Tucked away on Mason Neck peninsula and just 10 miles south of Mount Vernon, Gunston Hall tells the story of George Mason (1725–1792), the Virginia planter and lawmaker whose ideas and writings influenced American political thought and documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution’s Bill of Rights. Visitors to this relatively less-known but notable 18th-century mansion and museum explore Mason’s life and legacy and also learn about the enslaved people, indentured servants, and tenant farmers who lived or worked there. Its mission includes ongoing historical and archaeological research so that Mason’s and Gunston Hall’s fuller story can be presented in more authentic ways.

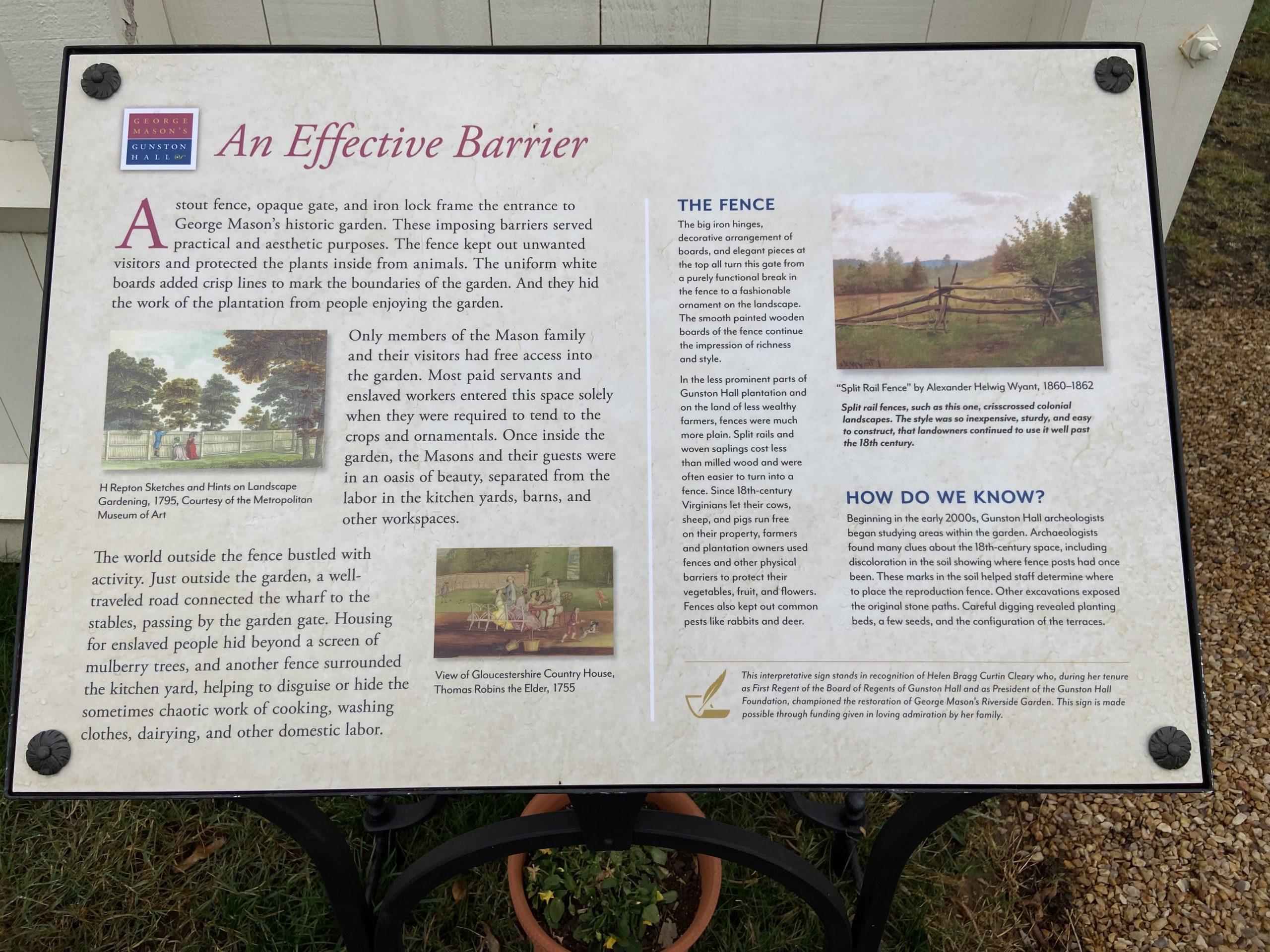

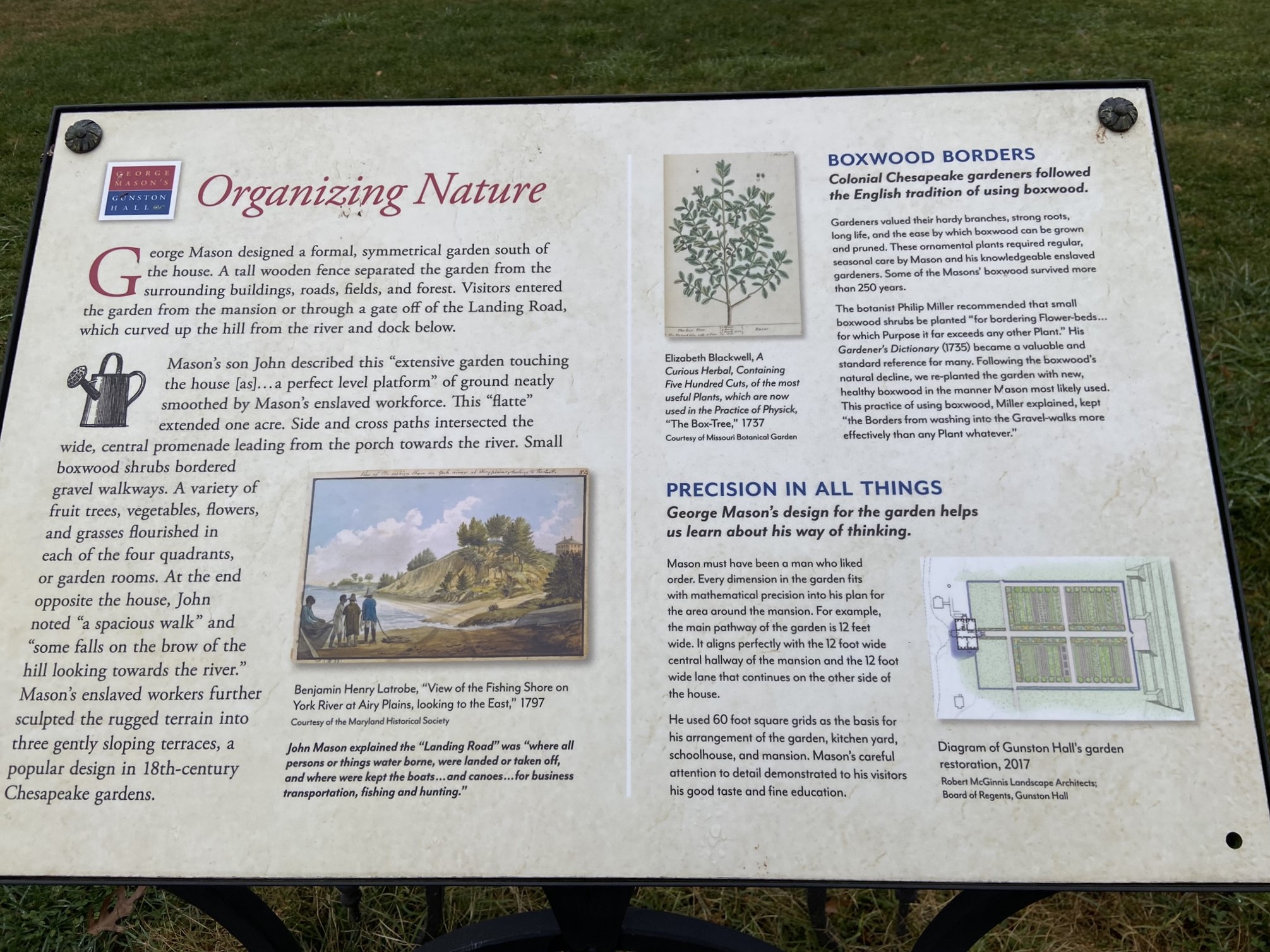

One example of this is the newly restored, stunning 18th-century Riverside Garden, opened in fall 2023. Occupying one acre just behind the house and sited with panoramic views of the landscape and Potomac River, the garden required four decades of research and four years of construction. George Mason designed and managed the garden to be both beautiful and practical: the walled and gated, symmetrical space with its straight pathways and tidy quadrants provided vegetables and fruits for the family and was also a place for relaxing. To create the original space, enslaved people leveled and reshaped the landscape, a massive undertaking. Another long-term undertaking at Gunston Hall, started in 2023, the East Yard Project seeks to uncover the mostly unknown stories of the enslaved community, connect with descendants of those African Americans, and reconstruct buildings that housed enslaved people as a memorial. As the project proceeds, new interpretive experiences will be added on-site.

