The National Archives has just undergone a major face-lift—a $40-million, AI-driven reimagining—perfectly timed for America’s 250th anniversary in 2026. For generations, this stately institution has been a must-visit destination in Washington, D.C., home to the nation’s founding documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, displayed in the dusky, echoing Rotunda at the building’s heart. Those iconic texts remain—soon to be joined by two additional pillars of American democracy in March 2026: the 19th Amendment and the Emancipation Proclamation, showcased in newly designed custom cases.

The real surprise, however, awaits just next door. There, you’ll find “The American Story,” a bold new salute to the nation’s history. Spanning 10,000 square feet, nine immersive galleries trace the evolution of the United States from its earliest beginnings to today. For the curators, this challenge was formidable: with 13.5 billion photographs, documents, films, and maps in the Archives’ care, how do you create an experience that resonates with every visitor?

The answer lies in personalization—powered by artificial intelligence.

In these new galleries, sophisticated technology tailors the Archives’ vast holdings to individual interests—whether World War II, gardens, national parks, diplomacy, holidays, or countless other themes. The result is an ocean of history distilled into a curated deeply personal digital journey. Paired with rotating displays of handwritten letters, fragile documents, original photographs, and other treasures throughout the space, the experience is unlike anything the Archives—or any other museum in Washington, D.C.—has offered before.

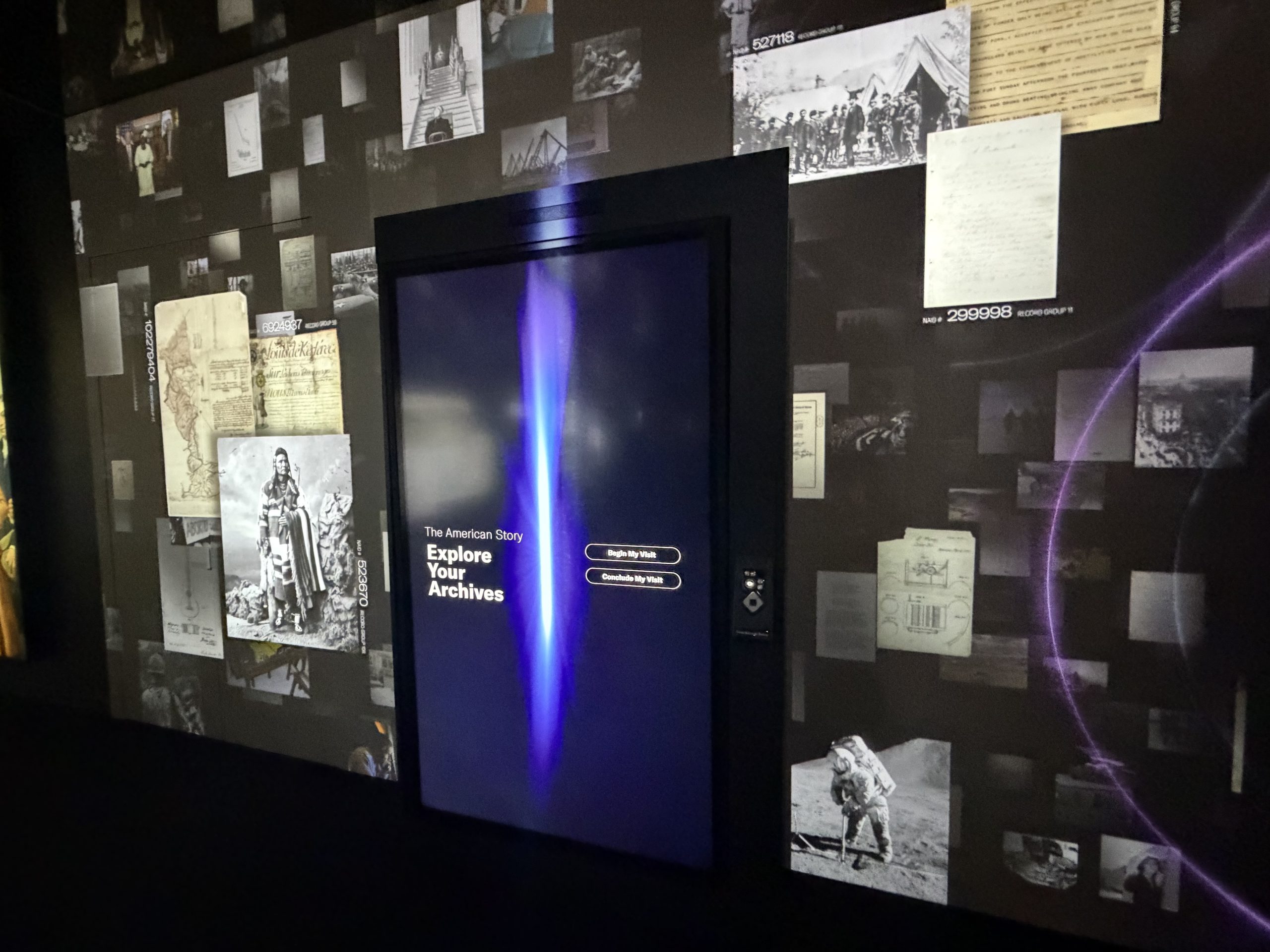

Introductory Gallery: Explore Your Archives

You begin your visit to “The American Story” by entering the dimly lit Introductory Gallery, where projected photos, maps, and handwritten records rush across the far wall—glimpses of American moments, mostly B&W, frozen in time: a rocket launch, WW2 soldiers, a women’s suffrage parade, letters signed by Abraham Lincoln, hand-sketched maps of Washington, D.C., and hundreds more.

Along each side of the room stand eight glowing AI-powered portals, where the experience begins. Using a free QR-coded ticket—reserved in advance or handed to you at the door—you select the themes that interest you most, along with the types of records you prefer: photographs, maps, artifacts, or documents.

