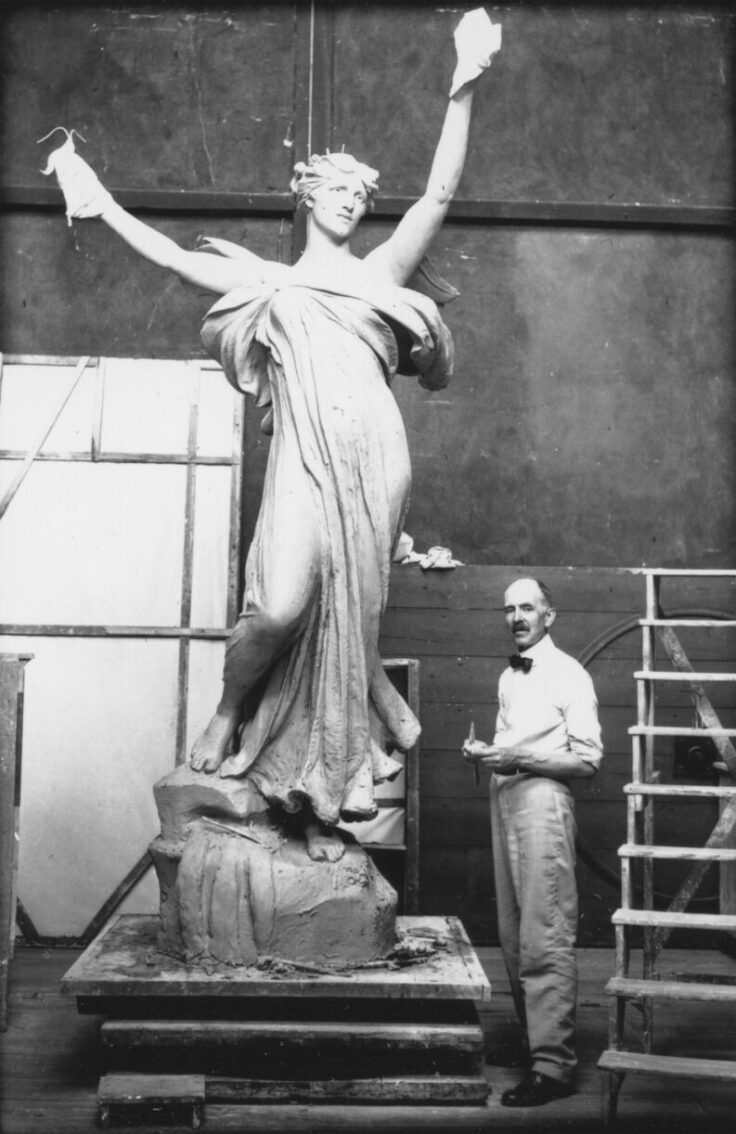

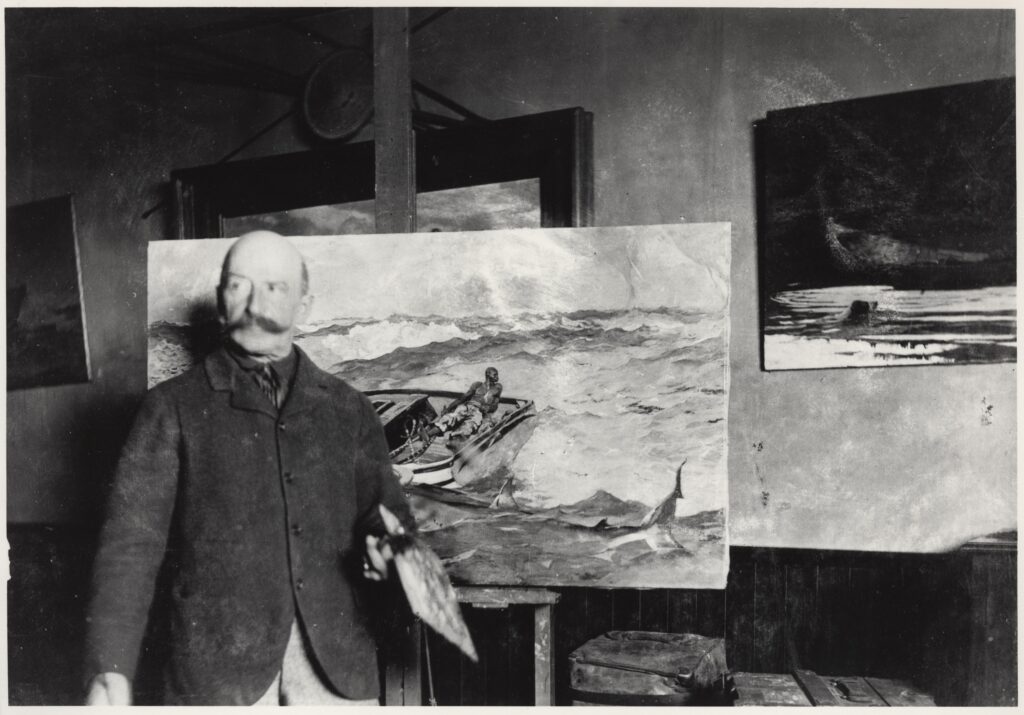

Side of Culture had the good fortune this January to speak with Valerie Balint, Senior Program Manager of the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS), a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and a membership coalition of nearly 50 independent museums that were the homes and working studios of three centuries of American visual artists, such as painters Winslow Homer, Andrew Wyeth, conceptualist David Ireland and artists Suzy Frelinghuysen and George Morris. Side of Culture also has featured a few others, including Olana, the home of artist Frederic Church; Chesterwood, the home of sculptor Daniel Chester French, The Thomas Cole House and the home of the artist enclave fostered by Florence Griswold.

Historic Artists Homes and Studios was created in 1999 to empower a dynamic network of artists’ living and work spaces (now preserved as historic homes and art museums) through mentoring, public outreach, critical peer-to-peer exchange, and networking to help create meaningful personal experiences at authentic creative places of American artists.

With her wealth of experience, Balint is well positioned to speak to the depth and breadth of the HAHS. She is the author of the newly released Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (Princeton Architectural Press, June 2020. And, prior to heading HAHS, beginning in spring 2017, Ms. Balint served for seventeen years on the curatorial staff at Frederic Church’s Olana (also a HAHS site), most recently as Interim Director of Collections and Research. She was co-organizer and co-curator of Olana’s annual exhibitions and accompanying publications.

She is a frequent lecturer and writer on preserved artists’ spaces, Frederic Church, the Hudson River School, and American art and social history of the mid-19th and early 20th century. She is co-author of Glories of the Hudson: Frederic Church’s Views from Olana (Cornell Press, 2009). Her previous work also includes curatorial positions at Chesterwood and the Frelinghuysen Morris House & Studio (also HAHS sites). She served as the New York State Coordinator of “Save Outdoor Sculpture,” a program of the Smithsonian American Art Museum to document all public sculpture in the United States. She is a longtime advocate for recognizing the value of artists’ homes and public art within the greater context of cultural history.

SofC: For those who love to see artworks at major museums, what is different about seeing art in the homes and studios of these artists?

VB: These houses and studios are complementary, yet distinctly different than going to a major museum. In these preserved spaces that were once homes and studios, visitors see all the things that went into making a work of art, both the mental inspiration and the physical process. When one contemplates a work of art in the museum, visitors focus on the object itself, not the story behind it, which can be gained by visiting where it was created.

