Photo by Julian Parker-Burns, courtesy of Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

A woman had to be brave to take on the issue of slavery, and at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut, the 19th-century writer’s home and research collections explore Stowe’s legacy and its relevance today. The center also connects Stowe’s concerns with current issues of social justice. During tours, participants are encouraged to discuss issues rather than only listen to a guide talk about the house. Several modern galleries present changing views of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the 1852 bestselling novel by Stowe that helped solidify anti-slavery sentiment in a divided nation, and display merchandise and material relating to theatrical productions—which Stowe did not create or endorse—that distorted the novel’s meaning. The center’s goal is to inspire people to learn about issues and act for positive social change.

As part of its mission, the Stowe Center sponsors discussions, programs, and the annual Stowe Prize, awarded to a work of fiction or nonfiction by a U.S. author that addresses a contemporary social justice issue and promotes understanding and empathy. In 2022, Dr. Clint Smith won the prize for his nonfiction work How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, which incorporates his visits to historic sites. The website has information about the June 1 dinner and author talk and the September 22 virtual event discussing the Stowe Center’s role teaching race history through the story of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Stowe Center

Born in Connecticut, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896) was one of the 11 children of Reverend Lyman Beecher, who gained fame by preaching against slavery in the 1820s after the Missouri Compromise. Activism was in the family DNA: sister Catharine Beecher opened schools and advocated for better education for women, and brother Henry Ward Beecher criticized slavery from his pulpit in Brooklyn in the 1850s; other siblings engaged with issues such as women’s suffrage. After 1832, while Stowe was living and teaching in Cincinnati, she saw an auction of enslaved people in Kentucky, a pivotal experience that strengthened her abolitionist beliefs.