The Home and World of George Mason

Born into a prosperous, land-owning Virginia family, George Mason married his first wife, Ann Eilbeck (1734–1773) in 1750. Gunston Hall, a stylish mansion that reflected the couple’s status, was built between 1755 and 1759 as the Masons’ home and the center of a nearly 6,000-acre plantation that grew tobacco, wheat, and other crops. The Masons had 12 children, 9 of whom survived to adulthood.

George Mason was a wealthy planter and businessman, but by the 1760s he was assuming the roles that earned him a place in American history: rebel and revolutionary. Working with George Washington, he was the primary author of the 1774 Fairfax Resolves, which asserted the colonists’ rights. As the American Revolution started, Mason served in the Virginia Convention, drafting a Virginia State Constitution and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. The final version of the Declaration of Rights, adopted on June 12, 1776, called for freedom of the press and religious freedom. Article 1 declared “That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights . . . namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty.” Many founding documents would call for individual freedoms, but this was the first. Later, Mason was active in the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia but was one of three participants present who did not sign the final document. His written objections, including concern for the protection of citizens’ rights, influenced James Madison to introduce the constitutional amendments known as the Bill of Rights. These were adopted in 1791, a year before George Mason died.

Gunston Hall remained privately owned, though it was in poor condition when Louis and Eleanor Hertle purchased it in 1912. Louis and Eleanor, a member of the National Society of The Colonial Dames of America (NSCDA), restored the mansion; fortunately, many original features remained. Louis Hertle, who died in 1949, gifted it to the Commonwealth of Virginia so it could be operated as a museum by Virginia and the NSCDA, with a Board of Regents chosen by the NSCDA. Gunston Hall opened to the public in 1952 and has been accredited by the American Alliance of Museums since 1988.