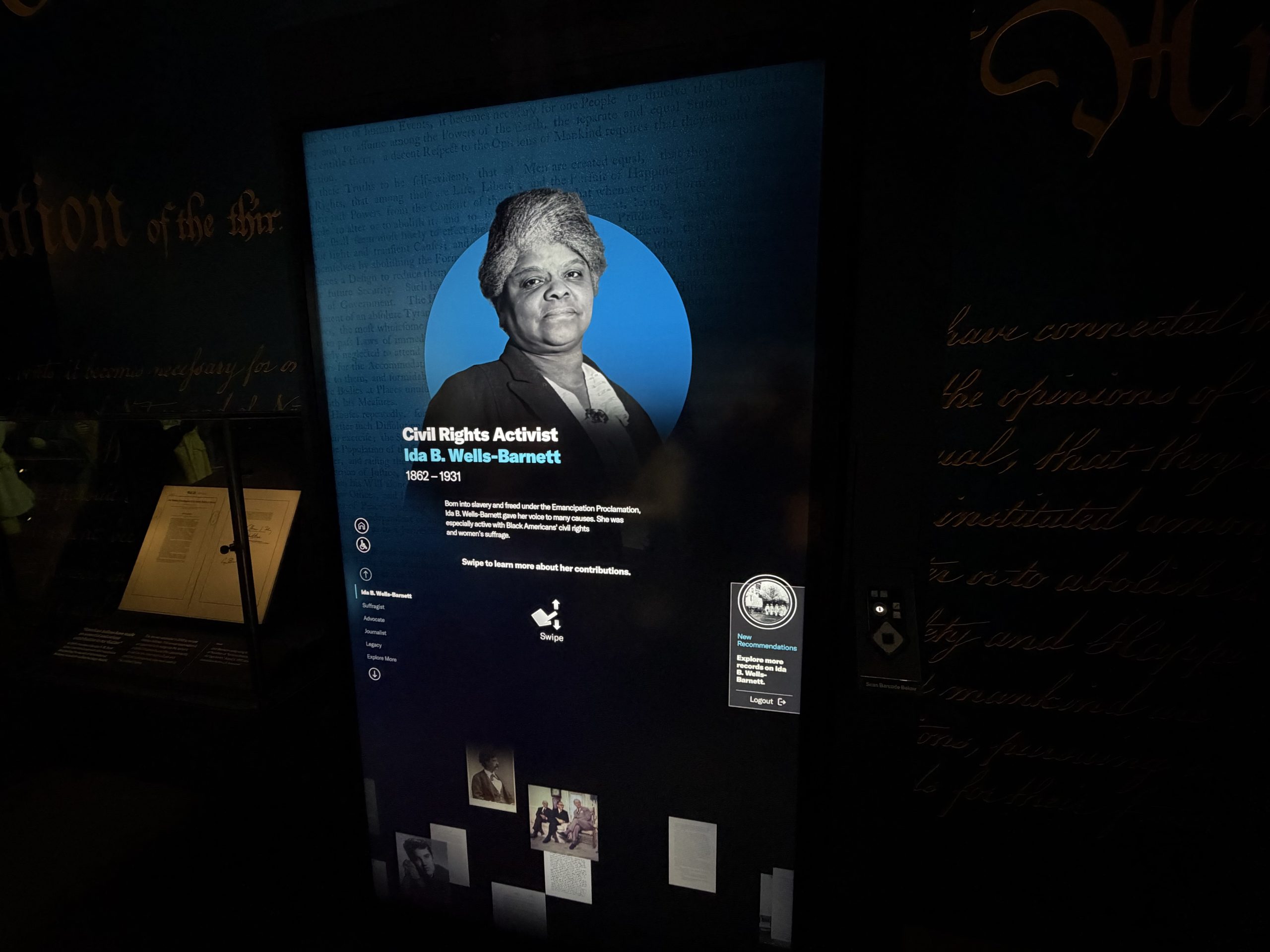

Deeper in the exhibition, your QR code will access interactive, AI-powered kiosks sprinkled throughout, offering three distinct layers of history: two curated by the National Archives, and a third tailored to your personal interests, weaving your selections directly into the nation’s story. My pick: Women’s Suffrage.

“Chartering Freedom” Gallery

This gallery focuses on the country’s founding documents that guarantee Americans’ freedoms: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Emancipation Proclamation. The centerpiece is the engraved copper printing plate created by William J. Stone in 1823 to ensure the Declaration would physically live on—just 50 years after it was signed in 1776, the original document was already fading. A print made from the plate is displayed alongside.

Using your QR code, you can also deep dive into the records at several different AI-generated kiosks, including one focusing on “Exceptional Americans in the Records.” Among the many individuals to choose from, based on my curated preferences, I got to know Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Born into slavery in 1862, she played an important role in Black Americans’ civil rights and women’s suffrage. One story talks about how she kept her name after marriage in 1895—becoming one of the first American women to keep her maiden name while adopting her husband’s.

