November is Thanksgiving month, the quintessential American holiday that began in seventeenth-century Massachusetts when the ship Mayflower, dropped anchor off the coast of Cape Cod. Its cargo was 102 English people, many of whom were Separatists escaping religious persecution by crossing the Atlantic. Not wanting to join the Church of England was an act of treason. Today, Thanksgiving has evolved into an annual nationwide celebration when family and friends gather, often traveling from afar, to watch a football game or Macy’s Parade on television, go shopping and share a traditional meal, consisting of turkey, cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie.

Plimoth Patuxet Museum is America’s Museum of Thanksgiving, a place where ancient traditions of gratitude in both the Pokanoket Wampanoag and English cultures merged in the autumn of 1621, and a new holiday of gathering and giving thanks for countless life blessings began. In this time of Covid, a time of global pandemic and upheaval around the world, it feels particularly important to express gratitude for what we have.

It seems improbable that all we know about the 1621 harvest feast is based on a December 1621 letter written to a friend in England by Edward Winslow, member of the Leiden, Holland Separatist group who later served as Plymouth’s third governor. This letter was reprinted for all to read in Mourt’s Relation (1622), an account of Plymouth Colony’s first year.

Winslow wrote, “Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruits of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor and upon the Captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”

Later, Bostonian minister Alexander Young designated this harvest feast the First Thanksgiving in his 1841 book, Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers. Despite disease and hunger, the Plymouth settlers or Pilgrims came together with their Native American neighbors to give thanks. But by the 1850s, the American Union was deteriorating under the pressure of slavery. In an attempt to ease North and South tensions, journalist Sara Josepha Hale launched a national campaign to establish a day of thanks. She published recipes in her magazine and wrote hundreds of letters to support her cause. Later, President Abraham Lincoln agreed and in 1863 issued the Thanksgiving Proclamation, establishing a holiday that he hoped would aid America’s healing process from the division of the Civil War.

Celebrations after a successful crop harvest, however, are as old as the harvest itself. In ancient Mesopotamia, humans were sacrificed to the harvest gods; in Egypt, a sheaf was offered to the wheat mother. Recent traditions can be traced to Lammas, a medieval holy day on the first of August. Christians took bread baked with the first flour of the season to church to be blessed. By Victorian times, Lammas Day was no longer a religious festivity. However, the concept of rejoicing for a bountiful harvest remained alive on the farm where good weather, soil fertility and abundant crops were never taken for granted.

When the last stalk fell in medieval England, men, women and children ran out of their cottages singing the traditional harvest song:

Harvest-home, harvest-home,

We have ploughed, we have sowed,

We have reaped, we have mowed,

We have brought home every load,

Hip, hip, hip, harvest-home!

Before the railroad distributed grains far and wide, the quality of the local harvest meant the difference between eating or not eating. Farmers well understood what happened when weather or insects destroyed their crops. In England, the harvest marked the climax of the rural year and was one occasion when class differences were subordinated to mutual interests. The farmer who owned the harvested crop was obligated by custom to provide a feast for the reapers and their families. Long trestle tables, decorated with flowers, fruit and small corn dolls, displayed a varied and plentiful menu with most edibles grown or raised on the farm.

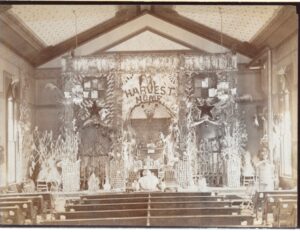

By 1861, England’s Anglican Church encouraged churches to adopt the custom of decorating their interiors with the bounty of the fields. Called Harvest Home, the day became popular, and as a result, farmers were willing to turn their responsibility for holding harvest appreciation to the parish. To those of Christian faith, the celebration was one of praise for God’s blessings. Many early images dating around the 1880s to the 1900s from both England and America illustrate churches’ altars filled to the brim with the abundance of God’s glory—flowers, fruits and vegetables.

Although the first year in Plymouth was hard, plagued by exposure, cold, hunger and disease, by early fall of 1621, Governor William Bradford declared that the 50 surviving Plymouth Colony members should “rejoice together”—a New World Harvest Home celebration, a sentiment the Pilgrims would have understood from their lives in England.

The Wampanoag had taught the colonists how to successfully plant corn, using herring as fertilizer; how to tap maple trees for sweet sap and where to find eels, a delicacy that reminded the Pilgrims of home. Thus, the 1621 harvest celebration, enjoyed by both Colonists and Native Americans, was a result of working together—early diplomacy, if you will. Certainly, it had been a matter of survival for both sides.