Visiting Gunston Hall

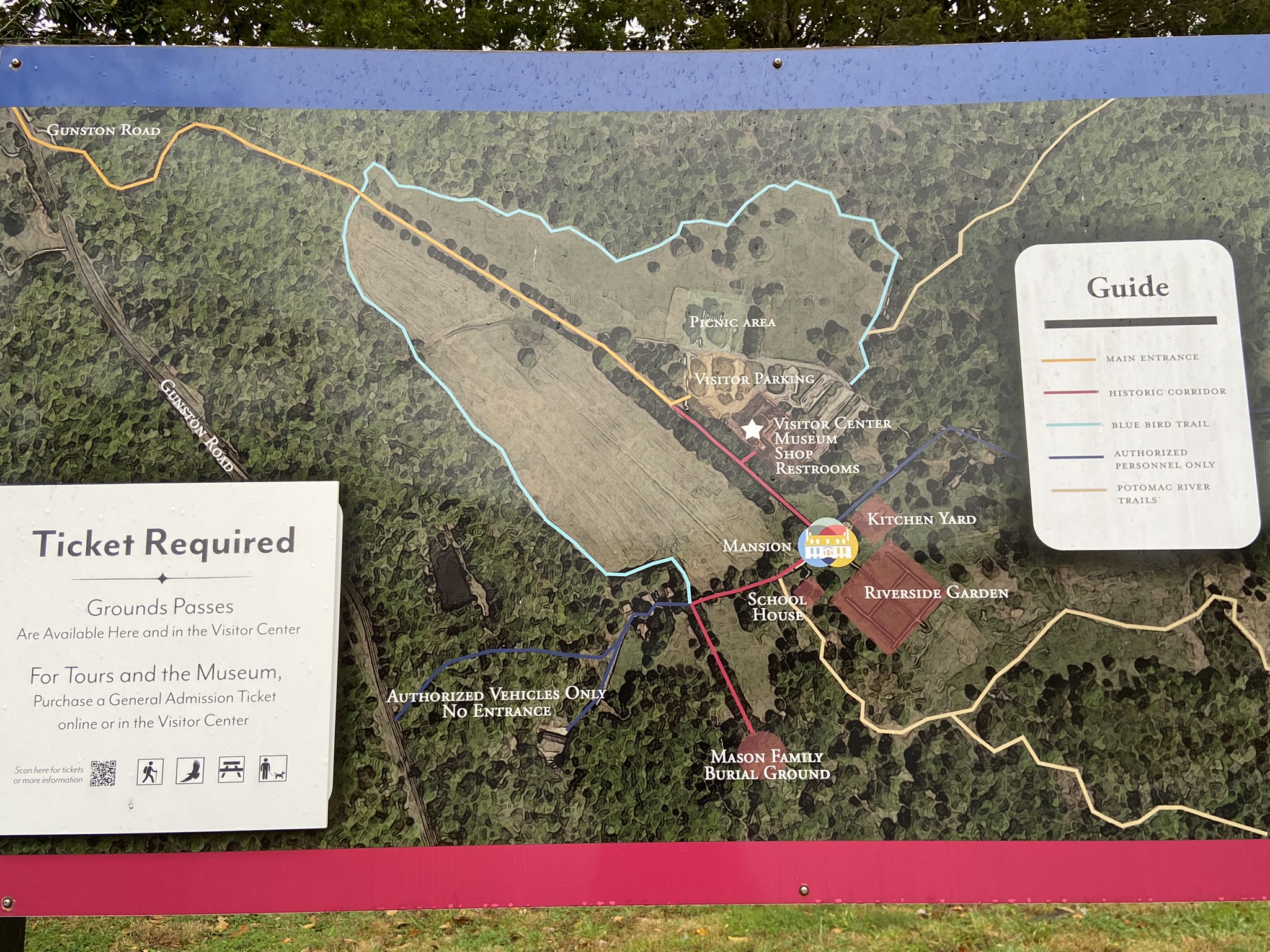

Set on 550 acres 25 miles south of Washington, DC, in Lorton, Gunston Hall includes the historic mansion, a visitor center and museum, the restored Riverside Garden, reconstructed outbuildings, and trails through the wooded property. The mansion’s solid-looking exterior was designed by Mason and built with bricks made by enslaved workers. Mason supervised two indentured servants who created sophisticated interior spaces using a dazzling variety of Rococo elements: carpenter and architect William Buckland, who designed the rooms and would later produce other notable buildings, and master carver William Bernard Sears.