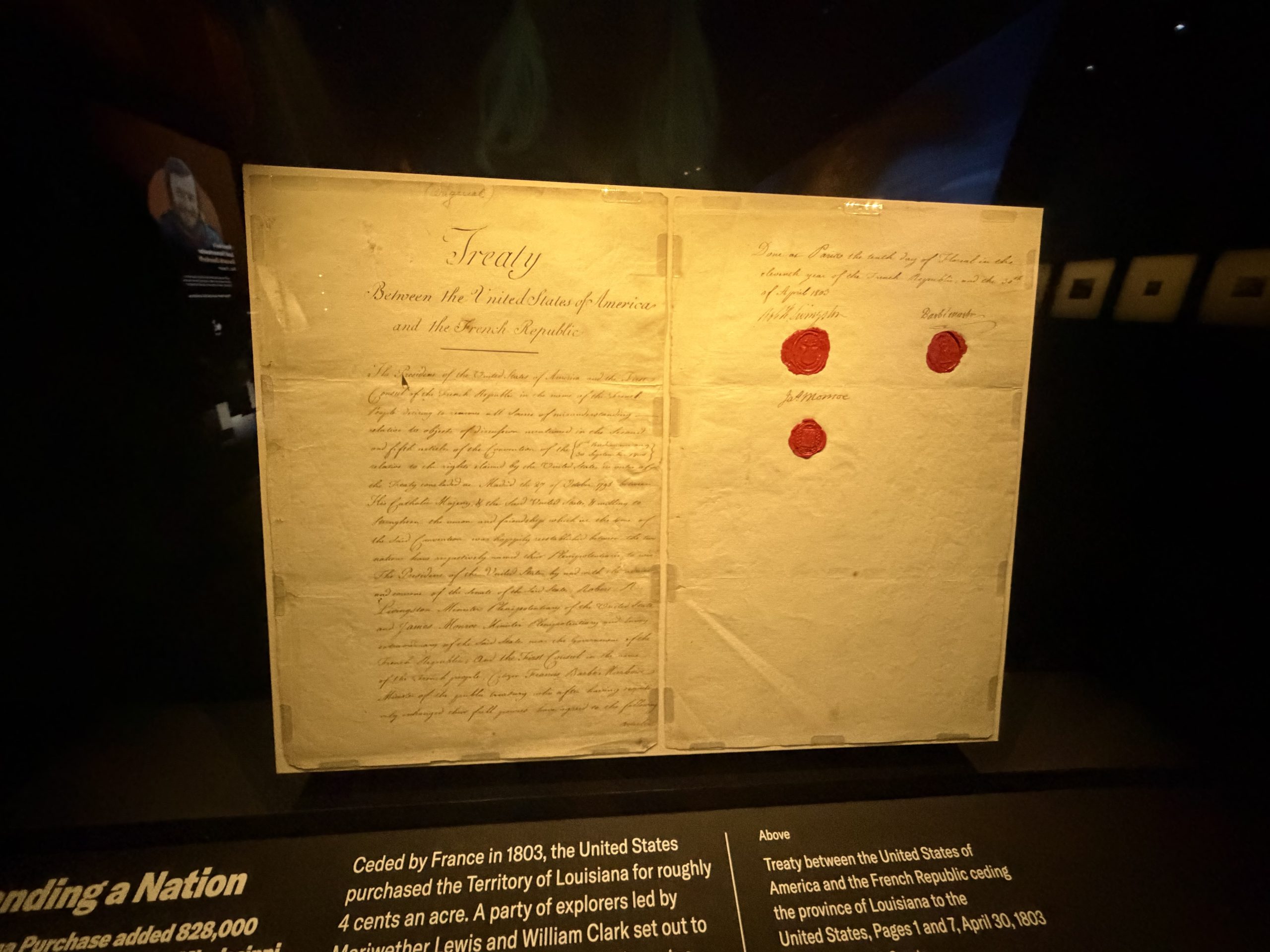

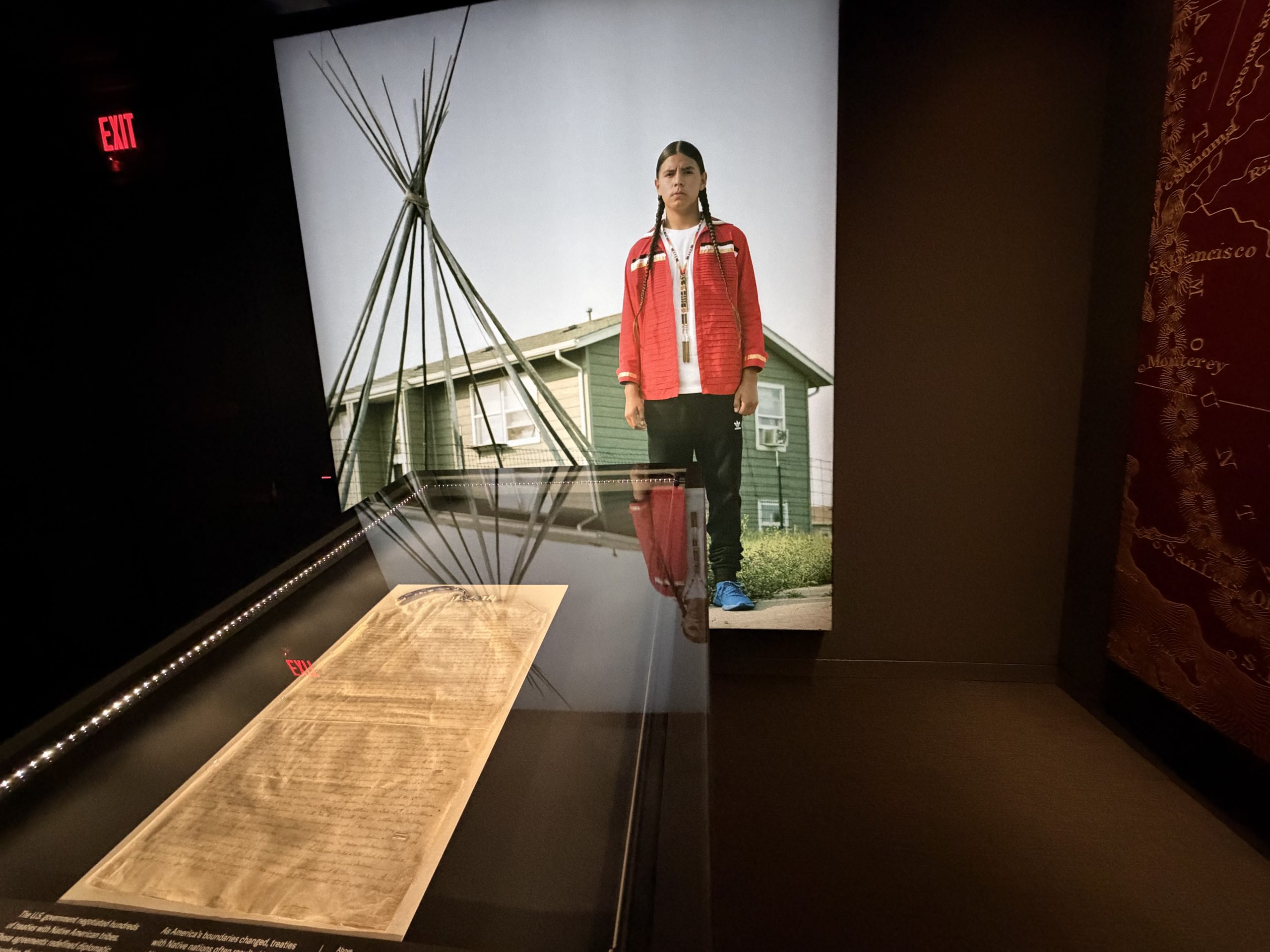

“Land & Home” Gallery

The push westward by the United States fueled stories of expansion, trade, promise—and conflict—as European settlers moved onto lands already inhabited by Native peoples. This gallery confronts complex truths about what it means to “make a home” on contested ground. At the heart of it are pages 1 and 7 of the Louisiana Purchase, the 1803 agreement that transferred 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River to the United States, forever reshaping the map.

A rotating display of original Native treaties underscores how the nation was redefined through negotiation and coercion. Hundreds of agreements—each one altering diplomatic relations, questions of sovereignty, trade, and land title—still shape present-day conversations. On my visit, the featured document was an 1829 treaty signed at Prairie du Chien between the United States and the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), negotiated in what was then Michigan Territory.

