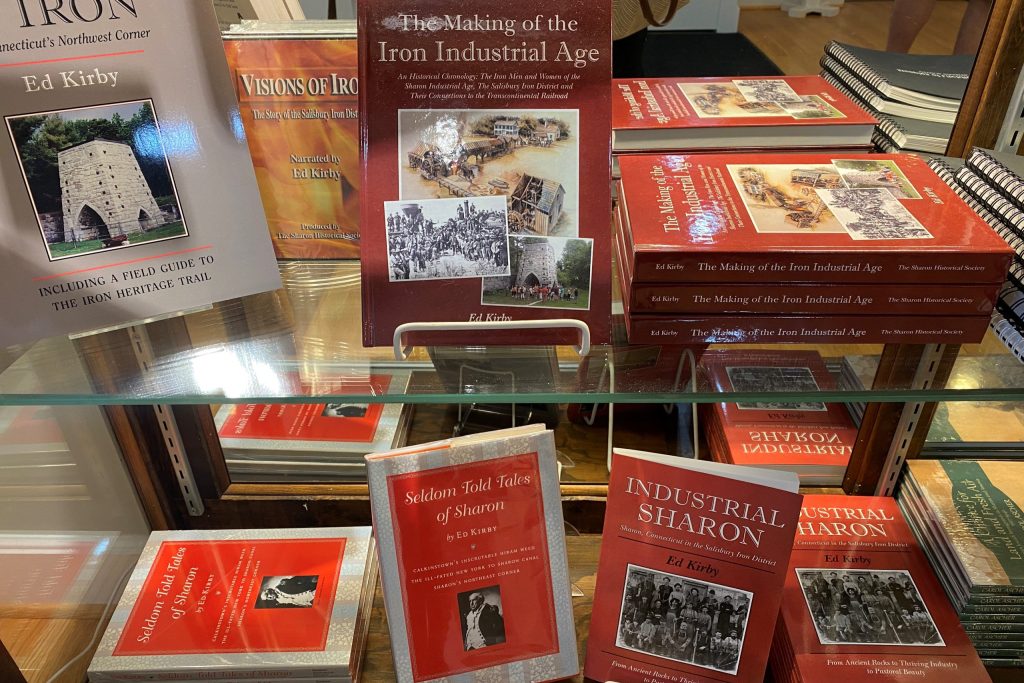

Rather than relegating itself to dusty shelves and shaky internet connections, the Sharon Historical Society & Museum is a quietly strong and vibrant community center on the village green in the peaceful town in Northwest Connecticut. Unique exhibitions, cake auctions, book signings, a library, genealogical and house research and art shows are some of the ways that the Historical Society makes history come alive and the past become meaningful to its residents and visitors.