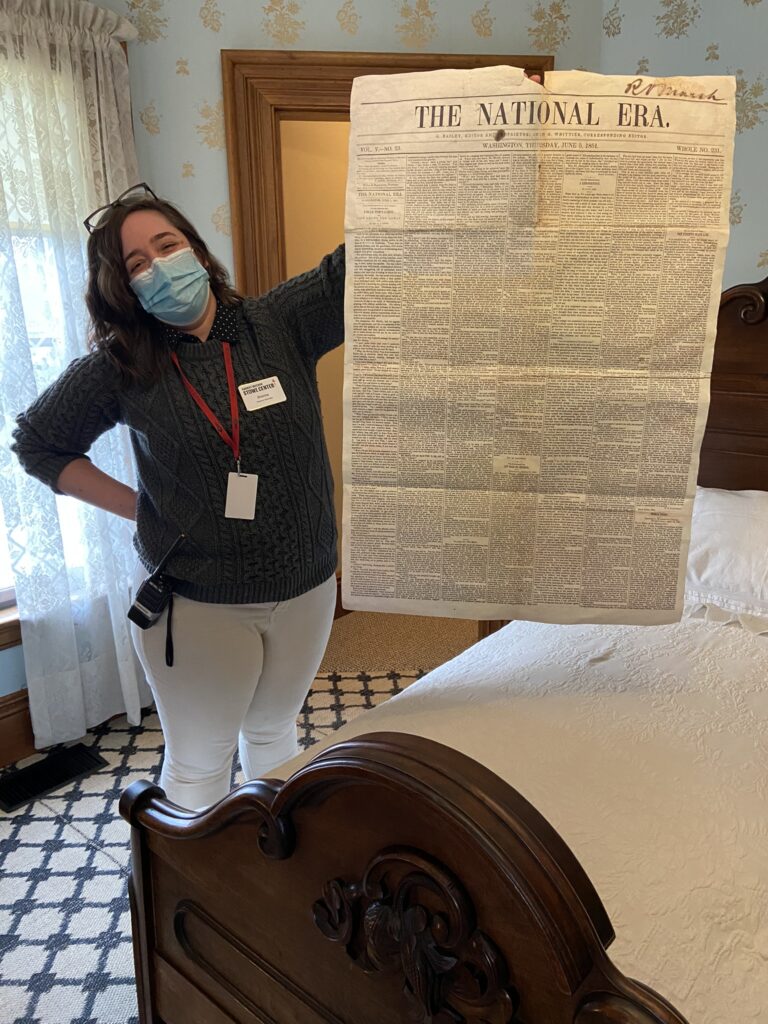

In 1836 Stowe married Reverend Calvin E. Stowe, an abolitionist and professor of biblical literature; the couple had seven children. By 1850, the couple moved to Brunswick, Maine, where Reverend Stowe taught at Bowdoin College. Disturbed by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required Northerners to help return escaped slaves, Stowe, then 40, wrote an emotional anti-slavery novel. It focused on a family of enslaved people who escape north and another family that becomes separated, including Uncle Tom, who is sold away from his wife and children. First printed in installments in The National Era, an anti-slavery newspaper, in 1851–1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in two volumes in 1852 and immediately became an international sensation and a bestseller for its critique of Southern justifications of slavery. About 300,000 copies were sold in the first year; only the Bible sold more copies in the United States in the 19th century. When Abraham Lincoln met Stowe in 1862, he reportedly said, “So, this is the little lady who made this big war.” Stowe published additional books and supported causes including education throughout her life, settling in Hartford from 1873 until her death in 1896.

In 1924, Katharine Seymour Day (1870–1964), Stowe’s grandniece and an artist and activist in the Progressive era, purchased the house, planning to restore it and honor the family. She gathered household items, family papers, and memorabilia. In 1941 Day incorporated the Stowe site as a foundation and bought the Gilded Age house next door that is now the Katharine Seymour Day House, home to the center’s library and collections storage.

When it opened in 1968, Stowe House was one of the country’s first Victorian house museums. In 1994, Norman Beecher, a Beecher descendant on the Board of Trustees, encouraged renaming the site the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center and refocusing public interpretation of the house on the ideas that inspired the extended family’s activism. Carrying through that suggestion, in 2018 Stowe House completed a restoration that included using the house to examine Harriet Beecher Stowe’s motivations for being anti-slavery and also helped visitors explore current social justice issues.

Exploring Stowe House and Beyond

Built in 1871, Stowe House is a comfortable Victorian Gothic house with colorfully decorated interiors. It was in the Nook Farm neighborhood, a progressive area that attracted writers including Mark Twain, whose house next door is well worth visiting. Early in the tour, visitors enter a gallery with photos of notable people from Frederick Douglas to Laura Bush and panels with their comments about Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The panels inspire discussion about what visitors know about Uncle Tom’s Cabin (a book now more talked about in history classes than read) and the fact that “Uncle Tom” has become a disparaging term and racial slur. Although Stowe framed Tom’s passivity as a Christian virtue and sign of his humanity, tastes and beliefs have changed; Victorian sentimentality reads as pity. Frederick Douglass, the Black abolitionist and social reformer, helped his friend Harriet Stowe with the novel and praised it for changing hearts and minds about slavery: “Its effect was amazing, instantaneous, and universal.” He also criticized aspects of it. James Baldwin, writing in 1949, criticized the novel for its “self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality,” an idea echoed by others.