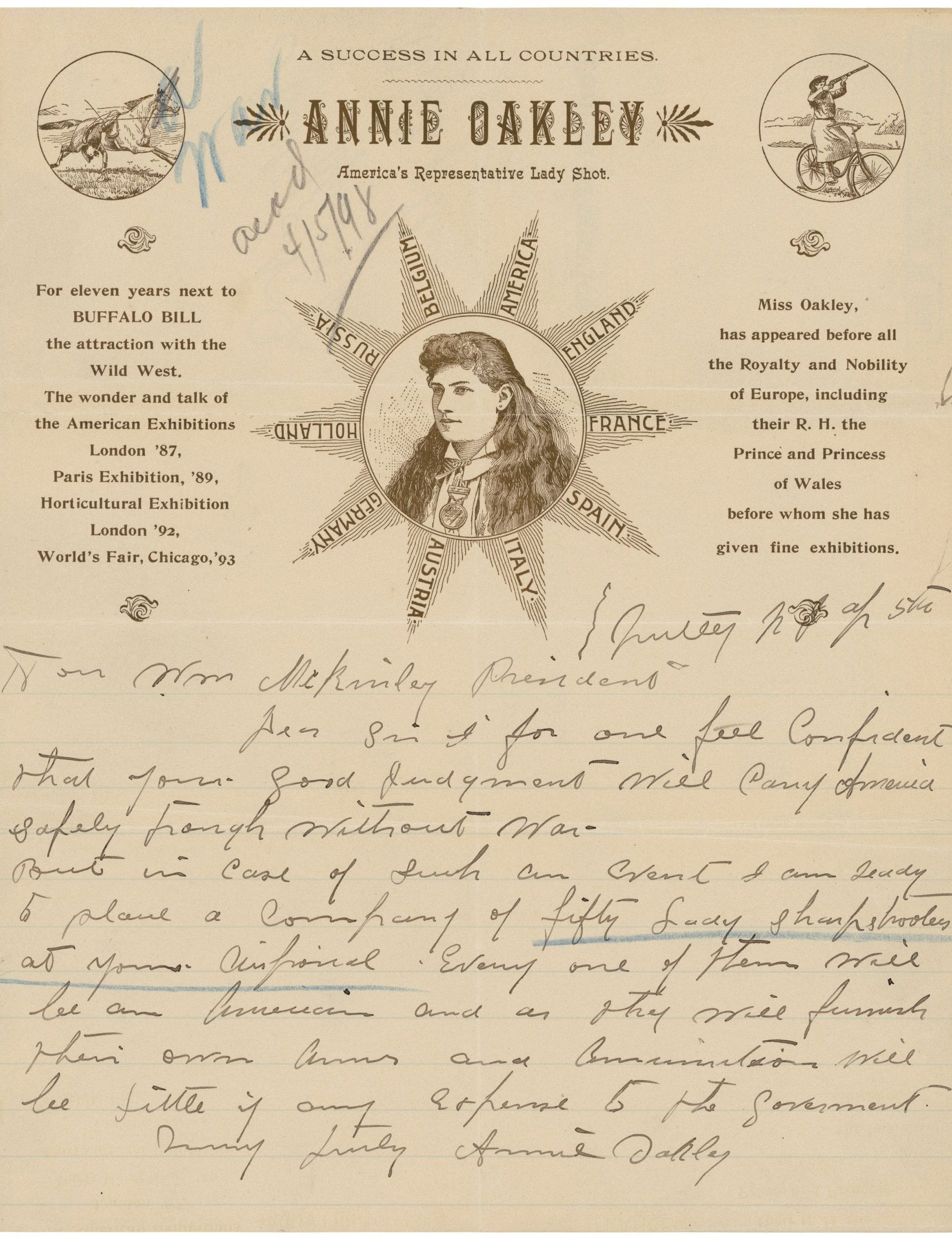

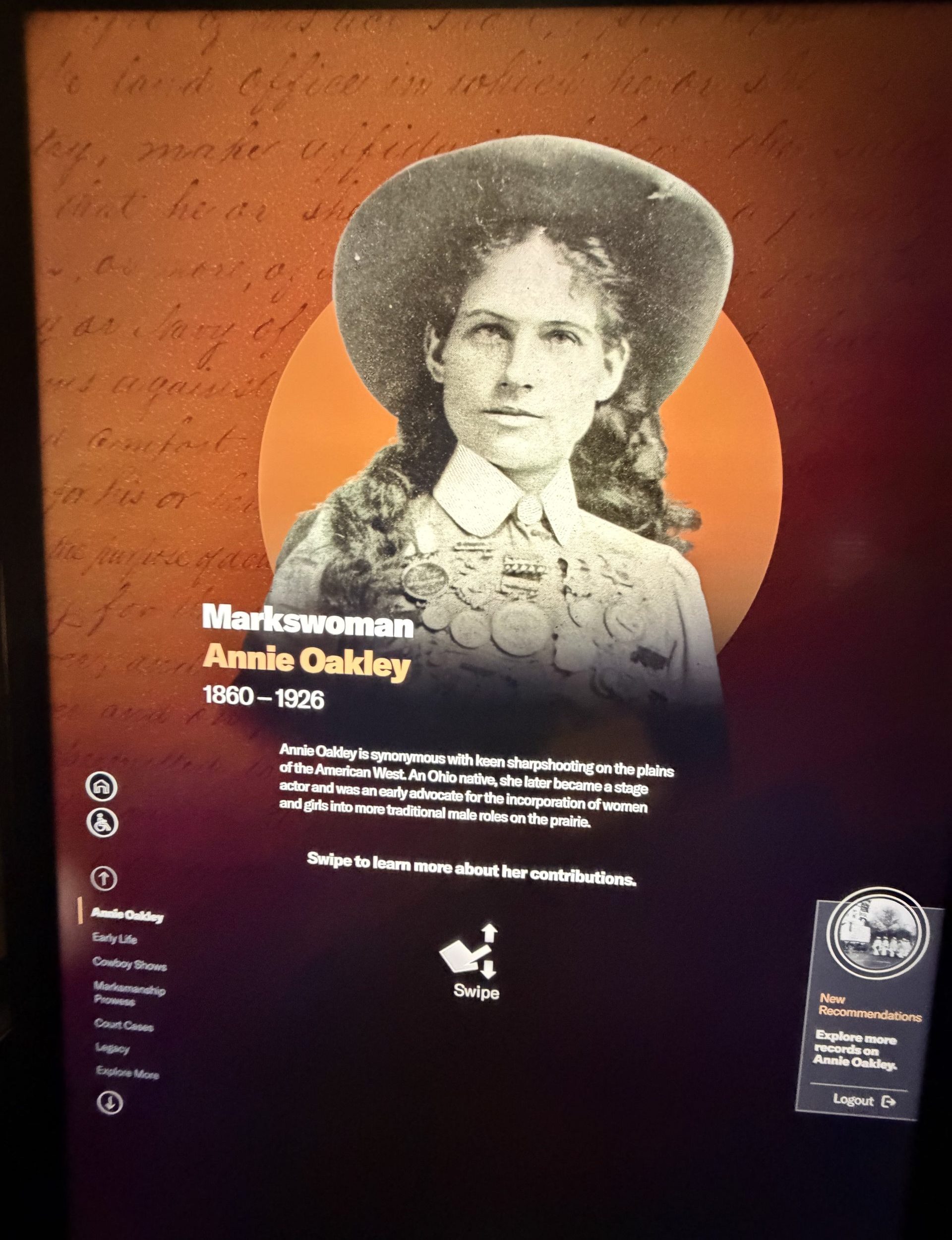

The gallery also introduces AI-generated kiosks showcasing “Exceptional Americans in the Records,” sharing personal stories from the frontier and beyond—among them Congressman Davy Crockett, sculptor Augusta Savage, and legendary markswoman Annie Oakley. I selected Oakley, and among the artifacts surfaced was a handwritten letter she addressed to President William McKinley, dated April 5, 1898, boldly volunteering “a company of 50 lady sharpshooters at your disposal” should war break out with Spain.

“Picturing A Nation” Gallery

A side gallery displays a selection of landscape photographs shot by Ansel Adams for a federal photographic commission program. Every few months, the display refreshes with work by other notable photographers, such as Depression-era documentarian Dorothea Lange and Yoichi Okamoto, the official White House photographer under Lyndon B. Johnson.