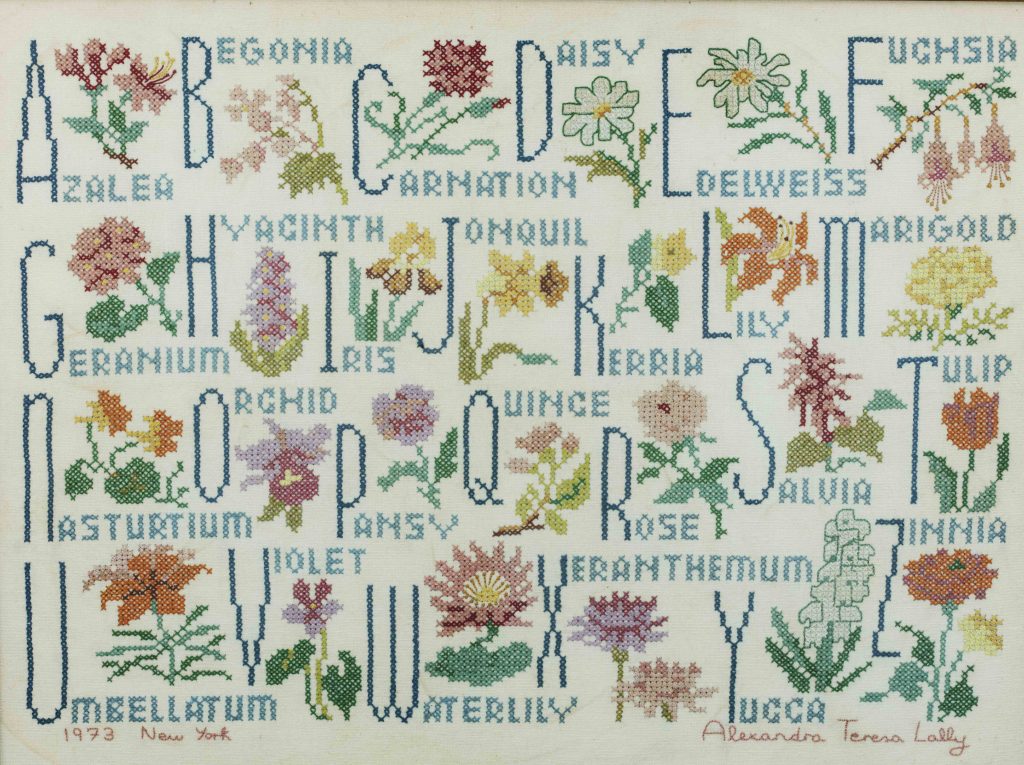

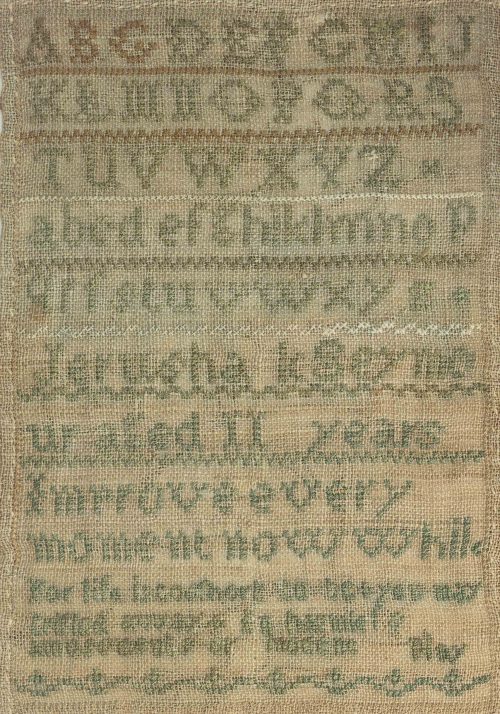

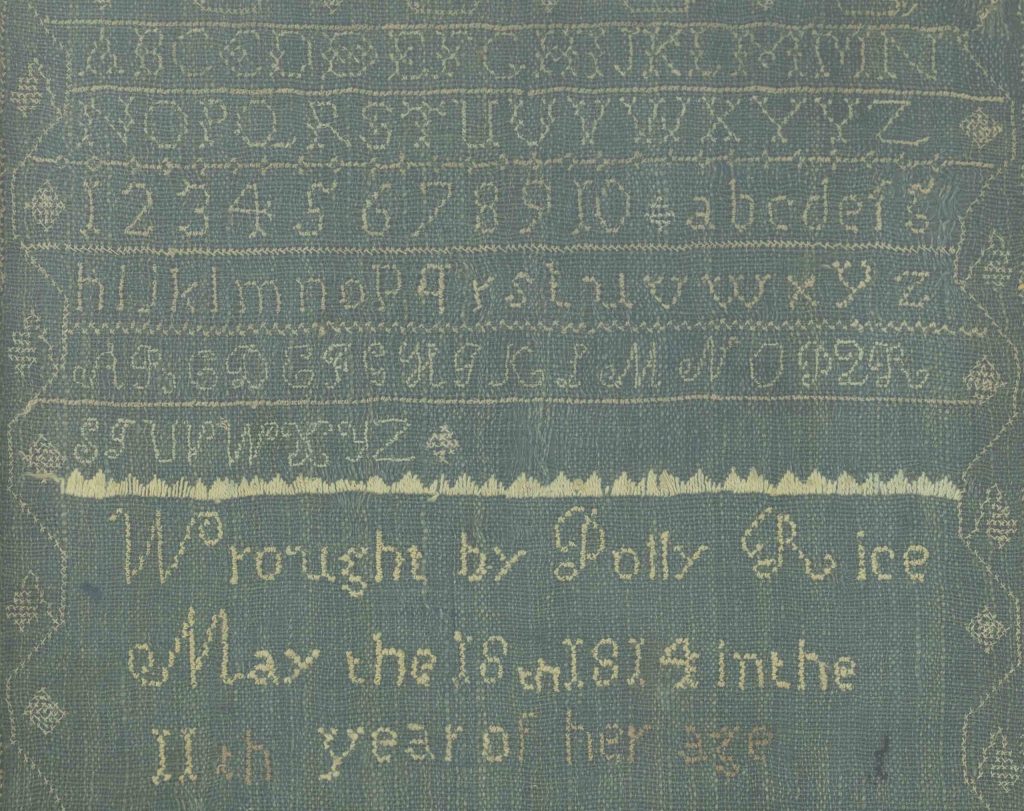

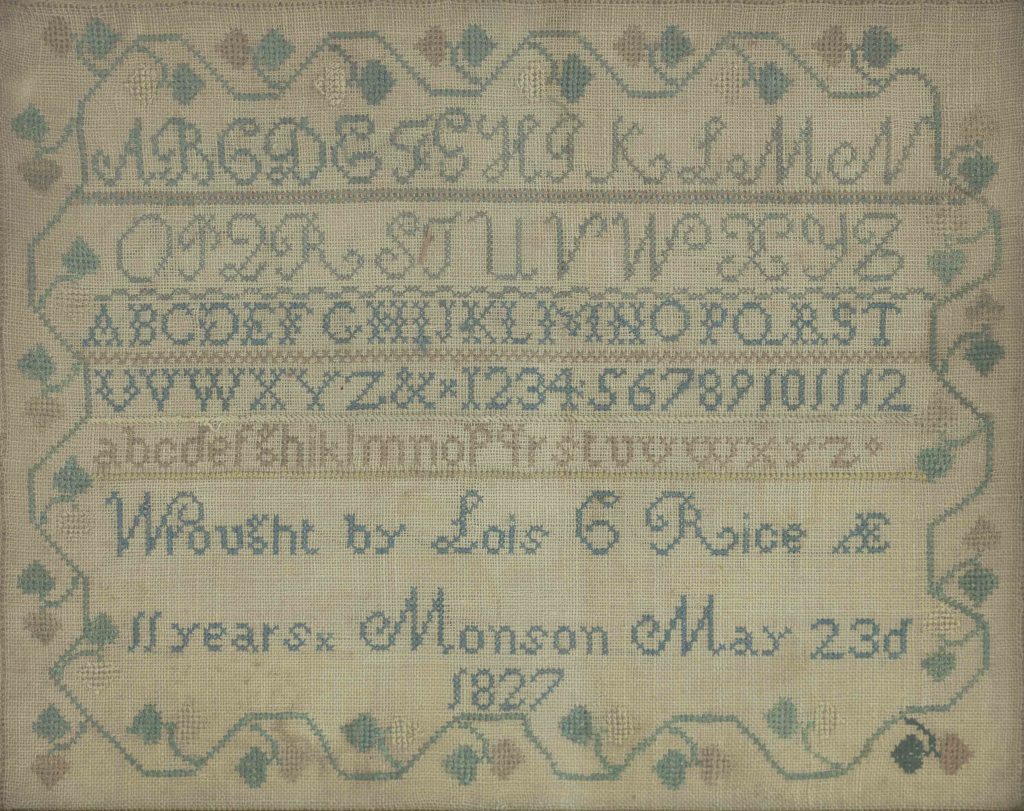

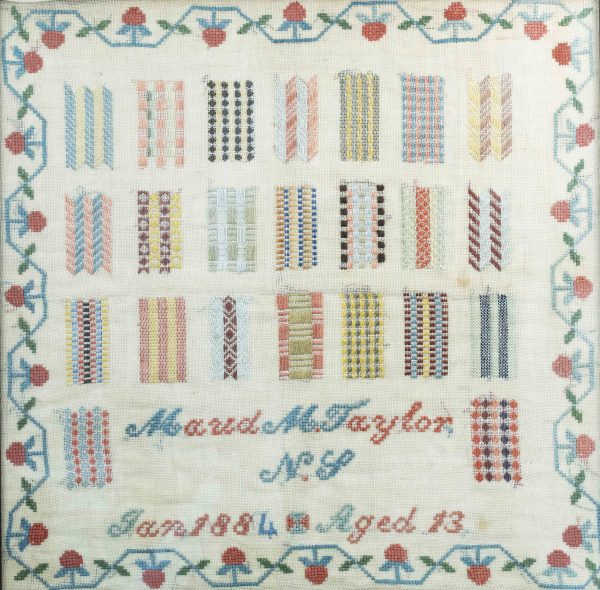

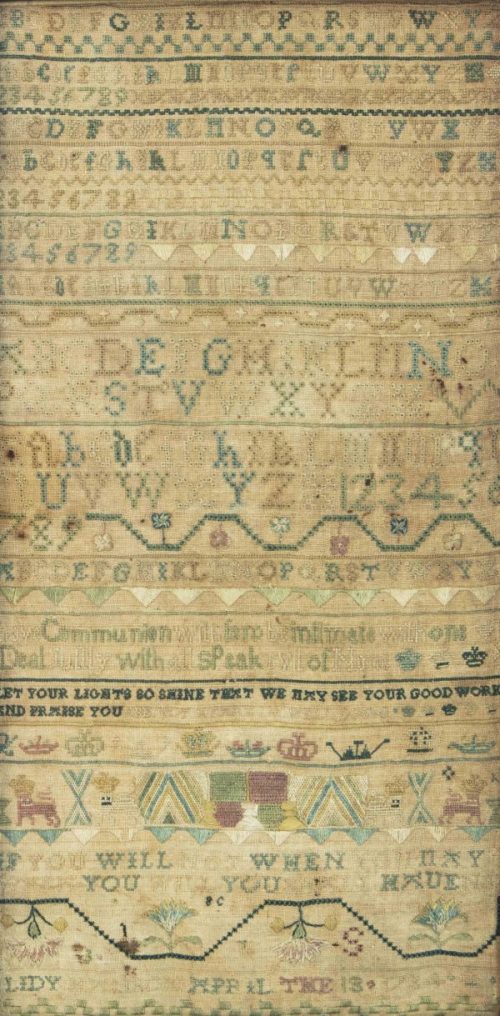

The current exhibition by Sharon resident Alexandra Peters, Sharon Collects: Samplers from the Collection Alexandra Peters, is a telling example of the Society’s thoughtful and insightful approach to making history relevant today. With over 60 works on display from 1692 to 1852, Peters brings to light the role of young girls in America. This was the pre-industrial age when girls and their work were invisible to the outside world but highly valued for their achievements. Almost all of the samplers were completed in elementary or boarding schools by girls typically aged eight to 12.

Christine Beer, Executive Director, noted, “We strive to be a center for community learning and enjoyment by bringing stories of Sharon to life through exhibitions and events. ‘Samplers from the Collection of Alexandra Peters’ is the first installation of what will be an annual ‘Sharon Collects’ exhibition. The purpose of ‘Sharon Collects’ is to highlight how community members are engaging with history to uncover stories we can relate to today.”