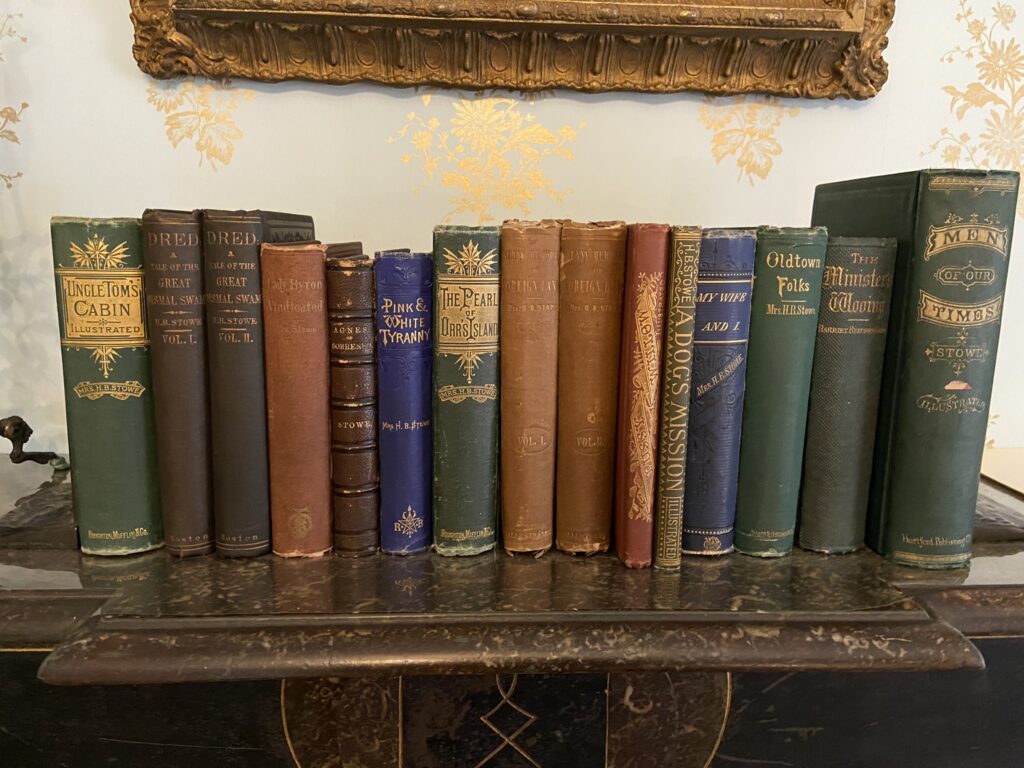

Remarkably, about 85 percent of Stowe House’s artifacts are original, creating a personal ambience. Examples of Stowe’s own artwork decorate the dining room and back parlor, as do student copies of Italian masterworks (she appreciated their affordability) from her European travels. A parlor table with photos of the family’s seven children is a reminder that the death of their 18-month-old son Samuel Charles from cholera in 1849 was one inspiration for writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe felt that her profound grief helped her empathize with the separation of enslaved families, such as the one she saw in Kentucky. A shelf of books by Stowe reflects her prolific career, which included 30 fiction and nonfiction books as well as articles and poetry. The front parlor, where Stowe’s guests might gather to discuss issues, now serves as a space for visitors to examine copies of 19th-century materials related to slavery (including selections from “The Anti-Slavery Alphabet” for children) and discuss their thoughts.

Upstairs, Harriet and Calvin’s bedroom shows evidence of a constantly busy writer. Stowe’s writing area overflows with papers and piles of correspondence. On the bed is a facsimile of The National Era, with part of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the front page. Stowe’s domestic arrangements, including her practical kitchen, reflect her interest in home management that would make life easier for women. She and her sister Catharine Beecher co-wrote an influential work on the subject, The American Woman’s Home: Principles of Domestic Science, published in 1869. Stowe also liked to garden; in summer the Stowe Center’s period gardens make a pleasant stroll.