“A More Perfect Union” Gallery

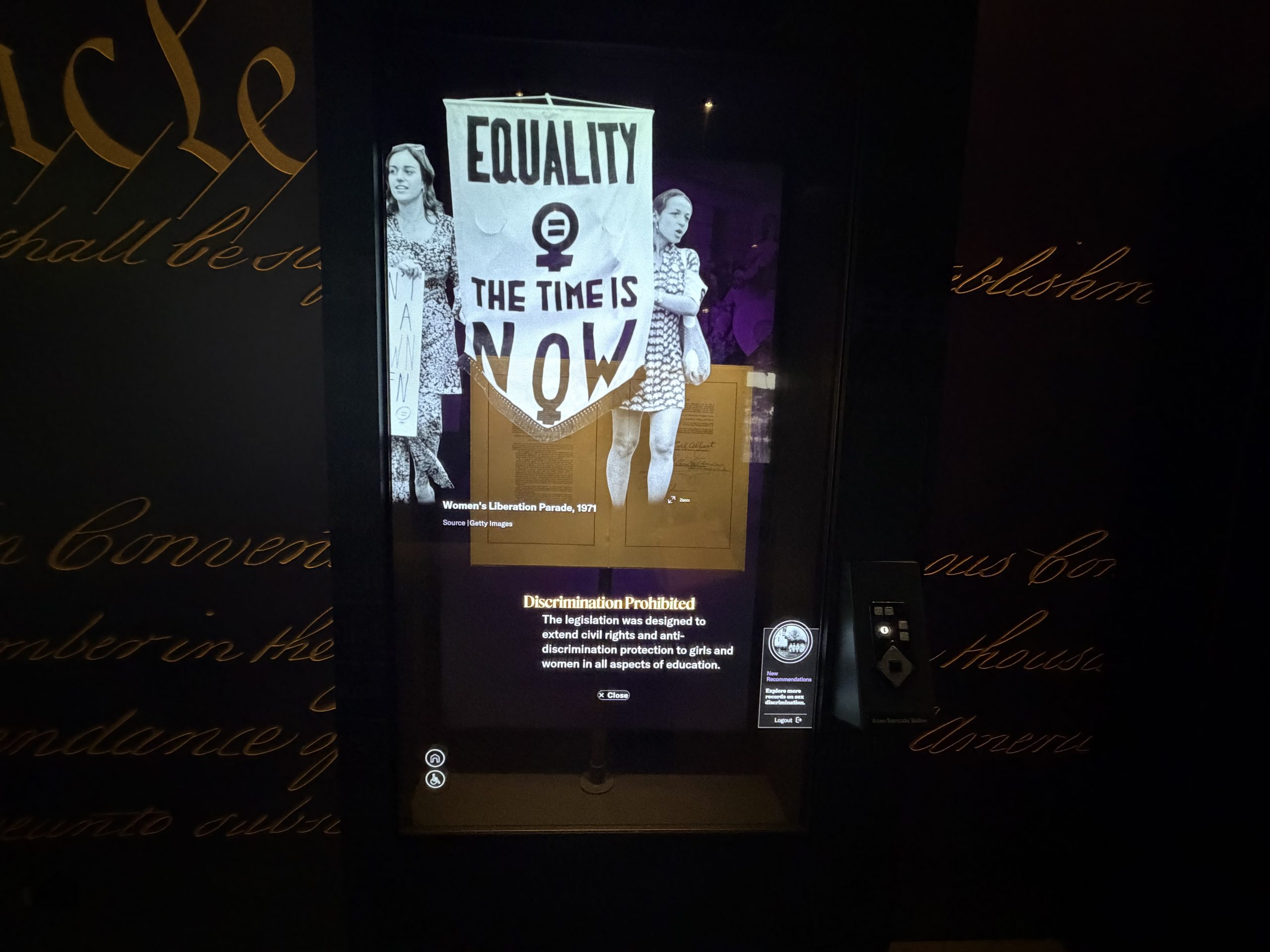

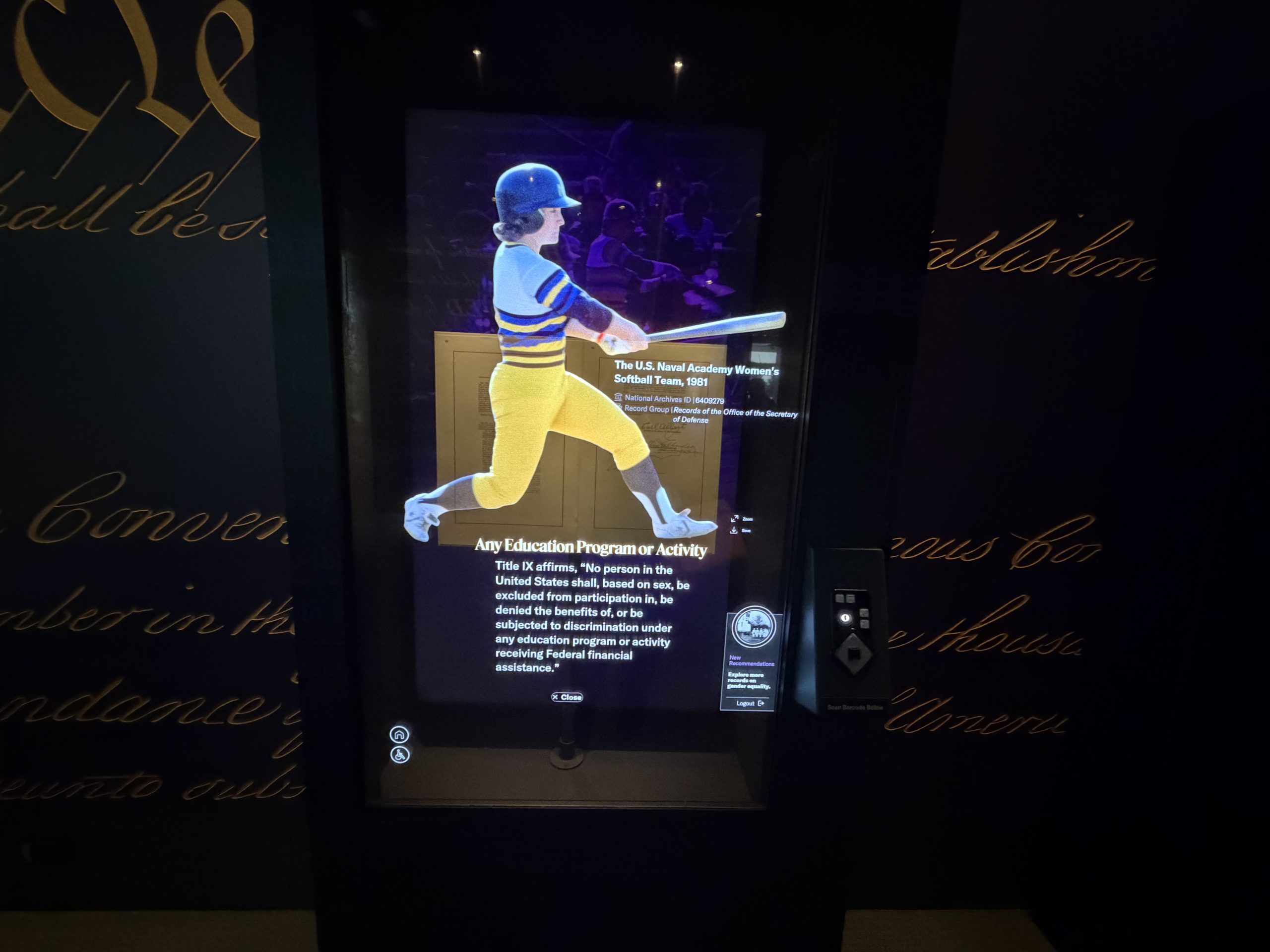

At the heart of this gallery is the U.S. Constitution, presented not as a relic but as a force that drives how the country works. One of the AI-generated kiosks breaks down the Constitution’s system of checks and balances, showing how a single signed law can steer the country’s direction, affecting both policy and everyday life. Then comes the showstopper: George Washington’s own annotated copy of the Constitution, opened to the first page of his handwritten notes. From there, you follow the Constitution’s influence across major milestones, including Title IX, part of the Education Amendments of 1972 that revolutionized education by banning gender discrimination in federally funded schools.

One of the stories I tapped into at the interactive kiosk spotlighted the 1981 U.S. Naval Academy Women’s Softball Team—trailblazers in a pivotal year for women’s sports. Their season unfolded just as the NCAA began overseeing women’s athletics for the first time (1981–82), a shift that helped reshape college sports and expand opportunities for female athletes across the country.