Perhaps the greatest link between the 1621 Feast and today’s holiday is the menu of New England foods. The mention of deer in Winslow’s account is significant. Although common in Massachusetts, venison could not be sold by law in England, and was subsequently only enjoyed by the landed gentry. On the other hand, for the Wampanoag, like the bison or buffalo in the American West, it not only provided nutrition but also the raw material for clothing and tools. In addition, contemporary sources note plentiful fish, and shellfish as well as late fall crops including Jerusalem artichokes, wild onions and garlic, Concord grapes and native walnuts and chestnuts.

The cranberry deserves special mention. Growing wild in low lying areas called bogs, the Wampanoag had early discovered its versatility. A pink blossom appears in late spring, resembling the head of a crane, hence the name “craneberry.” In the fall, the blossom turns into a tart berry. Native Americans enjoyed the berries, fresh or dried, raw or cooked, and used them in a number of ways; added to venison, cranberries were an essential ingredient in pemmican, a dried food that provided protein and vitamins during winter’s scarcity. Cranberries were also mashed and shaped into poultices to draw out poison from arrow wounds, and the juice transformed blankets a rich burgundy color.

There were at least 140 participants at the First Thanksgiving. About 50 colonists remained after the harsh winter, and according to Winslow, Massasoit brought 90 of his men to the table. Native sobaheg or stew, boiled bread and nusamp or corn porridge were probably on the menu. Period cookbooks in England offered many recipes for “seething” (boiled or fried mussels), a common English shellfish at the time as it was in New England. An autumn version of sobaheg was adopted by the colonists and would have included venison, turkey, goose or duck.

Plimoth Patuxet Museum gives context to Thanksgiving where it began. At Historic Patuxet, you journey to learn about the Native peoples who inhabited the region for thousands of years before the arrival of the English. Nearby is the 17th century village, a re-creation of the Pilgrims’ farming and maritime community along the shore of Plymouth Harbor. It is an early Plymouth, complete with timber-framed houses furnished with reproductions of objects the Pilgrims would have owned as well as aromatic kitchen gardens and heritage breeds livestock. When you meet a person wearing historical clothing, he or she is playing the role of an actual inhabitant of Plymouth Colony, conversing as if history were not in the past.

Two satellite sites include the Grist Mill and the Mayflower II. At the reconstruction of the original 1636 grist mill on Town Brook, take a look at the mill’s workings from the 200-year-old millstones grinding corn to the ecology of the brook that has powered mills throughout the centuries. In the spring, you may see herring running upstream to spawn. Outside the mill, water diverted from Town Brook provides power for the 14-foot diameter waterwheel. On grinding days, watch the miller work the water wheel, gears, and stones to end up with freshly stone-ground organic cornmeal, grits and other grains that you can take home.

The full-scale reproduction of the tall ship that brought the Pilgrims to Plymouth in 1620, the Mayflower II, after a 3-1/2-year restoration at Mystic Seaport, has returned to her berth in Pilgrim Memorial State Park to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival.

At the Craft Center, the Humoral Gardens are period gardens of a time when medicine was hampered by wrong ideas about the human body. Most doctors thought there were four fluids or “humors” in the body: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile and that illness was the result of an excess of one humor. Treatments, based on superstition, might include leeches, mice, ferrets, maggots to remove dead flesh and spider webs to stop nosebleeds.

Today, foodways take a prominent place in the popular Thanksgiving dining programs. Fresh ingredients, authentic flavors, festive surroundings and a profound sense of history, unknown anywhere else in America, permeate the holiday family-style dining experiences: the Thanksgiving Day Homestyle Buffet, the Story of Thanksgiving Dinner and the New England Harvest Feast, offering authentic 17th-century dishes, such as Boiled Bread (a small patty made of cornmeal with crushed nuts and berries that is dropped in a pot of boiling water and when done, rises to the top), a “Sallet,” Mussels Seeth’d with Parsley and Beer, A Dish of Turkey, A pottage of Cabbage, Leeks and Onions, A Sweet Pudding of Native Corn, and Stew’d Pumpion.

At Plimoth Patuxet Museums, food best preserves history and is a wonderful addition to our understanding of the very first Thanksgiving meal.

All photos in this article are courtesy of Plimoth Patuxet Museums, unless otherwise noted.

Cynthia Elyce Rubin, Ph.D. is a visual culture specialist, travel writer and author of articles and books on decorative arts, folk art and postcard history.

Where would I find information on Issac Allerton, my relative who was on the Mayflower. Was he a Christian or just on a commercial venture?