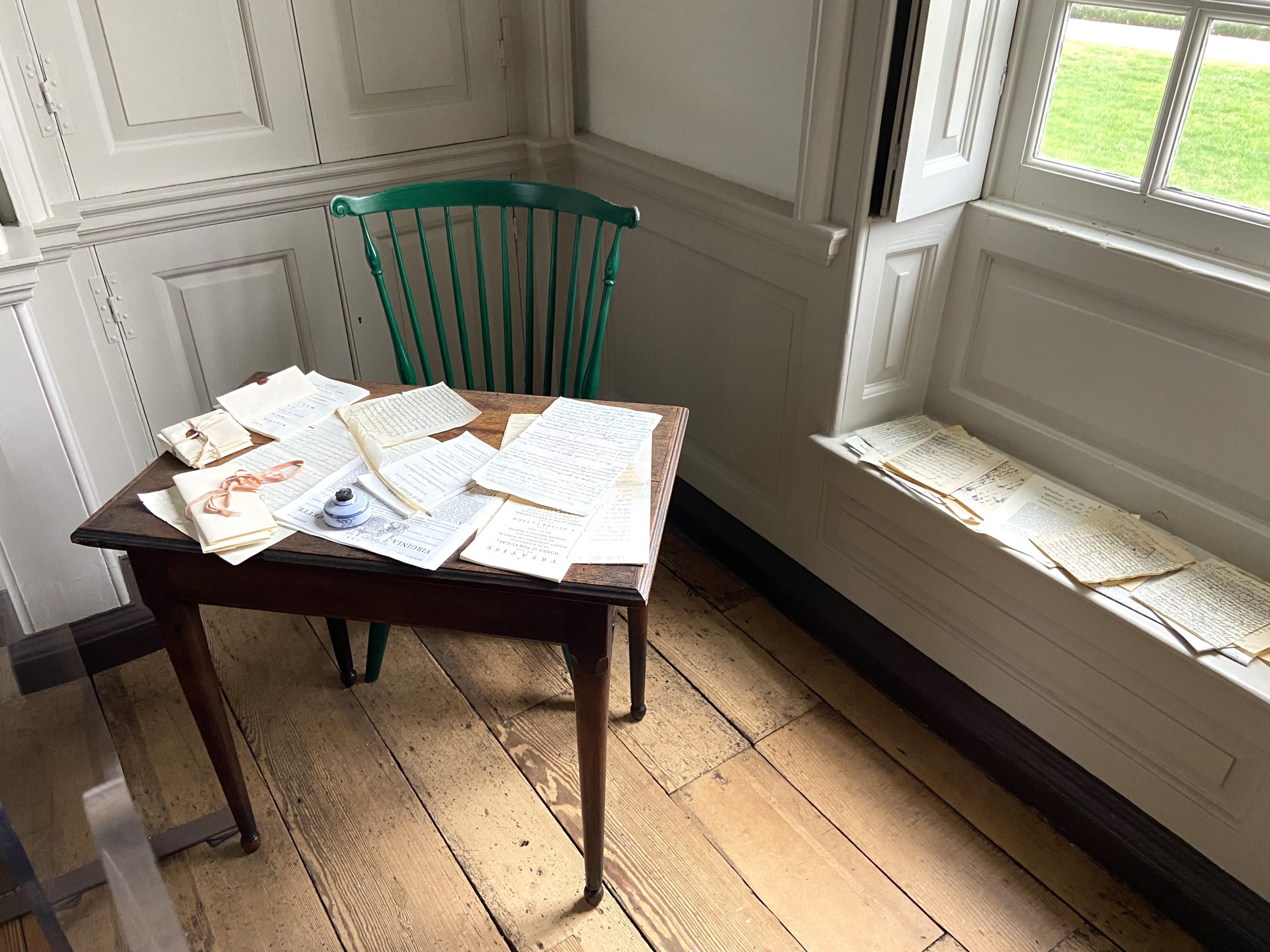

Public rooms conveyed the family’s status, including the wide entry hall with Doric pilasters and an elegant staircase. The most spectacular rooms are the ocher yellow dining room, with rare carvings in what was considered a Chinese style, and the formal Palladian parlor with elaborate moldings and carving. On the other side of the hall are two family rooms: a parlor that served as Mason’s study, with simpler but lovely carving, and the main bedroom, painted a rich emerald green. Most furnishings aren’t original, but period antiques supplement Mason-owned pieces. Upstairs, the house is more utilitarian, with seven plain bedrooms for the children and guests. During tours of the house, questions are encouraged, and some interactive features invite children and all visitors to think about 18th-century life.

