One of America’s most widely recognized artists even nearly a half-century after his death, Norman Rockwell lived and worked in the Berkshires region of western Massachusetts for the last 25 years of his life. His legacy is preserved and celebrated there in the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, which holds the world’s largest collection of his original artworks.

From the first decades of the 20th century through the 1960s, Norman Rockwell was one of America’s best-known illustrators, his images of American life seen in tens of thousands of households each week. He was still in his teens when he became art director for Boy’s Life and went on to illustrate other publications for young readers, and later for magazines that included Life and Country Gentleman.

When he was only 22, he painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, beginning a 47-year relationship that would produce 321 Rockwell cover illustrations that capture forever the essence of American small-town life in the mid-20th century.

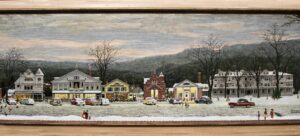

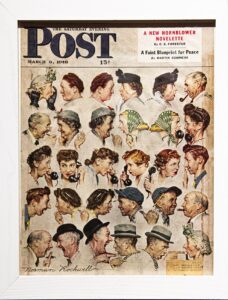

His ability to convey nostalgia and the ideals of American life through gentle humor and perceptive characterizations of ordinary people made these magazine covers appealing to everyone. The stories each painting told in the faces and detailed settings were immediately clear, and readers looked forward to each issue as much for the cover as the contents. Among the highlights of the museum’s collection are favorites from his Saturday Evening Post covers. In a similar vein, and another of the museum’s highlights is his Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas.

By 1963 Rockwell’s concerns for social issues led him to move away from these small-town vignettes and turn his talents to other interests. He ended his nearly half a century with The Saturday Evening Post and began painting covers for Look magazine, documenting subjects such as civil rights and fighting poverty.

The success of his wartime paintings of The Four Freedoms, which had raised more than $130 million in War Bonds when they toured the United States during World War II, showed how his images could be a force for change. His direct, almost editorial, style in these paintings for Look carried some powerful messages.

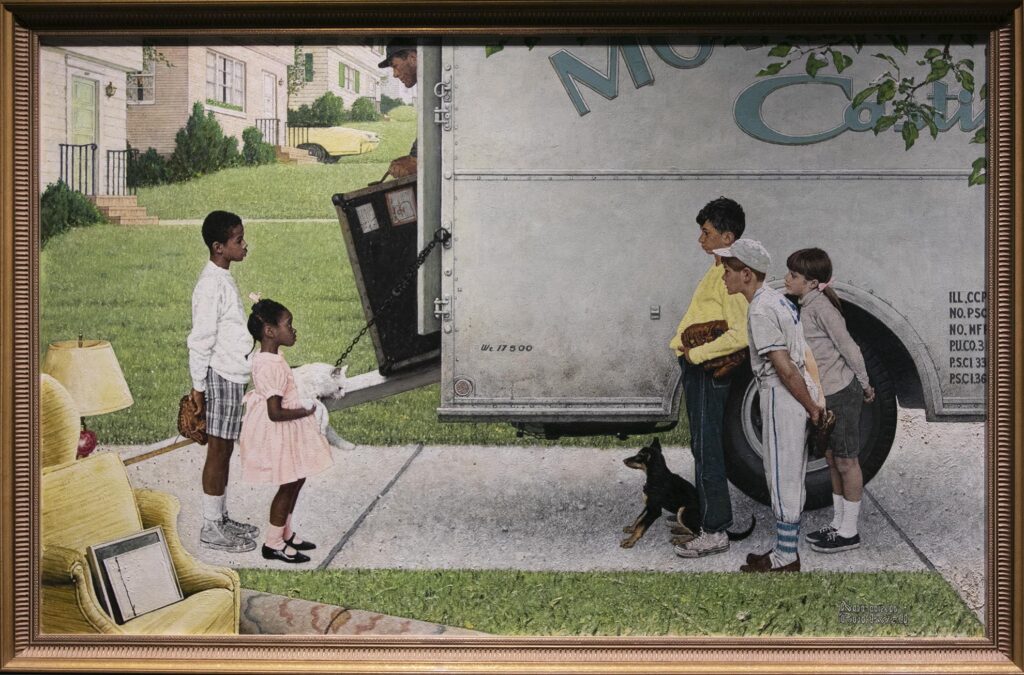

Freed from The Saturday Evening Post’s rule that people of color could only be portrayed in service roles, he tackled segregation with two of his most dynamic works. His first cover for Look was The Problem We All Live With, a dramatic image of a tiny African-American girl walking between U.S. marshals on her way to an all-white school. A later Look cover in 1967, Negro in the Suburbs, again chooses children, this time to document the tensions of integrating neighborhoods. The large original painting, on display at the museum, is as powerful today as it was on a magazine cover in 1967.

