In the hierarchy of artists, illustrators have been never been accorded the standing of the so-called fine arts. And yet most people’s first and most enduring acquaintance with art has been through illustrations. Think of Winnie-the-Pooh, Peter Rabbit, Alice in Wonderland, and the other characters we first met on the pages of childhood books.

Before the advent of the ubiquitous clip art that now serves more to fill in blank spaces than to illustrate the text, pictures were an integral part of literature. Our mental images of Scrooge and other characters from the classics come from illustrations, and they even shape our pictures of historic people and events. Not always accurately, as in the case of the Pilgrims’ landing in Plymouth, but enduringly.

Without getting into the age-old debate over the differences between art and illustration, one thing is clear: illustrators have never been accorded the same status as those whose work is destined only to hang in galleries or decorate homes and offices. Somehow the fact that a work is useful diminishes its perceived value. The theory is that an illustrator merely reinforces the message of the written work with a visual prompt, while an artist creates or originates the message itself.

Whether or not this reasoning bears merit, museums rarely accord the works – even the originals — of illustrators the same prestige they would give an oil painting of equal artistic merit. This makes the Delaware Art Museum, in Wilmington, a refreshing oasis for those who appreciate the illustrator’s art.

From its very beginning, the art of illustration was the focus of the museum’s collections. It began in 1912 as the Wilmington Society of the Fine Arts with a collection of more than 100 paintings, drawings, and prints by Wilmington artist Howard Pyle. After his death in 1911, his friends and former students – many of whom were by then famous artists themselves – wanted to honor him by founding a museum “to promote the knowledge and enjoyment of and cultivation in the fine arts in the State of Delaware.”

A few years later the collections doubled with the gift of more than 100 of Pyle’s pen and ink drawings. The collections were shown in special exhibitions and in rooms of the Wilmington library. In 1931 the Society was offered the Bancroft collection of Pre-Raphaelite works, the largest collection of Pre-Raphaelite art and manuscripts outside the United Kingdom, along with 11 acres in Wilmington for a permanent museum.

Today the Delaware Art Museum holds more than 12,000 objects, housed in a campus that includes a nine-acre sculpture park and a library. Adding to the Howard Pyle collection are works of his students and other major illustrators, and although the museum’s holdings encompass several other collections, it is best known for its American illustration and British Pre-Raphaelite art.

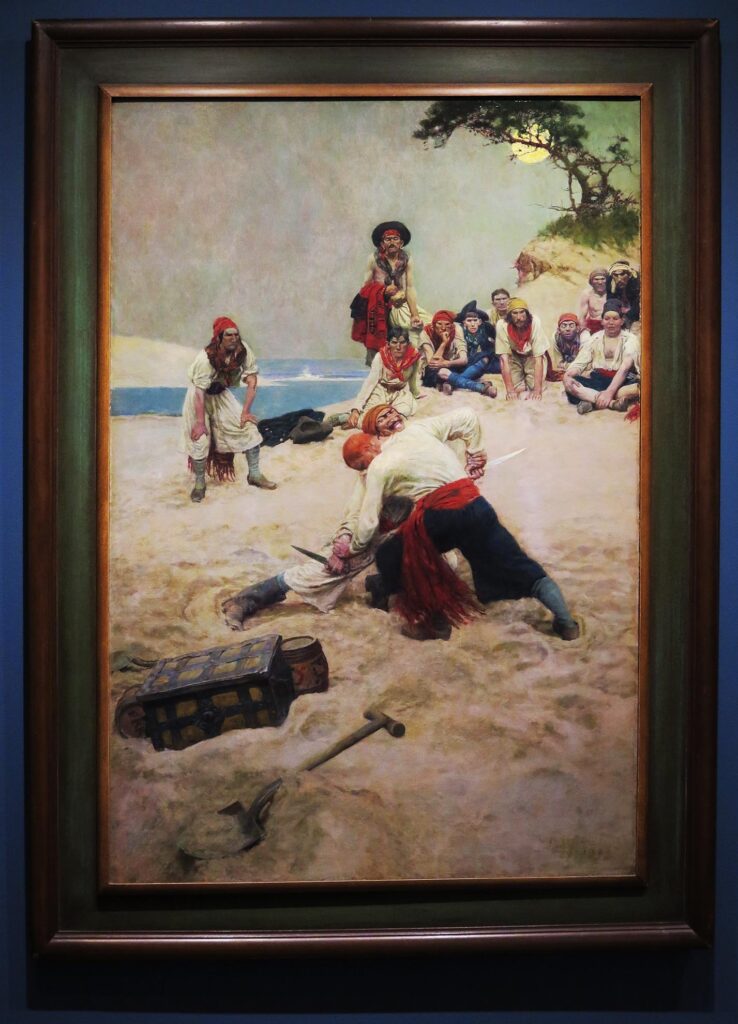

Pyle was the best-known American illustrator of the early 20th century, a time when magazines such as Harper’s Weekly, Collier’s and Saturday Evening Post were read in hundreds of thousands of American homes each week. In addition to magazines, Pyle is more enduringly known for his illustrations of popular books by Mark Twain and Robert Lewis Stevenson, especially his depictions of pirates for Treasure Island.