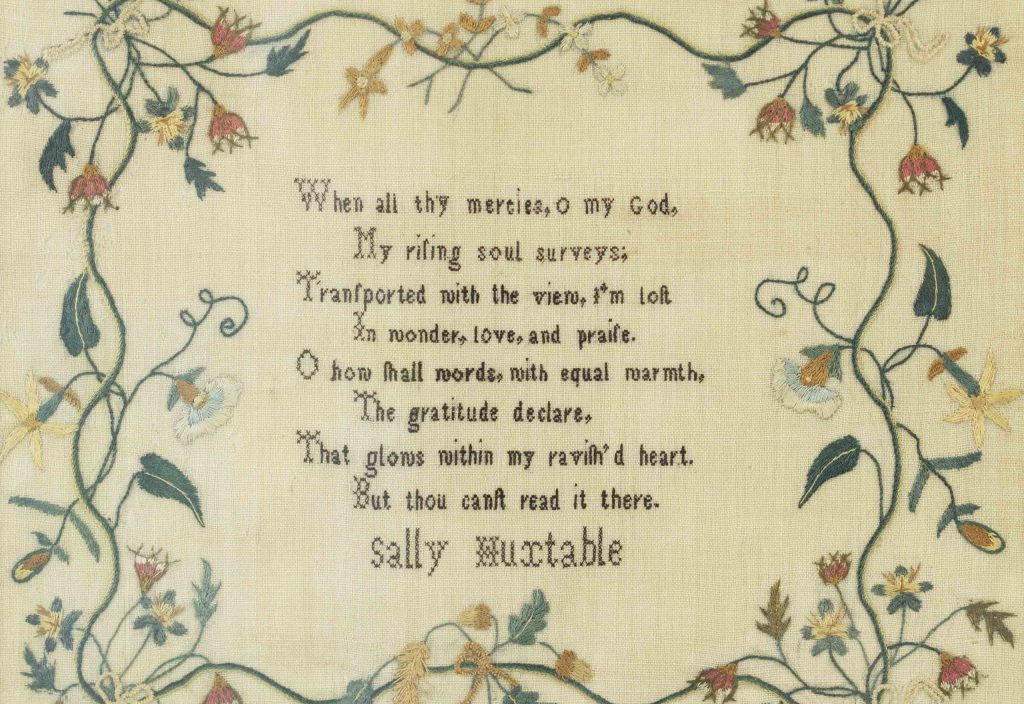

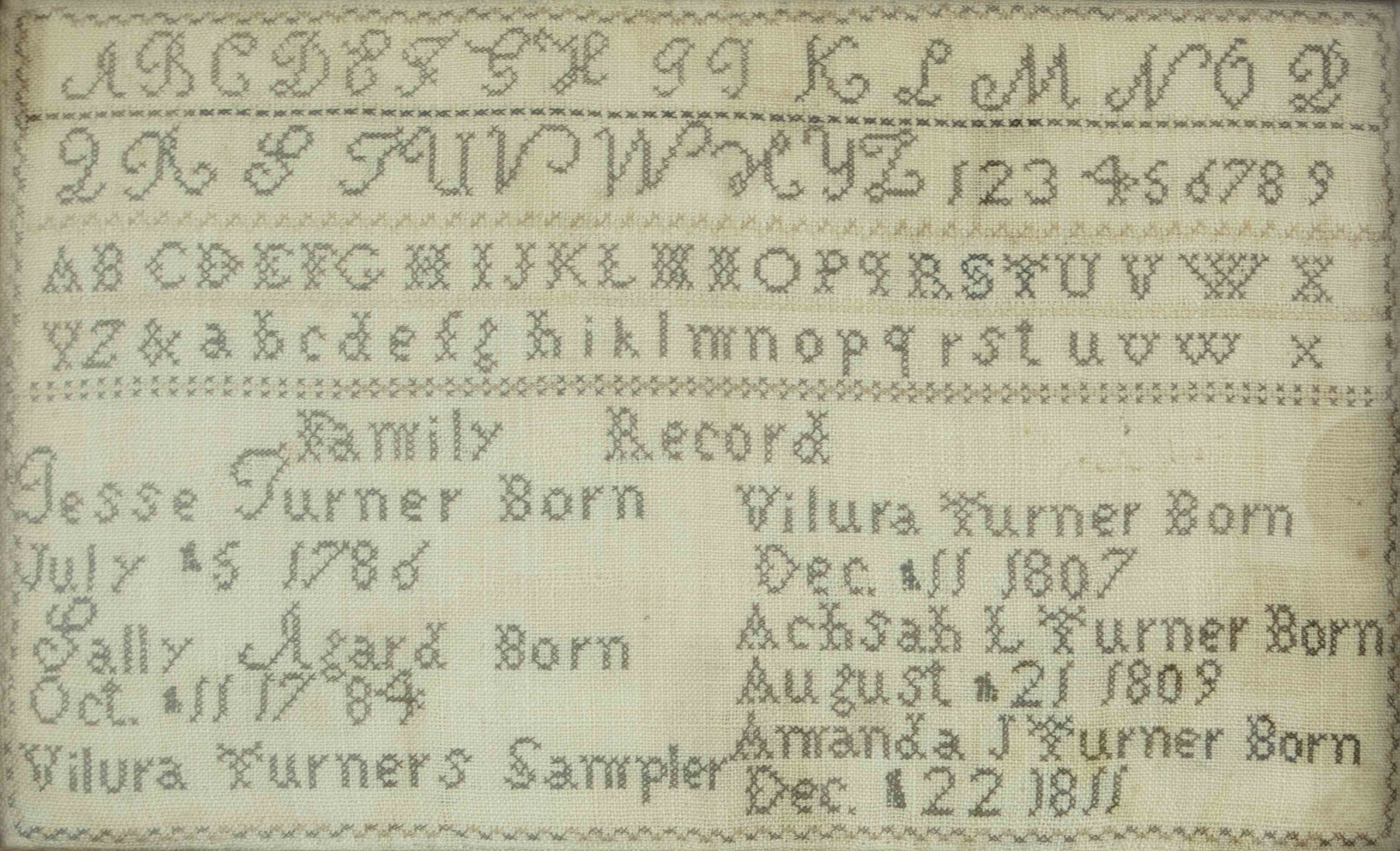

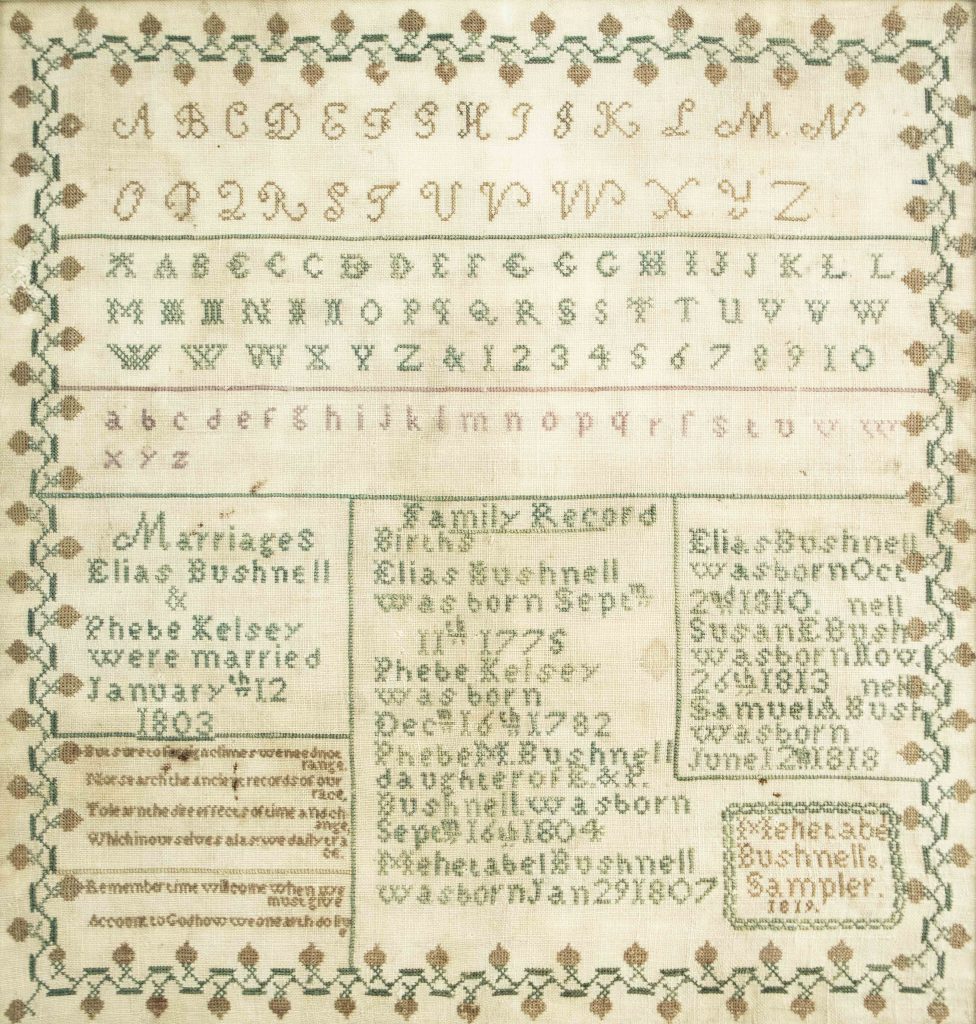

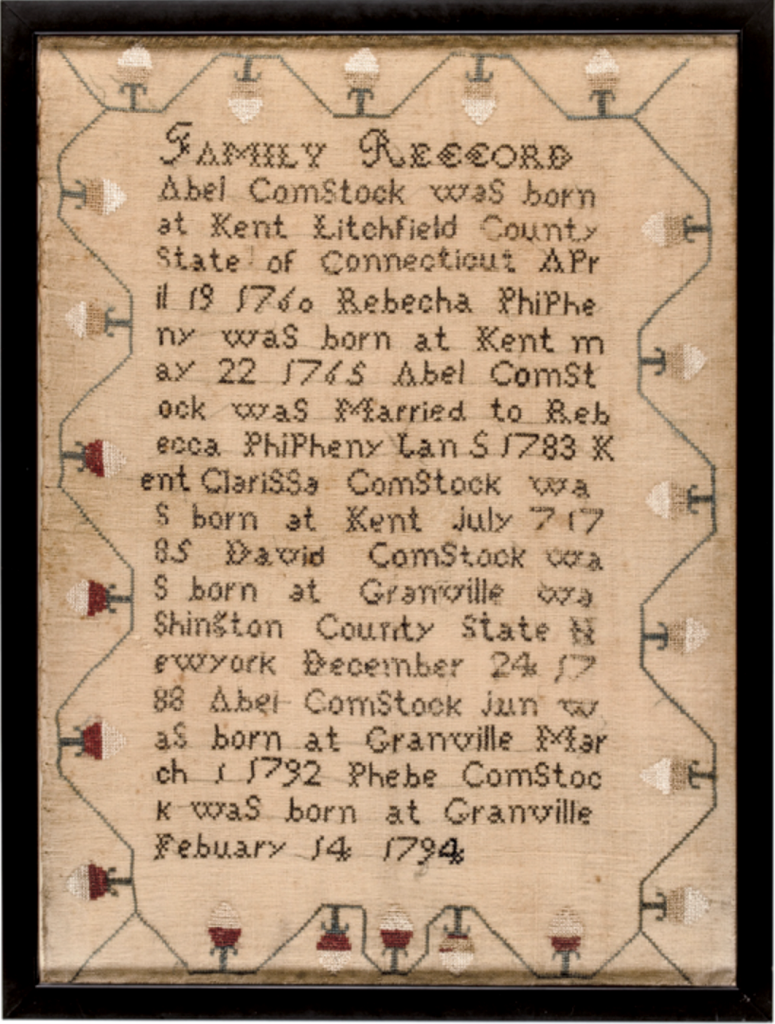

Through painstaking research that often entails hundreds of hours on each piece, Alexandra Peters dives deep into the lives of the sampler makers and the worlds revealed by their needlework. She brings their personal narratives to light. She discovers that girls expressed themselves, told their stories, shared their family history and displayed their literacy through their samplers. They are almost poignant in revealing the untold lives of girls and bringing history alive through personal narratives. “Although girls may have been invisible in history, they left their legacy in these samplers that not only show their creativity and literacy but also tell family stories,” said Peters.