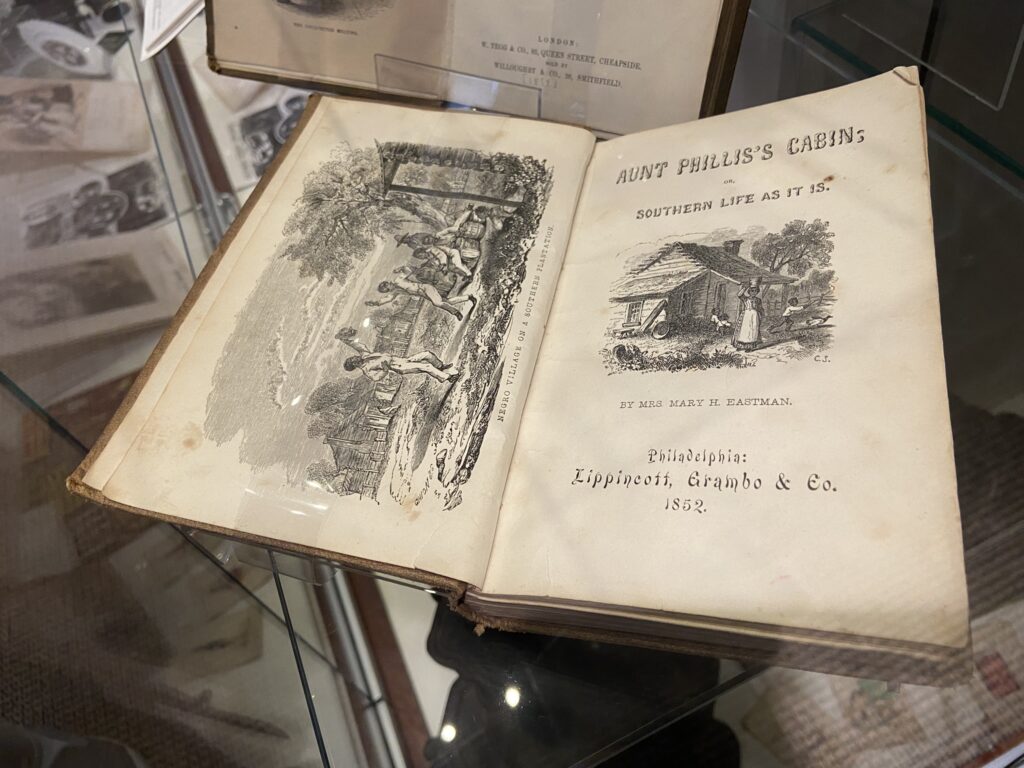

The “impact gallery” upstairs, displaying dozens of spinoffs from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, deserves hours of study. It presents period books, including “anti-Tom” pro-slavery fiction, as well as posters for shows based on the novel, and merchandise: dolls, porcelain pieces, music, even wallpaper (reproduced on the walls). Unfortunately, although early plays stayed true to the novel, the later plays and minstrel shows descended into caricature and damaging stereotypes. Stowe did not license any of this (copyright laws were different) and did not benefit from it.

The Stowe Center offers additional resources, in person and online, for students and adults. Its collections, the largest relating to Harriet Beecher Stowe, include 228,000 items—from furniture to rare manuscripts to books to images—that reveal the Stowe family’s life and times. The public can visit by appointment. Salons at Stowe are action-focused discussions on social justice topics relating to race, class, and gender; the discussions can be brought to schools or other locations. The pandemic created the opportunity for more outreach via virtual programs; check the online calendar and the multimedia gallery. The Stowe Center also presents programs with other institutions, including Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum and the Mark Twain House & Museum.

Side Dish

Connecticut has a state pizza trail, and New Haven–style coal-fired Neapolitan pizza is its most famous offering. Baked in an extremely hot oven, the thin-crust pies have a distinctive smoky taste and chewy crust. Frank Pepe Pizzeria Napoletana, based in New Haven but with a West Hartford location 10 minutes from the Stowe Center, has made its beloved pies since 1925. It features classics like the original tomato pie and white clam pie, and plenty of topping options. During summer’s tomato season, the fresh tomato pie is a must.

Linda Cabasin is a travel editor and writer who covered the globe at Fodor’s before taking up the freelance life. She’s a contributing editor at Fathom. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter at @lcabasin.

Wish I could post ALL this wonderful information on PINTEREST to my “BOOKS” board.

Loved the pictures of the house and interior. I have stayed in the NOLA, CORNSTOCK INN , where some of the ” UTC” was written.

My wife and I are prior owners of Coto deCaza Interiors, Inc in California. We love great exterior and interior design.

Loved your story…

Dr.& Mrs Tim Byron