I like to think that even seasoned devotees of any artist will discover new things when they visit the place where that artist lived and worked. Most sites have significant artwork created by the artist(s) who lived there, enabling visitors to see connections between the art and the place, as well as extensive archival holdings and specialized libraries, making them important resources for art historians, students, and professionals in other disciplines. Also, for less seasoned museum goers, artists become more accessible and perhaps better understood and appreciated by engaging with their biographical stories and their art through this type of immersive experience.

SoC: Are there common themes that emerge when experiencing these homes and sites?

Every one of these sites is imbued with a sense of the power of place – of being able to immerse oneself in the environment that fueled an artist’s creativity. I have been to dozens of these places around the country, and every one fills me with the same sense of awe and wonder – each time I visit.

In these preserved spaces, you see all the aspects of their life and work, and how those come together. The choices they made about where and how they chose to live say something about who they were, how they evolved as artists over time, and how that is expressed in their personal environments. Often, the artist spent more time designing and creating their homes and studios than on any single painting or sculpture in their career and so these sites are deeply personal.

Regardless of style of location, every artist needs to be inspired by their environment, while simultaneously molding that environment to be an extension of their creative process.

Also, the structures and surrounding landscapes were often substantially designed by the artists, illuminating other explorations of artistic practice – these sites and museums are often works of art in themselves.

Lastly, many of these sites serve as inspiration for living artists. So, a visitor can experience the historic site while also engaging with an exhibit, work of art, or program by a contemporary artist. That bridge from the past to the present is something unique these sites have to offer.

SoC: How does a site become a member of HAHS?

VB: Each year, prospective sites are invited to apply to join HAHS, and their applications are peer-reviewed. Each member site must be open for visitation, operate as a non-profit, be historic, and be dedicated to preserving and interpreting the places where art was made. HAHS does not currently include living artists’ studios, but we are frequently in discussions with the living artists who are exploring the possibility of preserving their site as a future museum. We are also constantly in dialogue with preserved artists homes throughout the country and working to bring in new members. Currently the network includes sites that represent three centuries of art in this country – all visual artists, including painters, sculptors, photographers, ceramists, textile makers and furniture designers.