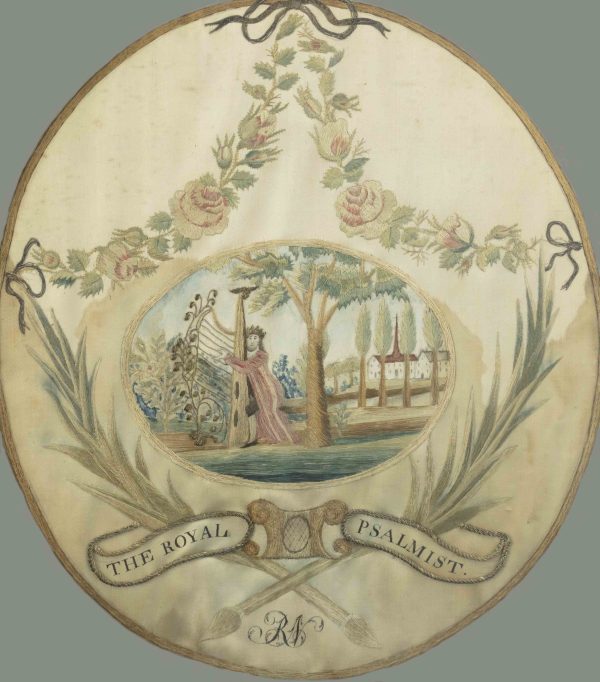

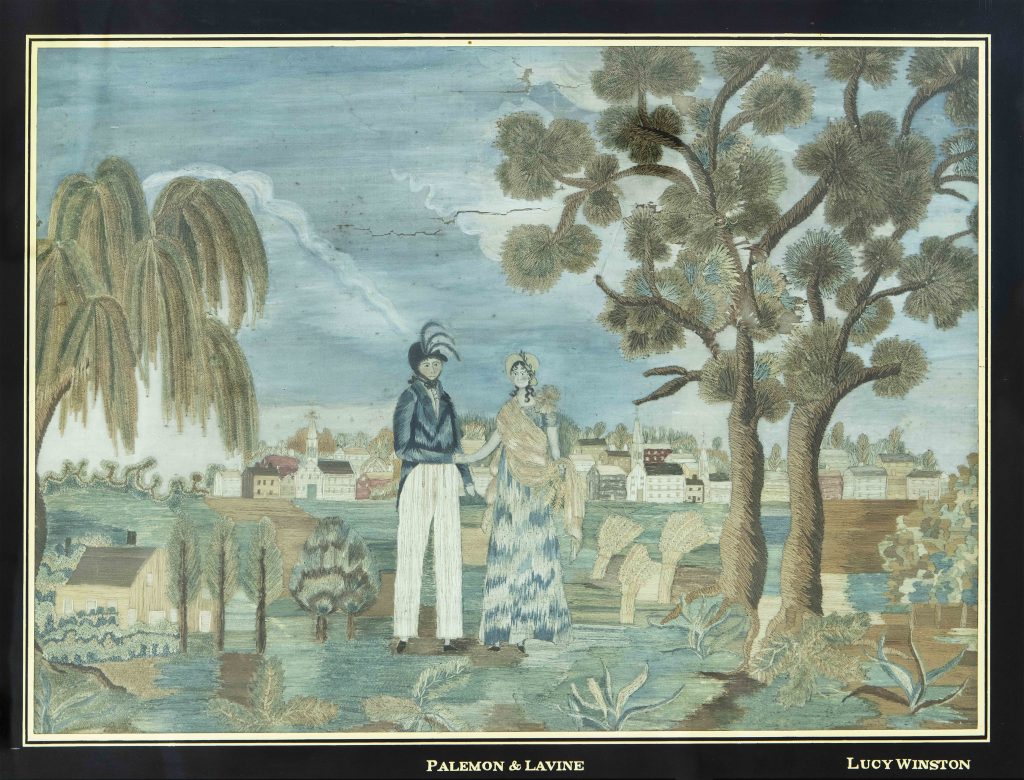

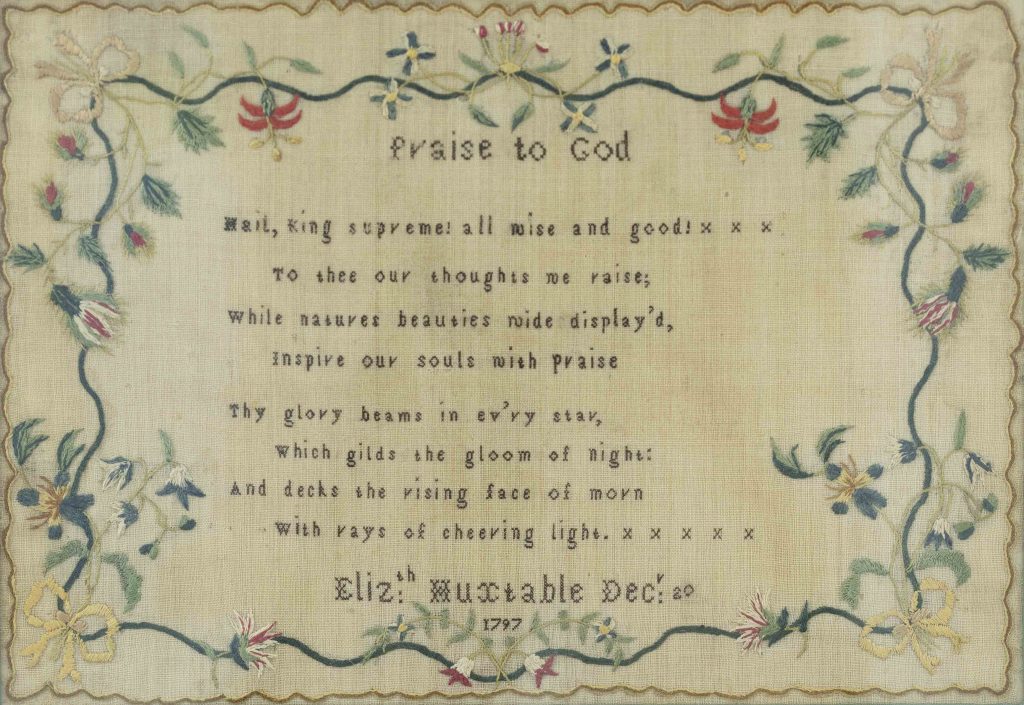

Although the samplers were often the only piece of decoration in a household, they were not considered only beautiful. Peters wrote that the more complex pictorial samplers, made by older girls at academies, were almost like a diploma or dissertation. They would have been ceremonially presented at the academy before a girl left, and then framed and hung on the walls of her parents’ home. They were a demonstration of her achievement and were a symbol of status for a family who could afford to educate their daughter.

“Even the simplest of the marking samplers show us how literate these girls were, what they cared about, their creativity, and their exceptional skills,” said Peters. “The other aspect of this is that sewing was necessary. Sewing was critically important, every girl had to know how to sew. There were no sewing machines even until 1850.”

Through her collecting over the years, Peters has become so familiar with the samplers, that she can even identify the states and the schools where they were completed and the teachers who instructed the girls. The Maine samplers for example, had a full border, usually flowers, surrounding the letters in the Holbein stitch. The Quaker samplers were often darning samplers, or “extracts”, and even three-dimensional globes. Most were done on homespun linen and you either made it or bartered for it. A few special ones were done in all silk which is very difficult to work with or in linsey-woolsey – half wool and half linen.