One of the many appeals of the museum is the excellent interpretive information, putting the works in the context of their time and drawing their relevance into the present. The interpretive panels for Pyle’s Treasure Island illustrations, for example, point out that his images of pirates formed the popular vision of how pirates looked and dressed. He researched period clothing and let his imagination and his ability to capture the drama of a story do the rest.

Pyle is also known for his atmospheric drawings, etchings and paintings of mythological figures and scenes from tales of medieval chivalry. His dramatic images of Sir Galahad and the Knights of the Round Table remain the classics of the genre, as do his illustrations for The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, the original 1883 edition of which remains in print to this day.

His ability to convey the ethereal settings of mythology is shown dramatically in the murals he painted for his family’s home in Wilmington. The nine panels, two of which are entitled The Genius of Art and The Genius of Literature, surrounded a room, which has been replicated in the museum with the original murals. In the first of these, female figures in diaphanous gowns celebrate in a flower-decked pastoral setting; in the second a muse plays a lyre to a small group of listeners. Other scenes carry out this theme of celebrating the arts.

Alongside Pyle’s paintings, books, etchings and drawings are works of other American illustrators, including Maxfield Parrish, Norman Rockwell, N.C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover and other illustrators whose images are still familiar ones today.

Charles Dana Gibson created the Gibson Girl, the iconic woman of the turn of the 20th century; Thomas Nast is known for the modern version of Santa Claus and for Uncle Sam. John Held, Jr. shaped our image of flappers and the Jazz Age, and J. C. Leyendecker, principal cover artist at Saturday Evening Post for half a century, created the familiar symbol of the New Year Baby.

The other premier collection of the Delaware Art Museum is the country’s largest and most significant group of works by the Pre-Raphaelites, including works by Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway, William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. From the same period are jewelry and metalwork in the English Arts and Crafts style.

American artists of other genres and periods are represented by works of Frederic Edwin Church, Winslow Homer, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Edward Hopper, Reginald Marsh, Andrew Wyeth and others.

Vying with the room full of Pyle murals for the most dramatic exhibit in the museum is the arrangement of brilliant glass flowers by Dale Chihuly. Each one several feet in diameter, these stylized flowers are positioned in front of a picture window above the atrium, creating a dazzling picture above the door for those approaching the building. A walkway between the building’s two wings allows a close-up look at their sweeping lines and brilliant colors.

Outside in the Copeland Sculpture Garden are 20 large three-dimensional works, a collection begun in the mid-1960s with Domenico Mortellito’s Protecting the Future, a commentary on pollution. Other highlights are Tom Otterness’ 13-foot Crying Giant and Three Rectangles Horizontal Jointed Gyratory III by George Rickey, constantly moving in the slightest breeze. There are several fine examples of abstract metal sculpture and a labyrinth 80 feet in diameter, built from Delaware River rock.

From its inception, the Delaware Art Museum’s mission has been to highlight and promote local art and artists and to serve the local community and connect people with art. Along with its permanent collections and changing exhibits, the museum sponsors concerts, films and other cultural events and offers a program of art experiences, classes and workshops for children and adults.

Rising to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum is offering a regular schedule of virtual tours and experiences, such as the Virtual Art Chat on Stained-Glass Windows, an hour-long interactive exploration of the stained-glass windows owned by the donor of the museum’s Pre-Raphaelite art collection, Samuel Bancroft.

Children can see characters from the museum’s paintings come to life on the screen with storyteller Jeff Hopkins, who tells and illustrates stories as they watch and draw along with the videos. Pirate and Mermaid Adventures will be available through Jun 30, 2021; the programs are free, and available through the museum website’s family page.

Side Dish

Wilmington is at the southernmost end of the Brandywine Valley, a 20-mile corridor that packs a breathtaking array of art, history, lavish estates and gardens. The route north to Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, is designated as the Brandywine Valley Scenic Byway and it connects the Nemours Estate, Winterthur Museum and Gardens, Longwood Gardens, the Brandywine River Museum of Art, and the vast industrial estate at Hagley Museum.

About midway, the charming Fairville Inn in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, is well located as a quiet base for exploring these gardens, museums and estates. This B&B features large guest rooms in the main house and suites in the adjacent Carriage House. A proper tea time with fresh-baked sweets and full hot breakfast are included.

A five-minute drive from the inn is Buckley’s Tavern, serving well-prepared American dishes and seafood specialties (the shrimp-and-grits are excellent) in an 1800s house.

By Barbara Radcliffe Rogers

Europe Correspondent, Planetware

Luxury Travel Editor, BellaOnline

Features, Global Traveler Magazine

https://worldbite.wordpress.com

1 Comment