In a German city renowned for music and musical history sites, Mendelssohn Haus (Mendelssohn House) uses original artifacts and modern technology to bring vividly to life the famous Romantic composer’s world and art. The setting in Leipzig is ideal: an apartment, the last home of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847) and his family, has been authentically restored in what is now a three-story museum showcasing everything from Mendelssohn’s study to an electronic installation that allows visitors to conduct a virtual orchestra. Fascinating exhibits on another floor present the less-known life and music of Mendelssohn’s sister, Fanny Hensel, a composer and pianist.

In 2022, Mendelssohn Haus (closed due to Covid-19 restrictions: check website for updates) will mark the 175th anniversary of Mendelssohn’s death and the 25th anniversary of the museum’s opening, making it an excellent time to visit Leipzig’s cultural treasures. This and other musical sites such as the Bach Museum and St. Thomas Church are part of the Notenspur, a music trail. Celebrations will include a birthday concert on February 3, 2022, and a Mendelssohn in Spring event May 27 to 29 with a garden festival and concerts. A fall highlight, the Mendelssohn Festival Leipzig will take place October 31 to November 6, 2022. Since 2021, this festival has been a collaboration between Mendelssohn House and the Gewandhaus, where Mendelssohn was conductor. Concerts with international artists will take place in both venues.

Highlights of Mendelssohn House

A short walk from Leipzig’s historic center, the neoclassical building that is now Mendelssohn House was new in 1845 when the family moved in. The museum opened in 1997 with a reconstruction of the composer’s second-floor apartment (first floor, in European numbering). Today visitors can spend an hour or two in more than 20 rooms and galleries on three floors. Labels in German and English, plus plenty of music—that universal language—make exploring easy. Outside, the garden, recreated to Mendelssohn’s era, is a relaxing spot to stroll or reflect.

In the effectorium, a dramatic exhibit on the entry-level floor, visitors try their hand at conducting one of Mendelssohn’s orchestral or choral works. Thirteen posts represent different instruments from Mendelssohn’s era or vocal registers, and a podium holds an electronic copy of the score. It’s possible to adjust tempos, select instruments, even adjust the room color during this unique experience. Also on this floor, a reference library includes devices for listening to music and film clips.

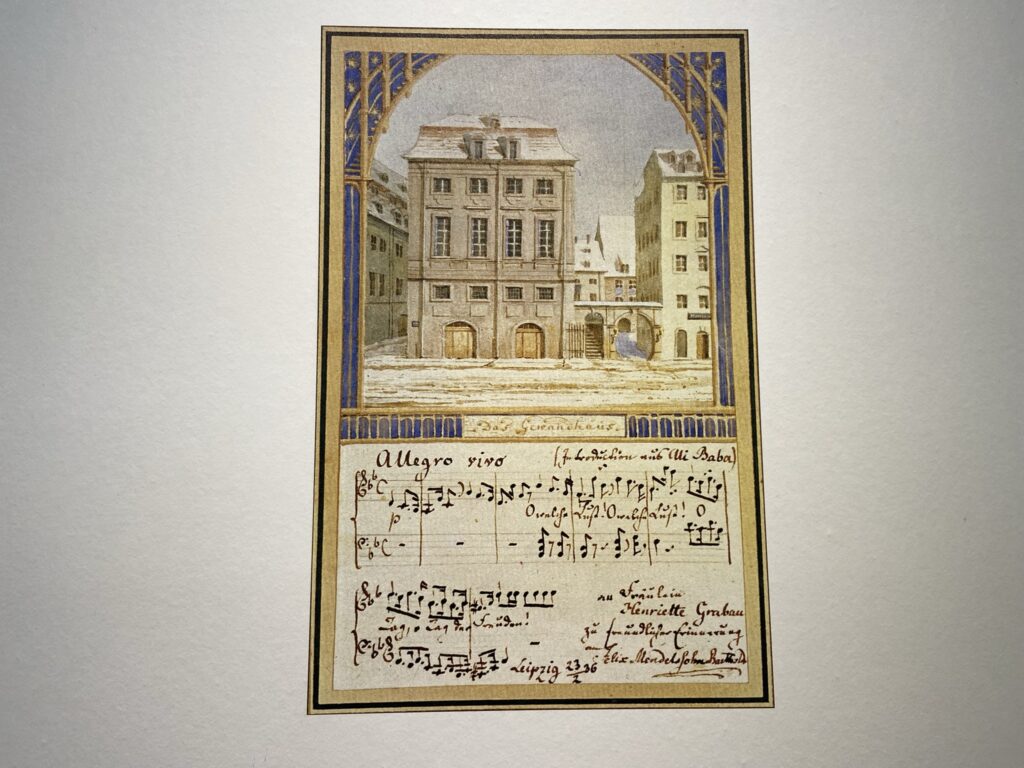

Another gallery focuses on Mendelssohn’s work as conductor and musical director of Leipzig’s Gewandhaus Orchestra from his appointment in 1835 at age 26 until his early death at 38. A dollhouse-size model shows the orchestra’s building at the time. During his tenure, Mendelssohn focused on improving the status of the orchestra. He helped shape the role of the modern conductor, using a baton and standing in front of the orchestra, and advocated for better pay for musicians. Another notable accomplishment was his founding of the Leipzig Conservatory of Music, Germany’s oldest university school of music, in 1843.