Balint continued: Our membership right now consists of 48 sites in 22 states with eight new sites in the process of applying right now. Announcement of these new sites will happen this spring – and with that, we will also add an additional three new states who then will have sites represented in our program – Georgia, Tennessee, and Washington. We are very committed to seeking more sites of under-represented communities, such as African American, LatinX, LGBTQ+, and Indigenous artists – and this will be a focus over the next few years. Among those new members we will welcome to the program this year, are sites dedicated to the legacies of two African American artists, three women artists, three self-taught artists, and two artists identifying as LGBTQ+. Many members are small, private non-profit entities, although some are owned by larger art museums, educational institutions, or government agencies.

SoC: You have written and created a beautiful and informative guidebook for HAHS, can you tell us about this?

VB: As the author, my goal was to create something that could capture the imagination of those who are just beginning to learn about our nation’s rich artistic legacy, while also providing new discoveries for those well versed in certain artists or sites. We conceived and planned the guidebook as part of the celebratory 20th anniversary of the program. It was underwritten, as the program currently is, by a generous grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, with additional support from the Wyeth Foundation for American Art. We deliberately set out to create a true guidebook, that you could throw in your purse or backpack, which we hoped would entice people to visit these amazing sites, but that could also serve the armchair traveler. We hope that each issue will become dog-eared as people mark off the places they wish to go!

SoC: What is the impact of HAHS on the local economies? Do they spur local development and business?

VB: The popularity of these sites continues to rise and the interest in preserving artist sites is also increasing. Collectively, HAHS sites draw more than 1 million visitors each year. Expanded virtual programming, resulting from the pandemic has increased the program’s and our member sites’ reach even further, as we engage audiences in new ways.

The sites are important economic engines as each individual site serves as a cultural anchor in its respective community – and, like a pebble dropped in a pond, a site’s impact radiates out into larger circles that support local businesses and jobs, and even contemporary creatives. Many of these sites also directly engage with living artists through exhibitions, art-making workshops, and artist-in-residence programs. Our member sites often exist in communities that have been a draw for artists over many decades – or even centuries – so there is a deeply imbedded connection between an artist whose legacy is now preserved at a public museum, and those artists creating in that same community today. In fact, many living artists are often directly inspired by these historical artists – and the places where they lived and worked. Staff at these preserved homes and studios also actively create programming that links directly back to the fundamental beliefs and interests of the artist whose legacy has been preserved at their museum, while also connecting to issues that are pertinent today. For example, the Thomas Cole site, in Catskill, New York, is committed to creating programs centered around sustainability and other environmental topics. Thomas Cole himself was an ardent naturalist and is considered by some scholars today, a proto environmentalist. Even though Cole lived more than 150 years ago, his concern for the environment is still highly relevant today.

At HAHS, we seek to amplify all the great work of our member sites, while also drawing attention to these sites more broadly in the public consciousness. We are the only organization in the nation that focuses on promoting these types of specific – and may I say, simply amazing – types of sites.

We support our members by connecting them to one another, as well as to other experts throughout the world. Through the sharing of ideas and innovative approaches to challenges all sites face, we hope to offer expertise and models of best practices that can promote and recognize excellence. We focus on bringing our members together for professional dialogue; expanding that conversation to also include others in the fields of art, history, and preservation. But we also actively work to bring these singular properties to the attention of the public at large – so many people love art, travel, and learning about our nation’s history, but are unaware that the spaces of many of our most famous artists have been preserved and can be visited. And of course, there are other artists in the network who are not as famous, as say, Georgia O’Keeffe, whose sites are just waiting to be discovered and enjoyed. So – to get that word out we have a website, ongoing e-newsletter, and other materials to educate people about these inspiring sites – including the book we published in 2020.

In 2021, HAHS launched its first series of virtual public programming, and will expand these offerings in 2022. To keep up to date on HAHS initiatives, and our member sites, we suggest you sign up for our e-newsletter through the home page of our website – artistshomes.org, or follow us on social media.

I am so proud of HAHS’ role as a thought leader in elevating preserved sites of visual artists, and as the only national network dedicated to telling a site-specific story of our nation’s rich and varied art history. As part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a national leader in protecting places throughout the country, HAHS is uniquely poised to serve as an international model and benchmark for this type of advocacy work relative to artists’ spaces. I hope your readers will stay tuned as we continue to grow and offer more artists and sites every year, for them to explore.

As told to Victoria Larson by Valerie Balint

Top photo: William Chadwick Studio, Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, CT Photograph Jeff Yardis, Courtesy Florence Griswold Museum