Deceptively simple and functional but meticulously detailed: At the Pope-Leighey House in Alexandria, Virginia, these characteristics of Frank Lloyd Wright’s design impressed the home’s owners and still inspire today’s visitors. The small Usonian house, completed in 1940 as an early example of Wright’s radical ideas for affordable housing, is also a study in preservation—and personal determination—that remains timely as individuals and communities seek to save buildings that matter to them.

When this unique house faced demolition in the 1960s, owner Margaret Leighey donated it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the privately funded, nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting the country’s historic buildings and neighborhoods. The only Wright house open to the public in Virginia, the Pope-Leighey House was moved to the grounds of Woodlawn, a former plantation house that was the first acquisition of the National Trust. They can be visited separately, but together these historic houses, just 20 miles from Washington, DC, reveal a wide range of American experiences.

The House That Began with a Letter

Loren Pope (1910–2008) was a copy editor for the Washington Evening Star earning $50 a week in 1938 when he became enthralled with Frank Lloyd Wright, who was enjoying international acclaim for large projects such as Fallingwater. Pope wrote Wright a flattering letter asking the architect to design a house his family could afford, and the answer came: “Dear Loren Pope, Of course I am ready to give you a house.” Wright had long been intrigued by the challenge of creating beautiful but affordable houses for the middle class that were American in style, calling such houses Usonian (Wright used the term Usonia for America). Despite resistance from mortgage lenders due to its unconventional design, by 1940 the L-shaped, 1,200-square-foot home was completed in Falls Church, Virginia, at a cost of $7,000 rather than the original $5,000. When Loren and Charlotte Pope, needing more space, put the house and its Wright-designed furniture up for sale in 1946 for $17,000, they had over 100 responses but chose Robert and Marjorie Leighey because of their appreciation for the house’s spirit.

The Leigheys’ commitment was tested: By the early 1960s, it was clear that Interstate 66 would be routed through the site, and in 1964 the state notified Marjorie Leighey (Robert had died in 1963) that the house would be condemned. Leighey gave her home and its contents—and the money the state paid her for the house—to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Because all efforts to have the highway rerouted failed, the Pope-Leighey House was taken apart, moved 15 miles, and reconstructed on Woodlawn’s grounds. Marjorie Leighey lived in the house she loved until her death in 1983, but it has been open to visitors since 1965. One more challenge lay ahead: Unstable clay underneath the house caused its base to crack, making it necessary to relocate the house to a spot 30 feet away in 1995.

Wright’s innovative designs and the passage of time mean maintenance and preservation are ongoing. One recent project was conserving the Pope-Leighey House’s exterior cypress, which had weathered to gray, in contrast to the original specification that exterior and interior wood have the same treatment. A current priority is repairing the house’s flat roof, using a material that will protect the roof and return it to its original design.

Experiencing the Pope-Leighey House

The Pope-Leighey House and Woodlawn offer guided tours from late April through December (sign up on the website for one or both tours, or view the National Trust’s free virtual tour of Pope-Leighey). Enthusiastic, knowledgeable guides provide insight into many architectural details. Wright’s Usonian ideas, including an open-plan living space, created a sense of spaciousness and light and influenced suburban American homes.