The Common Defense Gallery

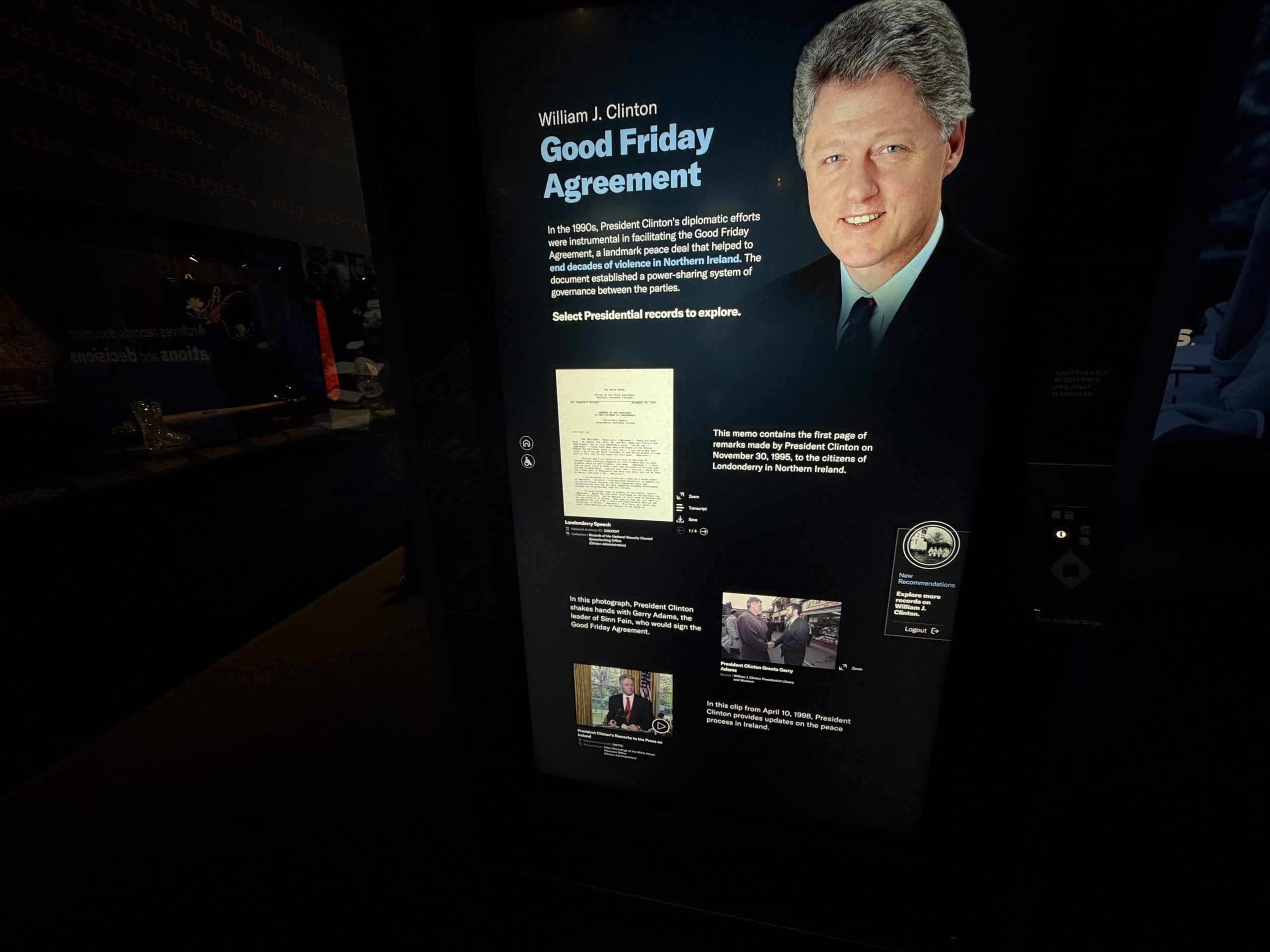

Split into two sections—”Conflict & Crisis” and “Art of Diplomacy”—this gallery explores how the United States has been defended, protected, and represented on the world stage. The exhibition that showcases defense draws on records from every branch of the military except Space Force (coming soon), revealing moments of courage, sacrifice, and strategic decision-making.

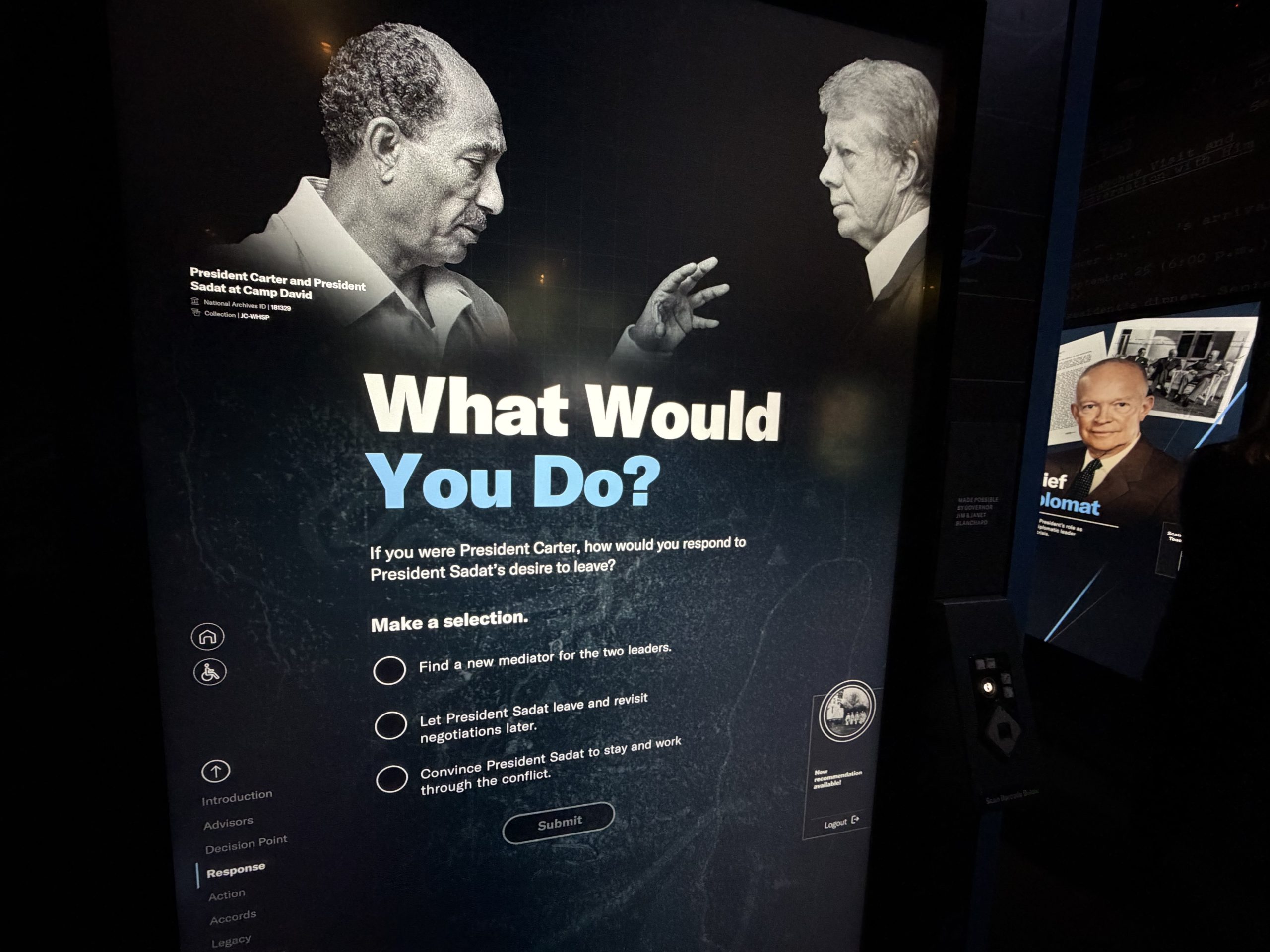

On the diplomacy side, one of the most compelling features is interactive kiosks that place you in the commander-in-chief’s seat during pivotal moments in history. You might step into Franklin D. Roosevelt’s shoes after the attack on Pearl Harbor, stand beside George W. Bush on September 11, or weigh options with Lyndon B. Johnson after the Gulf of Tonkin incident. Each incident lets you listen to advisors, examine digitized primary documents, and decide how you would respond. It’s especially gripping to see FDR’s typewritten “Day of Infamy” speech covered with his handwritten edits.