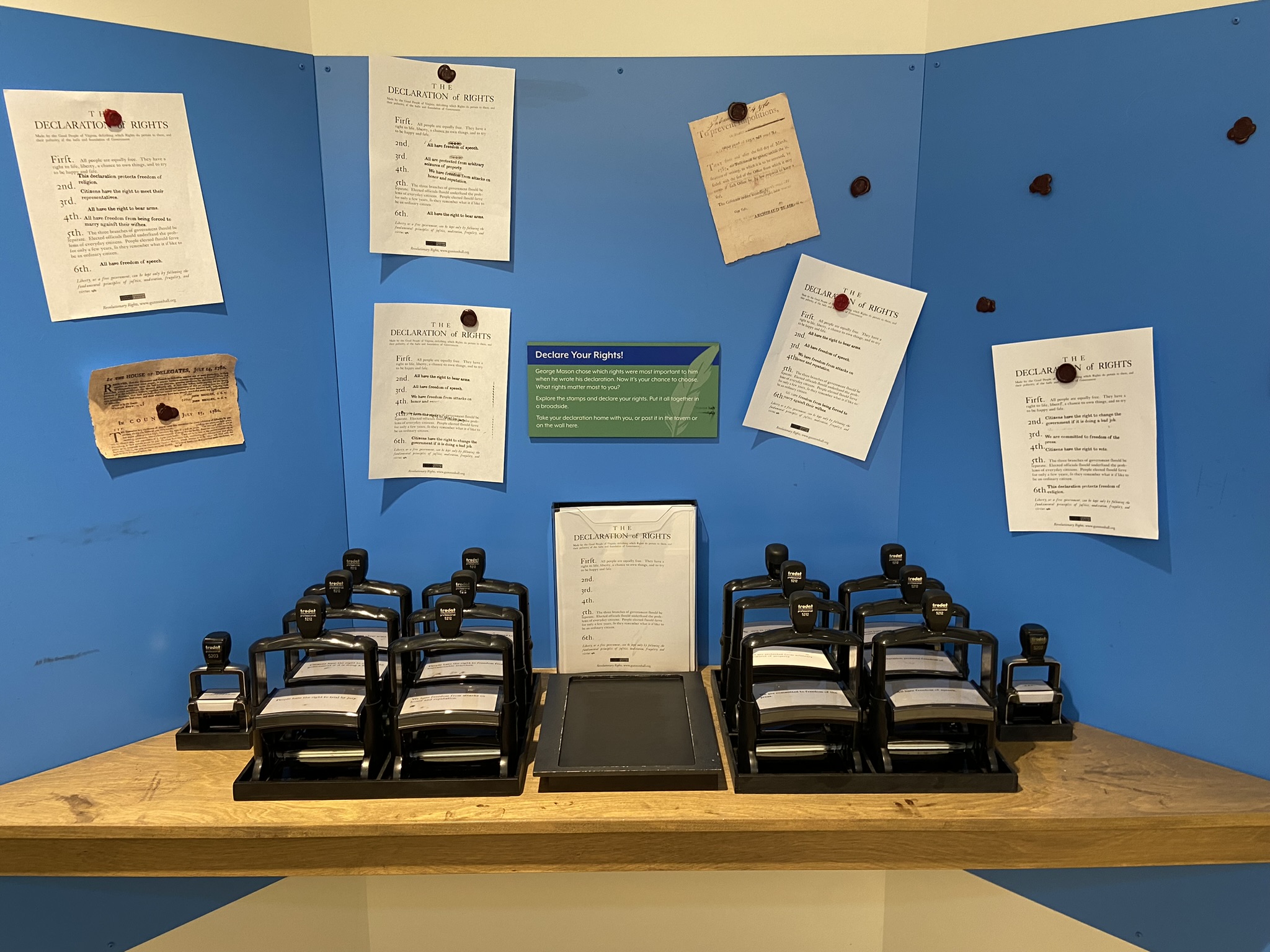

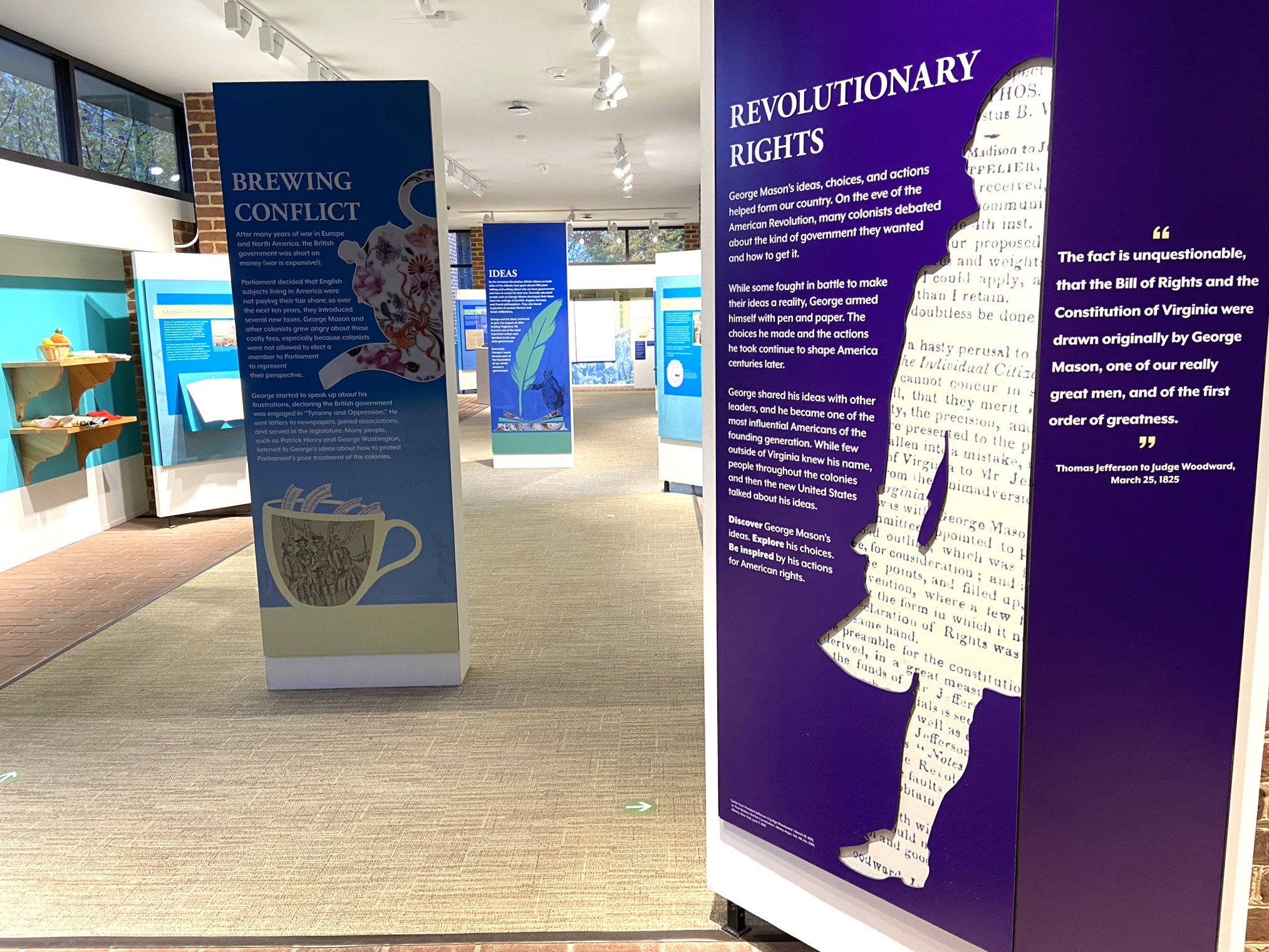

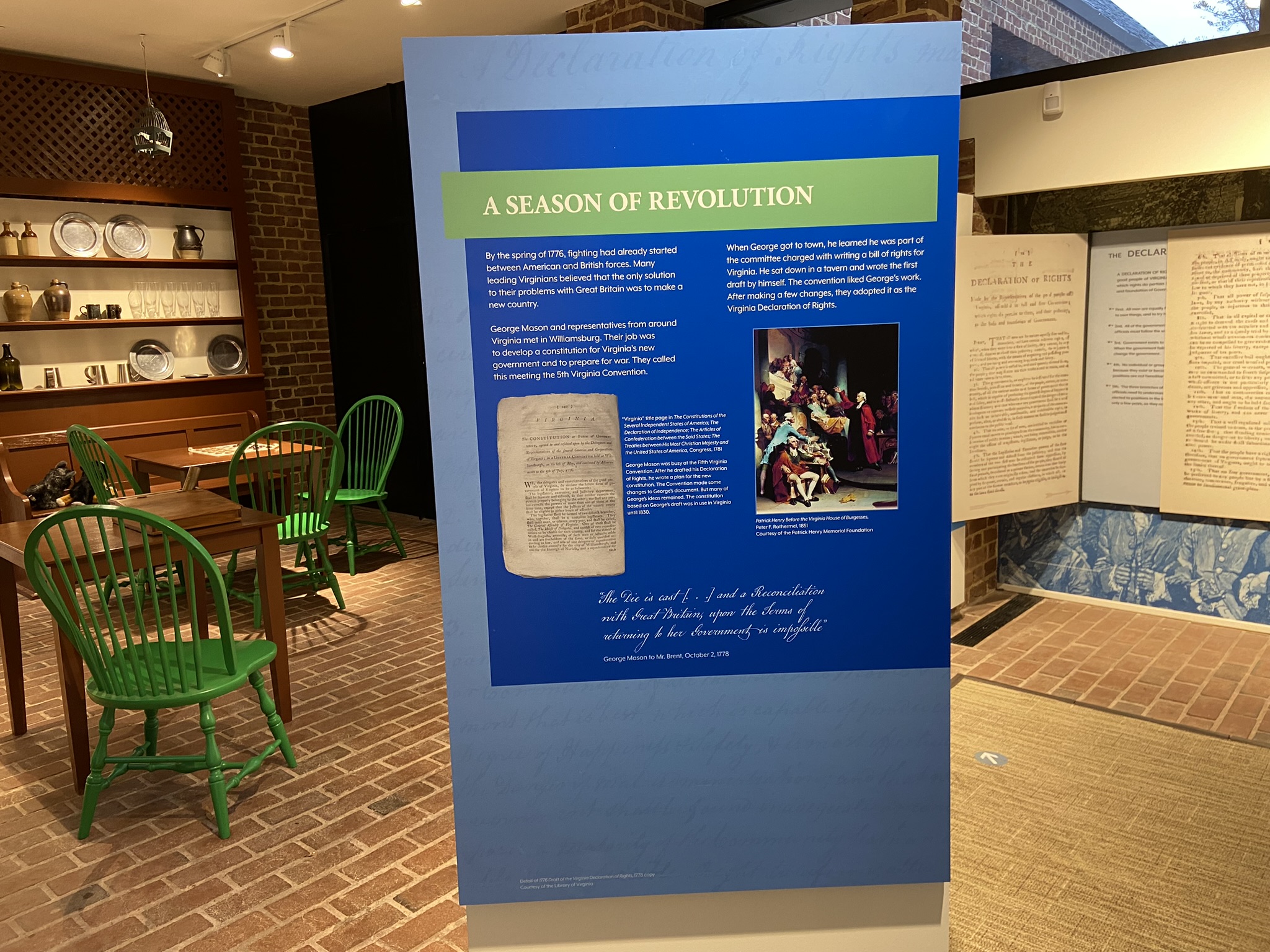

In the visitor center, the permanent, family-friendly “Revolutionary Rights” exhibition examines the issues of Mason’s day and his legacy. Displays present simply and colorfully the story of the colonists’ growing discontent with British rule. A re-created tavern room is a reminder that Mason wrote drafts of the Virginia State Constitution and Virginia Declaration of Rights in Williamsburg’s Raleigh Tavern. In another area, visitors create their own Bill of Rights. Complex issues are presented, though, such as Mason’s disagreements with other delegates at the Constitutional Convention and the reality that the individual rights that concerned Mason weren’t available to everyone in that era. One section assesses Mason’s contradictory position on slavery; he viewed it as a “slow poison” and advocated for ending the international slave trade, but he owned hundreds of people during his lifetime and did not free them.