Visitors walk up the original wooden stairs to enter the apartment of Felix and Cécile Mendelssohn and their children. The small study, with piano and desk, is based on a watercolor the composer painted of the room. A bust of Bach is a reminder that Mendelssohn, at the age of 20, initiated a Europe-wide revival of Bach’s works by leading performances of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in Berlin: Bach had been largely forgotten after his death in 1750. Mendelssohn composed many works in the apartment, including the oratorios Elijah and the unfinished Christus.

Besides family rooms with some original pieces and period Biedermeier furnishings, the apartment has displays examining Mendelssohn’s family and his relationships with contemporaries, including Schumann. A musical child prodigy as both composer and pianist, Mendelssohn was born into a wealthy Jewish family but was baptized at age seven, along with his brother and sisters. His father, Abraham Mendelssohn, believed the children would integrate more successfully into society as Christians; he also took the name Bartholdy.

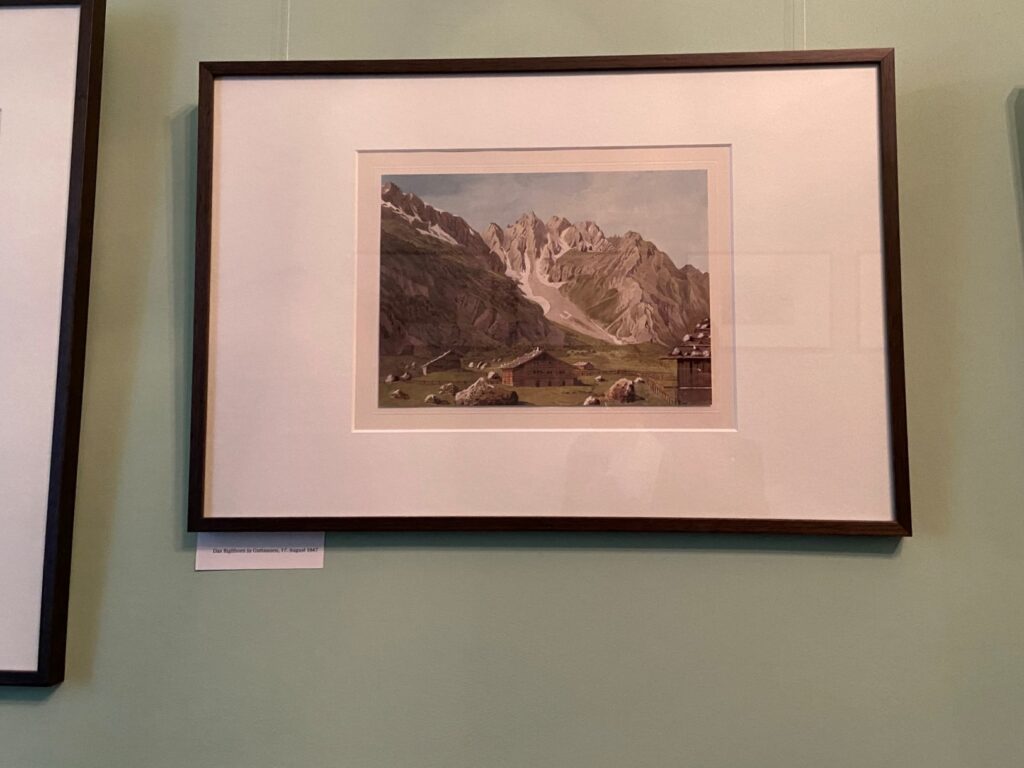

The apartment’s expansive, elegant music salon was the site of concerts in Mendelssohn’s day, a tradition that continues today. Another room displays exquisite watercolors the multi-talented composer created during business and family trips around Europe. Also on this floor is the bedroom where Mendelssohn died from a stroke.

For many visitors, the museum’s third-floor galleries, which opened in 2017, will be a revelation: they are dedicated to Mendelssohn’s older sister, Fanny Hensel (1805–1847), a musical prodigy like her brother. The siblings remained close throughout their lives, writing hundreds of letters. Mendelssohn sought and valued her critical advice on his compositions. Fanny died, also of a stroke, a few months before her brother. Despite Fanny’s talents and intensive musical training, the siblings’ paths diverged because of the traditional domestic role assigned to women of the time. Fanny pursued her deep musical interests mostly in the personal realm rather than professionally.