The gallery also includes a display case of rotating diplomatic gifts given to America’s presidents by world leaders—from ornate cultural artifacts to unexpected curiosities, like the peanut ring gifted by Mexico’s First Lady Carmen Romano de López Portillo to Rosalynn Carter in 1977; and the Waterford crystal cowboy boot presented to Ronald Reagan by Fergus O’Brien, Lord Mayor of Dublin, Ireland, in 1982.

Uncle Sam Presents Gallery

A seven-minute film features a very small sampling of the 450 million feet of film at the National Archives. Starting with one of the early Wright Brothers’ flights, which is believed to be the first government-sponsored film, the film shows historic moments as well as glimpses into daily American life. One clipping shows “Duck and Cover,” a cartoon video featuring Bert the Turtle during the 1950s to teach students what to do in the event of a nuclear attack; while another from 1960 stars Smokey Bear teaching kids about the danger of forest fires.

Innovation Nation Gallery

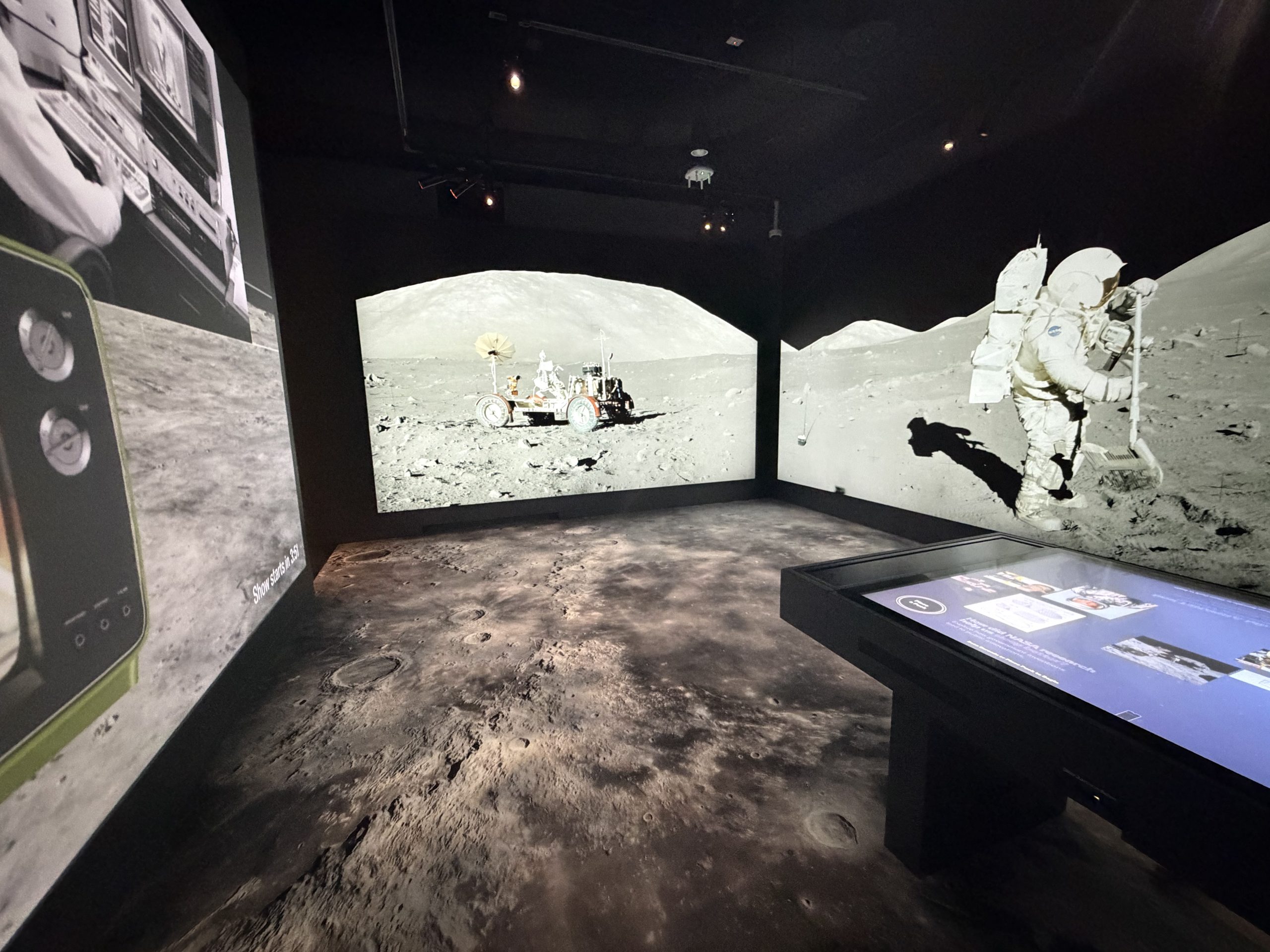

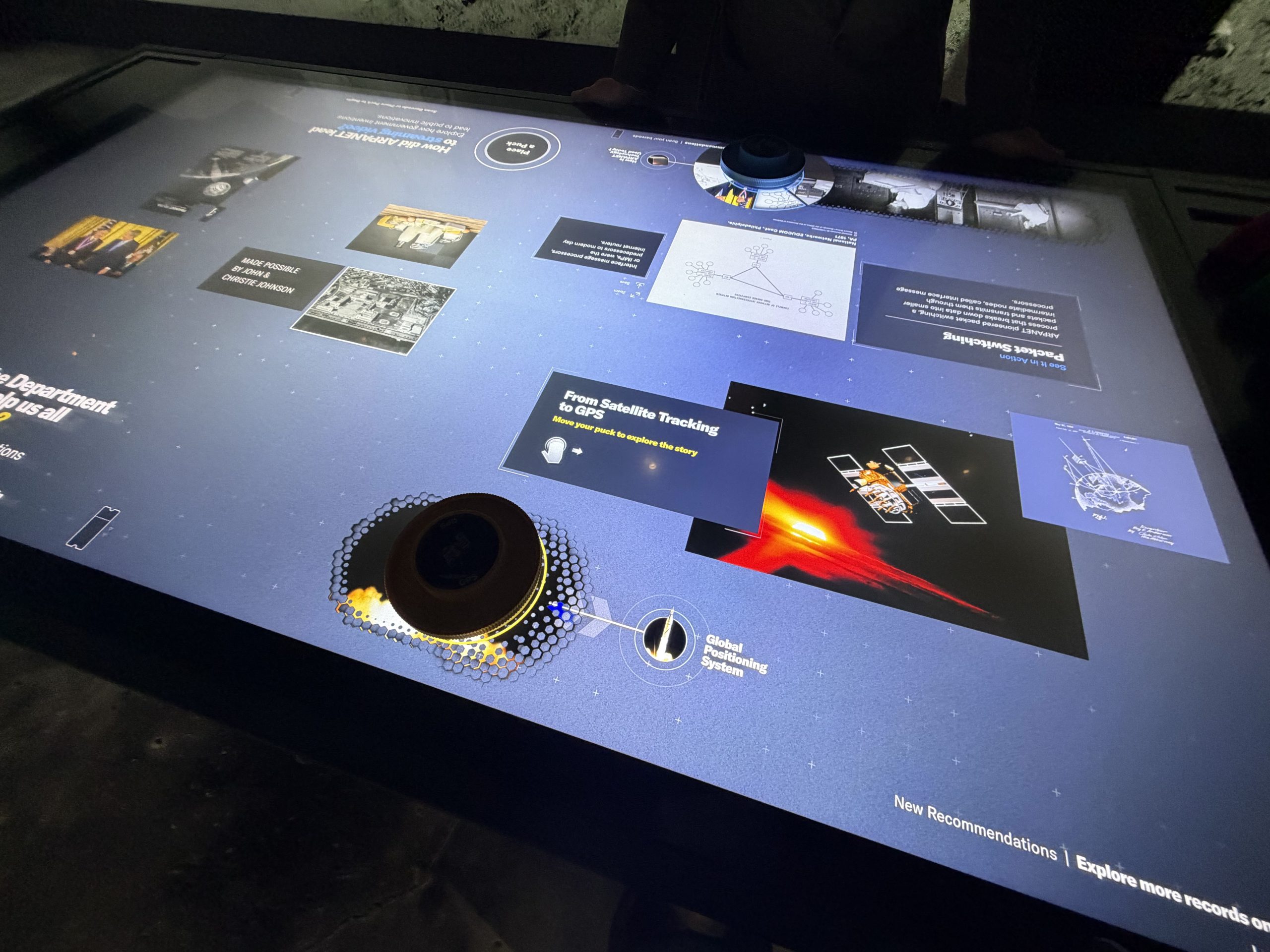

You are on the moon! Lunar imaging on the walls and floor decorates this gallery devoted to documents detailing the evolution of technologies sparked by the U.S. government. An AI-generated digital table allows you to dive deeper into how the Apollo space program led to, for example, better athletic shoes and GPS via materials science and manufacturing spin-offs.