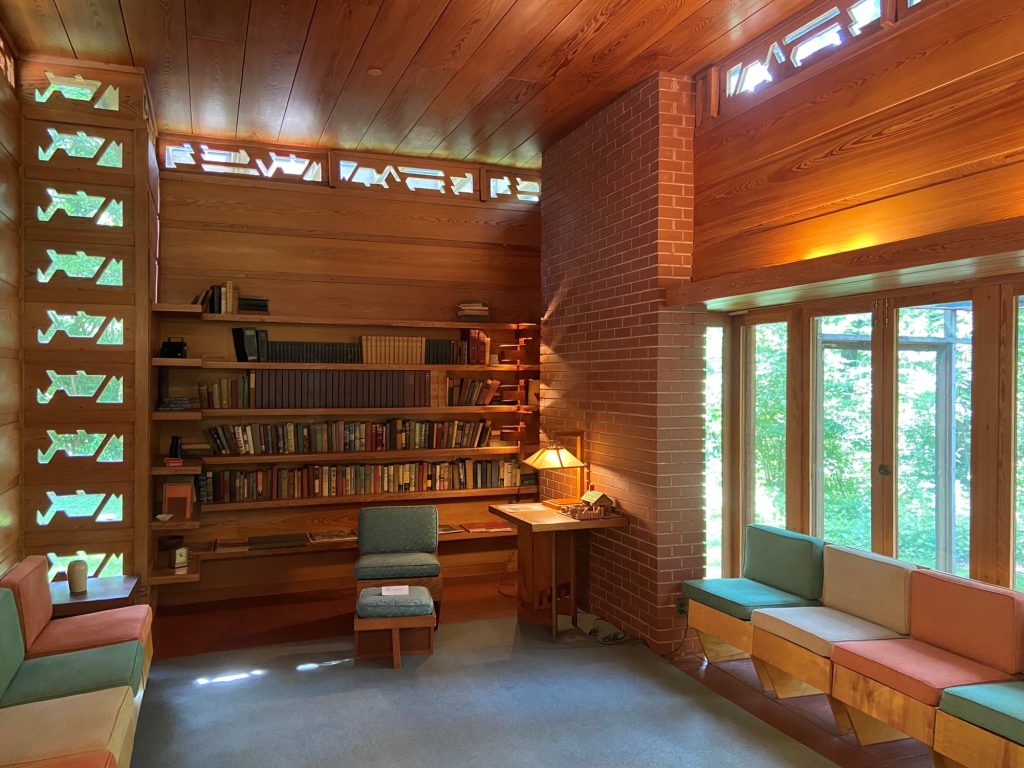

The house is surrounded by trees, visible through the large windows that Wright favored to provide light and integrate the house’s interior with nature. Though the basic materials in its 1,200 square feet are simple—wood (including unpainted cypress and plywood), brick, glass, and concrete—the flat-roofed, one-story L-shape used here and in other Usonian houses was a significant departure from typically boxy houses. Cypress wood board-and-batten siding and rows of brick used on the exterior and interior reinforce the house’s horizontal feeling. Tucked into the juncture of the two wings, the entrance is under one of Wright’s innovations: a carport with a cantilever overhang.

An entryway, with a study and a tiny but efficient kitchen off to one side, leads to an open living and dining space with a fireplace (important in Wright’s houses), modular seating designed by the architect for maximum flexibility, and a light-filled dining area with glass doors. The soaring, 12-foot-high ceiling in the cypress-paneled main living space features clerestory windows with stylized geometric cutouts; the pattern appears throughout the interior. The house has radiant heating via the Cherokee red concrete slab floors. In the longer arm of the L-shape, a narrow, wood-lined hall leads to a bathroom and two bedrooms. Large windows make the small rooms feel more spacious, but the practical Popes had to convince Wright to design wooden rails so that they could hang curtains for privacy. Overall, the effect of the house is stunning, creating a feeling of light and openness but also warmth and serenity, and Wright considered it among his most successful Usonian work.

Living in a Wright house required accepting a certain style of living, including adjusting to the lack of a basement or attic, but owners often felt enthusiastic about the experience: Margaret Leighey said to the Washington Post, “Little by little, your pretensions fall away and you become a more truthful, more honest person.” Loren Pope wrote of the house, “I have been away from it more than I’ve been in it, but spiritually I never left.”

Special tours and programs (see the website) are other options for experiencing the Pope-Leighey House. Many focus on nature and well-being, in keeping with the spirit of the house. Examples include Designing American Living, which looks at the intentions of the architects of Pope-Leighey House and Woodlawn; Wright at Twilight, when visitors can stay after public hours; Forest Bathing; and a tour focusing on the house’s Japanese aesthetic. Yoga Nidra sessions are sometimes offered, and an annual celebration acknowledges Wright’s June birthday.

Woodlawn and Arcadia Farm

A short walk from the Pope-Leighey House and well worth visiting, Woodlawn is an imposing redbrick, early Federal-style plantation home built in 1805 on George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate. The now-126-acre site is a 10-minute drive from Washington’s home. Washington gave the house and 2,000 acres of land to his step-granddaughter Nelly Parke Custis and Lawrence Lewis, his nephew, as a wedding gift. Dr. William Thornton, the architect of the U.S. Capitol, designed Woodlawn. About 90 enslaved people also lived here, working in the house and on the land; today Woodlawn is researching their stories and sharing them along with those of all the people who lived on the site. In 1846, anti-slavery Quaker families bought the plantation and sold parts of it to anti-slavery and free Black farmers, making Woodlawn a successful model of free-labor agriculture in slavery-dependent Virginia. At a program on June 30, Judge Rohulamin Quander will speak about his book The Quanders: Since 1684, An Enduring African American Legacy, including the family’s connections to Woodlawn and the area.

Also on the grounds is Arcadia Farm, part of Arcadia Center for Food and Agriculture, a nonprofit working to create a more fair and sustainable food system in the Washington, DC, area.

Side Dish

Nearby Richmond Highway (U.S. 1) in Alexandria, a busy multilane road with gas stations, chain hotels, and strip malls, has convenient dining options. Owned by a Black family, Della J’s Delectables in Mount Vernon Plaza serves up Southern home cooking in a comfortable, casual setting. Among the sandwich choices on the lengthy menu are a fried shrimp po’boy and barbecue pulled pork or chicken on a brioche bun. A side order of corn bread is essential.

Linda Cabasin is a travel editor and writer who covered the globe at Fodor’s before taking up the freelance life. She grew up in a 1,400-square-foot, 1950 ranch house with some of Wright’s Usonian features. Linda is a contributing editor at Fathom. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter at @lcabasin.

By Linda Cabasin

Featured Photo: From the back, the two areas of the one-story, L-shape house are clear: living areas to the left, bedrooms to the right. The dining area’s French doors open to a patio. Photo by Mike Squires.

I am a Wright scholar and have been for almost 70 years but I was not familiar with this Usonian home. I wish I could see it in person but I am not able to travel much any more. It looks like a perfect example of this style – compact but rich in detail and charm. Since it was built the year I was born is an added surprise. So glad it was not demolished.