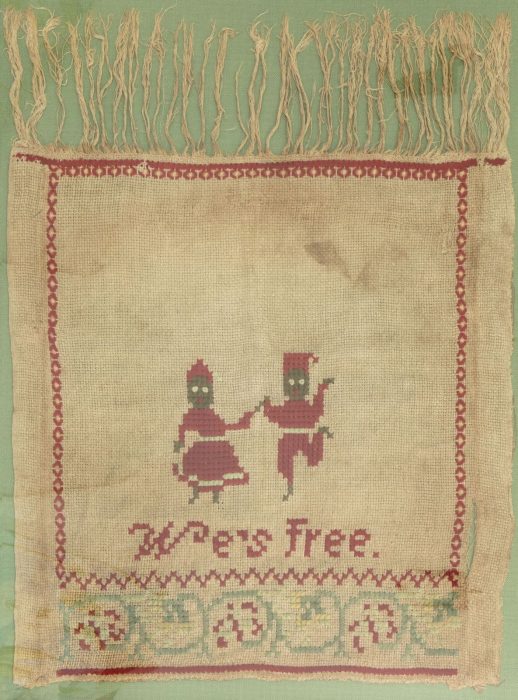

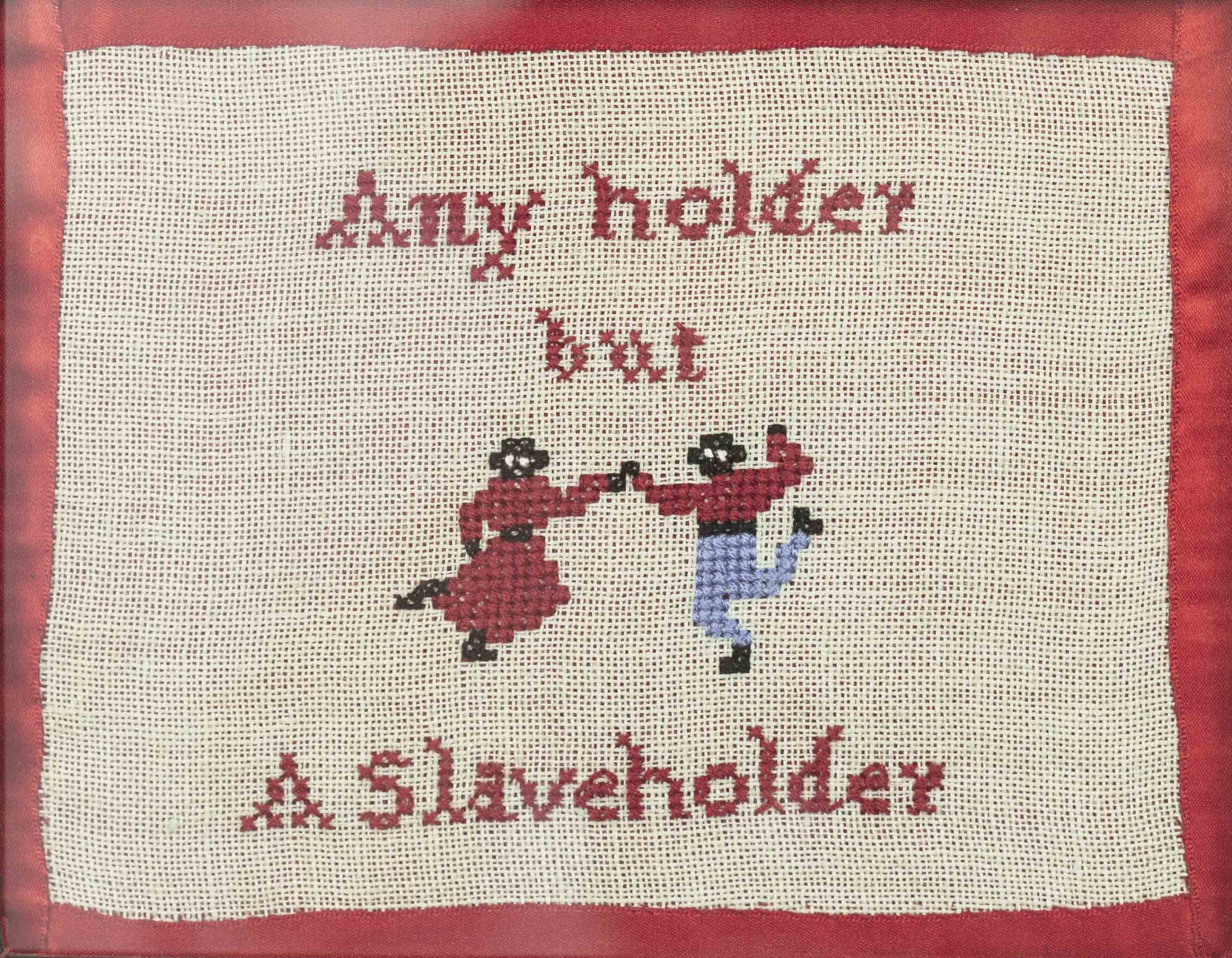

“I find it’s most meaningful and rewarding when you tell history at the individual level – you get a personal narrative that often gets lost, said Brandon Lisi, the curator at the Historical Society. “These samplers were tools of self-expression, even for some underserved people. One of the most inspiring aspects of these works is how they address contemporary issues today, particularly with the slavery samplers.”

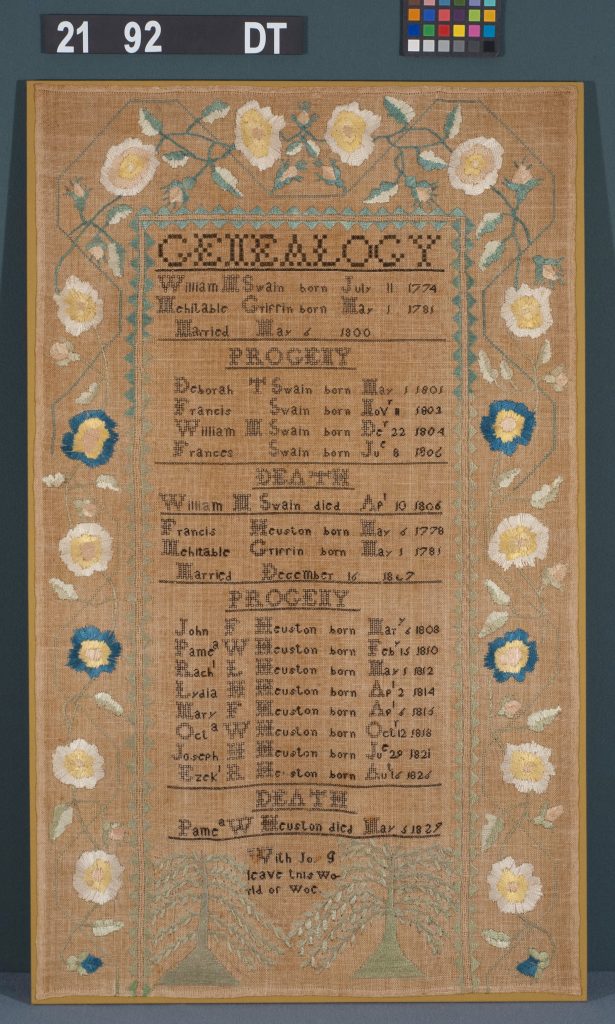

“My favorite sampler,” said Peters, “is by a free Black girl, one of the daughters of Francis and Mehitable Heuston of Brunswick, Maine, who made a very large and beautiful genealogical sampler of her family.” There are very few existing samplers known to have been made by African American girls and yet this is a very typical genealogy sampler from Maine and, most likely, made at a school in Portland. The Heustons were “conductors” in the Underground Railroad network and secretly took in freedom seekers, hid them, and guided them on their way towards Canada. The National Parks Service lists the Heuston Burying Ground in Brunswick Maine, a private cemetery belonging to Mehitable and Francis Heuston, on their list of important and verified sites of Underground Railroad resistance in the United States.