At the back of the house, steps lead down from the Gothic portico—another example of the house’s architectural distinctiveness—to the newly restored Riverside Garden, which is also a certified butterfly garden. Four illustrated interpretive panels discuss topics such as the garden’s plants and agricultural practices of Mason’s day and who used the garden. (Today much of the produce is given to the Lorton Community Action Center.) Visitors can also sit on the terrace outside the garden and enjoy the view, and see five reconstructed outbuildings, such as the kitchen, laundry, and schoolhouse, to learn more about how the plantation functioned. One great way to end a visit is a walk or hike around the beautiful site, from the Mason family burial ground to the short trails surrounding Gunston Hall.

Programs and Events

Gunston Hall offers resources and programs for everyone from researchers to families. Its extensive reference and rare-book collections and Mason family archives are available for researchers by appointment. Teachers and students can take advantage of themed in-person or remote field trips and topical learning modules and enrichment activities for classrooms. An annual George Mason Essay Contest is open to 4th graders. One popular home-based learning program for adults and kids is History in the Kitchen, which brings history alive in the kitchen through videos and recipes about foods such as apple fritters and chicken pudding. The website’s calendar lists upcoming happenings, from Summer Saturdays programs that explore 18th-century life to events such as the Declaration Day commemoration each June of the anniversary of the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

Side Dish

An excellent choice is to bring a picnic lunch and enjoy the landscape. Seven miles away is Occoquan, a riverside town with a cute historic district and restaurants like the popular, casual Secret Garden Café, which offers alfresco and indoor seating and American favorites with some global touches.

Linda Cabasin is a travel editor and writer who covered the globe at Fodor’s before taking up the freelance life. She explored Gunston Hall last fall while visiting family in Washington, DC. She’s a contributing editor at Fathom. Follow Linda on Instagram at @lcabasin.

WONDERFUL !

Spectacular job displaying dedication, diligence and determination.

APPLAUSE ALL AROUND ~

MK Ruwe