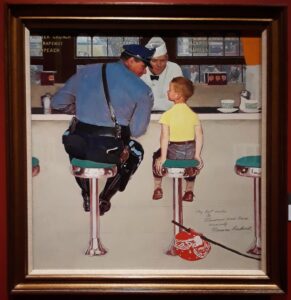

The notion that illustration is merely the pictorial retelling of someone else’s story falls flat in the face of Norman Rockwell’s magazine covers and posters. Each of his paintings tells its own story – Black children moving into a White neighborhood, a policeman in a diner with a small runaway boy, a World War II serviceman home for Thanksgiving. Many of them chronicled moments of everyday life, with themes expressing the qualities of small-town America: a little boy with his puppy at the Vet, children playing baseball or sledding, people raking leaves, voting, fishing.

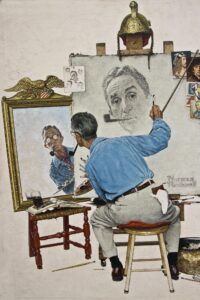

Rockwell’s impish sense of humor shines through in works such as his triple self-portrait and Chain of Gossip, a series of faces in pairs hearing and repeating a juicy morsel. Another of his multi-portrait works is a family tree, showing prosperous, self-satisfied people at the top, all traced back through the generations to a pirate ancestor.

Norman Rockwell’s portraits of American presidents and candidates were a staple of his years with The Saturday Evening Post – a smiling Eisenhower, a pensive John F. Kennedy, and a portrait of Lyndon Johnson that Johnson famously called “the ugliest thing I ever saw,” even though Rockwell admitted to a bit of cosmetic adjustment by trimming a bit off LBJ’s sagging jowls. He captured their personalities, often in multiple views on the same canvas.

Although these were created for magazine covers, and as such, are considered illustrations, they provide the same lasting artistic memorial as Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington or the portrait of Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley.

Many of Norman Rockwell’s works shown in the museum are icons of their time — his Four Freedoms posters, the policeman and boy sitting in a diner in The Runaway, and the dynamic Grand Canyon Dam, done for the Bureau of Reclamation.

The museum’s more than 700 Rockwell works include fascinating insights into his working process, in exhibits that document how he approached his subject matter. Some show his detailed photographs of models, the charcoal sketches he made from them, his preliminary drawings and the final painting, shown with the published magazine cover. Even for visitors who are not artists themselves, this is a fascinating glimpse into an artist’s working methods.

More insights into his creative process and environment are found in Rockwell’s studio, adjacent to the museum. The small building where he worked after moving from his previous home in Vermont, was moved here when the museum opened, and is equipped just as he left it.

The museum’s lower level shows a short film on Rockwell’s life, and has three walls covered in the chronological series of his Saturday Evening Post covers. Not only is it interesting to follow their 47-year progression, but the sheer number of them is staggering.

Along with Rockwell’s own work, the museum shows works by his contemporary and earlier American illustrators, often in rotating exhibits that feature a particular artist or school. Regular exhibitions of works by contemporary illustrators bring a lively 21st-century dimension to the collections.

Special exhibits keep the museum’s galleries fresh and exciting to repeat visitors, such as the most recent one, Reimagining the Four Freedoms, mounted by this museum and returned here following a nation-wide and international tour. For this special exhibition, artists were asked to consider what freedom means today, giving a contemporary interpretation of the four freedoms Franklin Roosevelt declared to be human rights in his 1941 Inaugural Address. These were immortalized in paintings by Rockwell in 1943.

This and many other special exhibitions live on after the actual works have left, in the museum’s outstanding library of virtual programs. Two of these feature recent exhibits of works by illustrator Frank Schoonover and the work of Gregory Manchess, done for his book Above the Timberline. Others in the extensive library of virtual programs include Norman Rockwell in the Age of the Civil Rights Movement, and video presentations that illustrate a variety of themes through the museum’s collections.

Some feature artists, such as Jeff Mack, who reads from his new book, Just a Story, and cultural historian Skylar Smith, who invites viewers to draw along with him as he creates drawings inspired by early illustrations. Hands-on instruction programs, such as The Sketch Club feature everything from step-by-step lessons on sketching or painting in acrylics to mask-making. The Sketch Club offers Viewers anywhere can enjoy the virtual tours and creative sessions free of charge.

Side Dish

The Berkshires have long drawn artists, musicians and writers who have created a rich cultural climate and heritage. Homes of Herman Melville, Edith Wharton, and the home and studio of Daniel Chester French welcome visitors. This is also a thriving center for contemporary artists, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra performing here at Tanglewood each summer, and galleries showing local and international artworks.

Foremost among these is Schantz Galleries on Elm Street in Stockbridge, featuring works of art in glass by some of the world’s finest artists, including Dale Chihuly and other internationally recognized artists in all glass techniques.

Step back a couple of centuries for candlelight dinner at Old Inn on the Green, in nearby New Marlborough, Massachusetts. Candles and the fireplace fill the dining room of this historic inn with a warm glow, and the menu has earned the inn the reputation of one of New England’s best restaurants. Guest rooms are equally charming, with fireplaces, pine paneled walls and antique furnishings.

By Barbara Radcliffe Rogers and Stillman Rogers

Barbara Radcliffe Rogers

Europe Correspondent, Planetware

Luxury Travel Editor, BellaOnline

Features, Global Traveler Magazine

https://worldbite.wordpress.com

Stillman Rogers

World Correspondent, Destinations

Photographer, Planetware.com

1 Comment