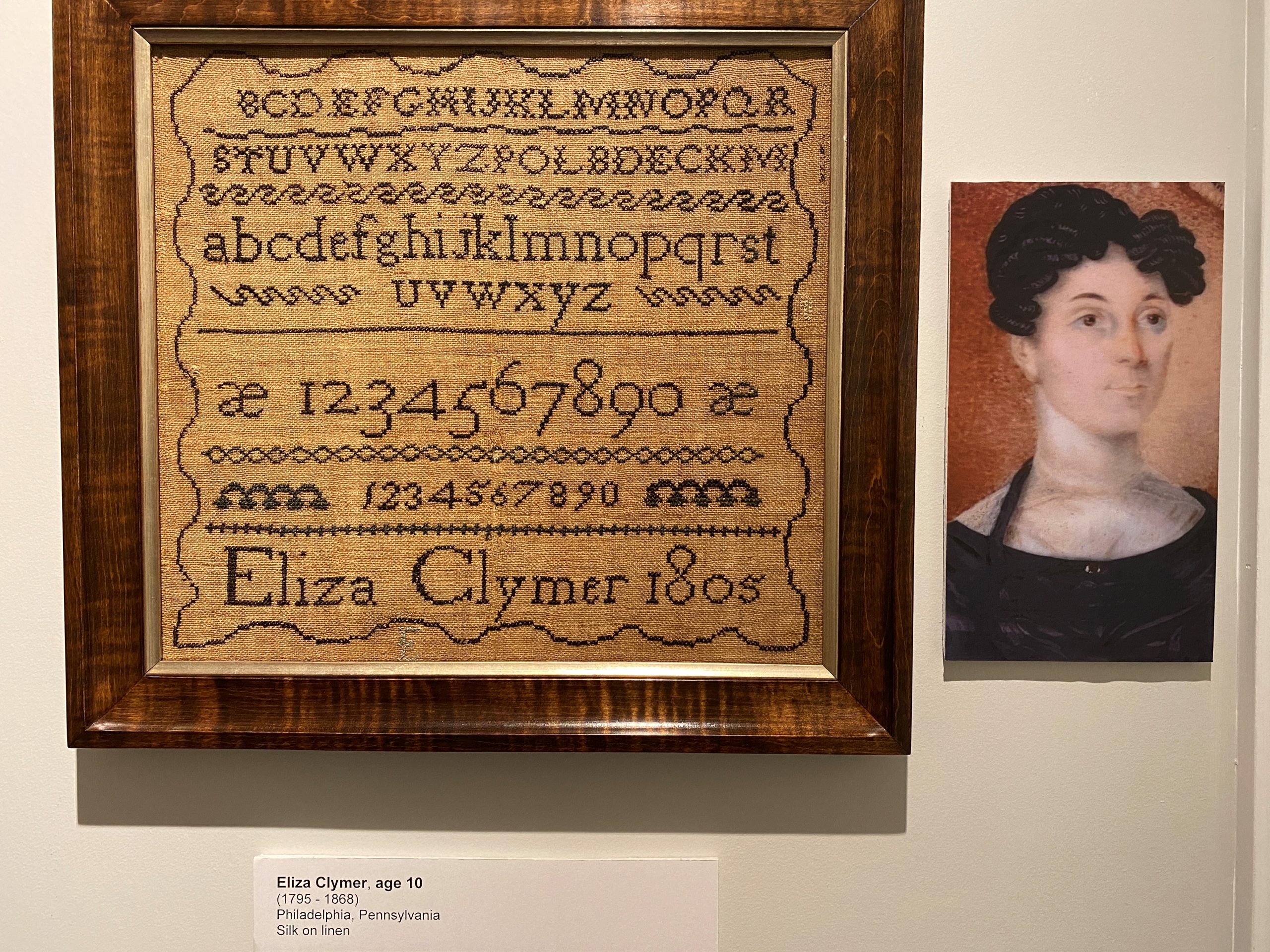

Another example of history coming alive through personal narrative and beautiful samplers is Eliza Clymer’s sampler. Both of her grandfathers, George Clymer and Thomas Willing, were founding fathers and both served as members of the Continental Congress. Clymer is one of the few men who was a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Peters discovered that both Clymer and Willing helped to underwrite the War of Independence and that the British made a point of chasing after both men during the war. However, Willing made his fortune (Mayor of Philadelphia and first President of the Bank of North America) on the backs of enslaved people as a broker of slave auctions. Willing and his partner, Robert Morris, also a signer of the Constitution, used enslaved people on their plantations. Eliza’s other grandfather however, George Clymer, was president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. Clymer was one of the 34 out of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence who did NOT own slaves.

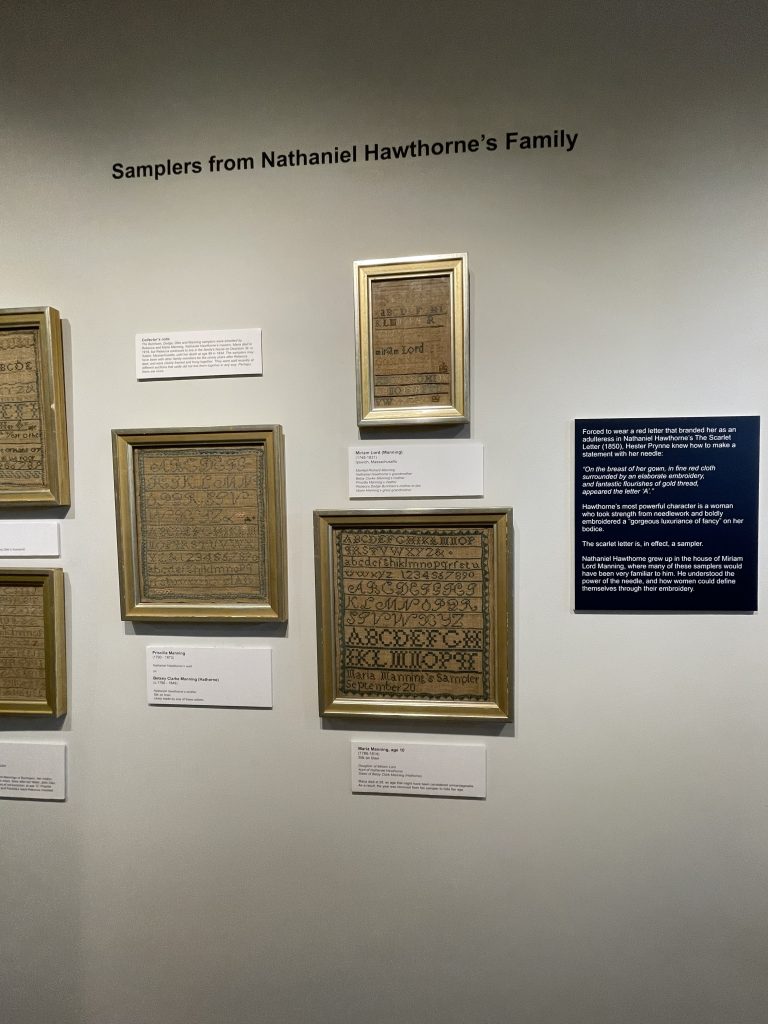

Then there are the samplers from many of the women in family of Nathaniel Hawthorne (his mother was a Manning and married a Hawthorne), an American author most well-known for his book, The Scarlet Letter. Sure enough if his protagonist, Hestor Prynne, did not make her living through needlework. Peters said, “We tend to trivialize the work of women but textiles were so important, they ruled the world and they were worn and displayed and used everywhere in the home.”

Many more groupings of samplers add to the depth and breadth of this extraordinary exhibit: There are samplers by sisters 22 years apart; samplers by a bit older girls who started expressing their sensitivity (a modern concept) during the Romantic movement and copied famous paintings from literature; some girls in England sewed world maps revealing their confidence about England’s place in the world (although most of the samplers are by girls in America); some of the samplers are from Quakers; other samplers showed the development of towns and buildings. All of the samplers are beautifully framed and presented.

Peters said she bought her first sampler in the early 1990s as she was “charmed” by it but now she buys from dealers who specialize in samplers and at auctions online and really knows what she is looking for. Many of Peters’ samplers have been professionally conserved by textile conservators but never repaired. “The original samplers would have had more colors. The bleaching UV rays of the sun that take out color are the greatest enemy of textiles,” said Peters.

“Our role as historical institutions is to communicate why history matters,” said Lisi.

“As it applies to Alexandra’s show, she presents an art and skill that was so important in telling the lives of these individual girls. Often it is an uphill battle to convince people why history matters but there is a real commitment already by people in this area to know and learn about their history.”

On Saturday August 6 at 11:00 a.m., Friday August 12 at 2:00 p.m., Friday August 26 at 1:00 p.m. and Saturday, August 27 at 11:00 a.m. and by individual request, Alexandra Peters will give tours of the exhibition at the Sharon Historical Society & Museum, 18 Main Street, Sharon CT 06069. Registration is required. Please call 860-364-5688. The Historical Society is open Wednesday through Friday from 12 to 4 pm and Saturday from 10 am to 2 pm. Sharon Historical Society & Museum is a membership organization ($35 per year) with free admission and a research library.

By Victoria Larson, Editor, Side of Culture

A moving and important exhibition. This is an important collection.

This article has wonderful content and images. I really value this type of history. Thank you for contributing to our body if knowledge.