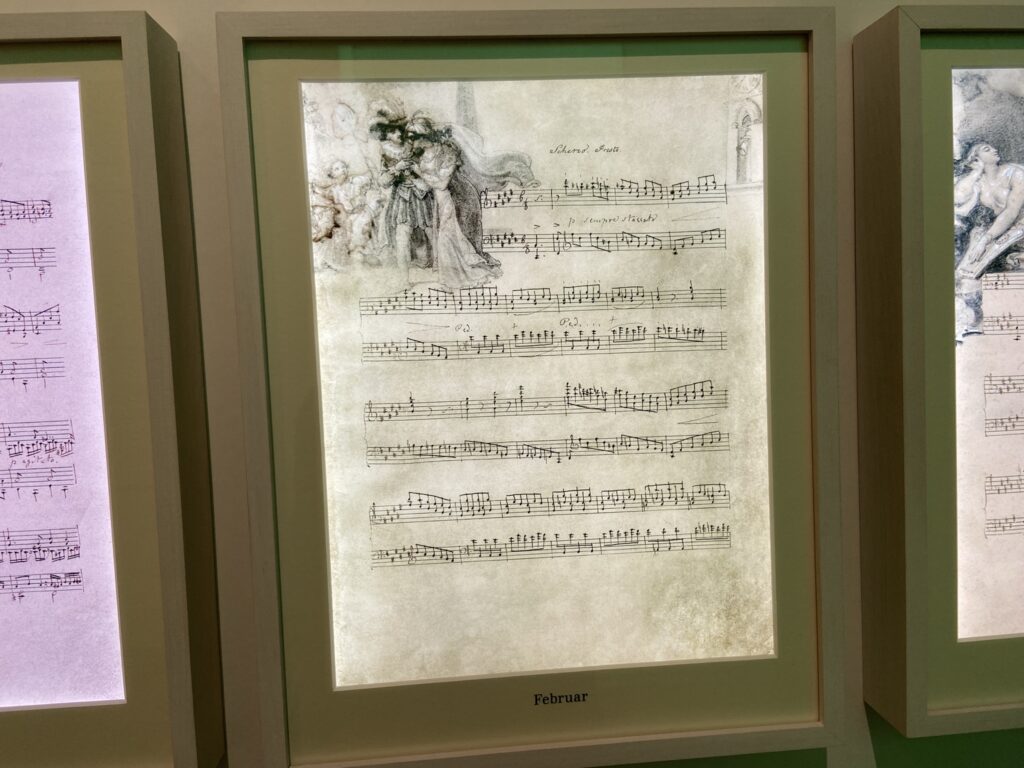

An outstanding short film describes how Fanny married artist Wilhem Hensel in 1829 and lived in Berlin in the Garden House of her father’s large home. She began a distinguished series of private Sunday concerts, attended by over 150 people each week, which continued throughout her life. These included Fanny playing the piano (she was an outstanding pianist) or conducting her own works. Although she produced over 450 musical compositions, only a few were published during her lifetime; even her brother had mixed feelings about Fanny publishing her work. Visitors can listen to Fanny’s 1841 work Das Jahr (The Year), a cycle of beautiful piano pieces about each month, in different galleries. Around this floor, rooms offer recreated scenes from Fanny’s home.

The museum’s third floor holds the International Kurt Masur Institute, part of the Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Institute. The institute’s mission is to broaden cultural perspectives through music, particularly with young people. It’s named for the longtime conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, who among his accomplishments led the effort to preserve Mendelssohn House, which survived World War II bombing but was threatened with demolition.

Salon Concerts and More

Weekly chamber music concerts (extra charge; reserve online) in the apartment’s historic music salon offer a memorable way to engage with the museum and support musicians. The website lists other special programs such as a weekly tour, Mendelssohn’s Footsteps, which is a museum tour and city center walk. The educational department offers special programs focused on children and school groups.

Side Dish

Martin Luther visited Auerbachs Keller (currently closed except for takeout, due to the pandemic; check website for reopening) and so, centuries later, did Goethe, who used the restaurant in a scene in Faust. This popular Leipzig institution includes a cavernous, handsomely wood-paneled cellar space dating from 1912 that is perfect for feasting on Saxon specialties, hearty meat dishes, and delicious beer. Sauerbraten with dumplings and beef roulade with red cabbage are classics, and there’s a choice of international offerings as well.

All photos are courtesy of the author, Linda Cabasin, except where noted.

Linda Cabasin is a travel editor and writer who covered the globe at Fodor’s before taking up the freelance life. She’s a contributing editor at Fathom. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter at @lcabasin.

Excellent article, we want to go!

Thank you!

I recommend the Phillips strongly! The Picasso exhibit starting in February will, I’m sure, be as thoughtful and well-presented as other shows. Plus…who can resist the Luncheon of the Boating Party?