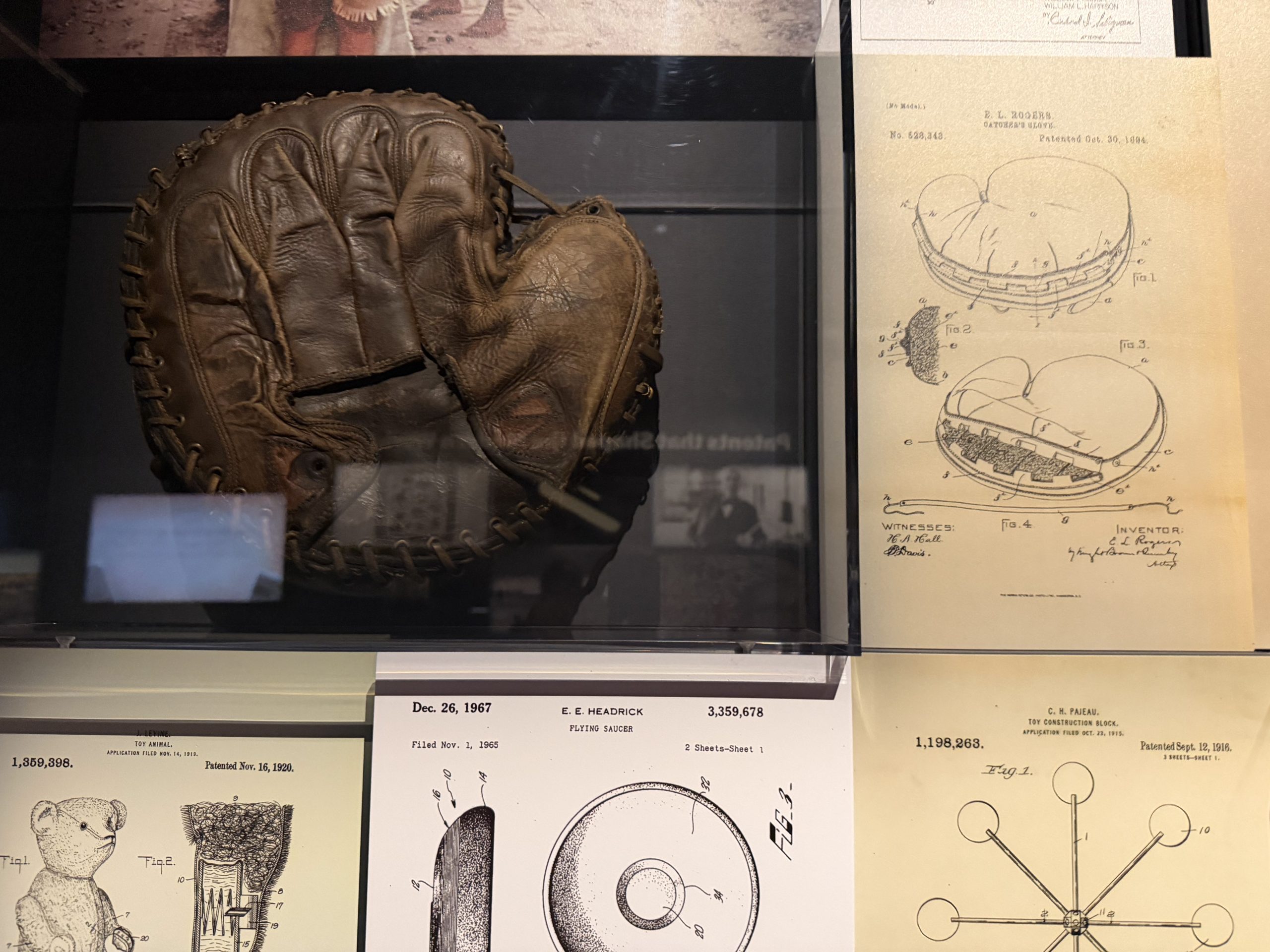

Next door is the Patent Gallery, displaying some of the nation’s most amazing patents—from anesthesia (1846) to E. L. Rogers’ catchers’ glove (1895) to Ruth Handler’s Barbie Doll (1959).

“Your National Archives in Action” Gallery

The experience culminates in a series of interactive portals where you meet people who have used personal stories to shape their research—ranging from private citizens to filmmakers and historians. One striking example is an Ohkay Owingeh pot made by artist Gregorita Trujillo around 1974, displayed at an event attended by President Richard Nixon and later rediscovered in the Archives after her great-grandson, Anthony Trujillo, reached out with an inquiry. At the other end of the spectrum is David Grann, who reflects on his archival research for Killers of the Flower Moon, illustrating how individual narratives can resonate on a global scale.

An interactive table shows you how to find out if your own descendants—or even you—are in the Archives. Finally, two kiosks let you explore Ancestry.com’s records to find relatives based on censuses up to 1950 (based on a 72-year privacy law, meaning the 1960 Census won’t be public until 2032).

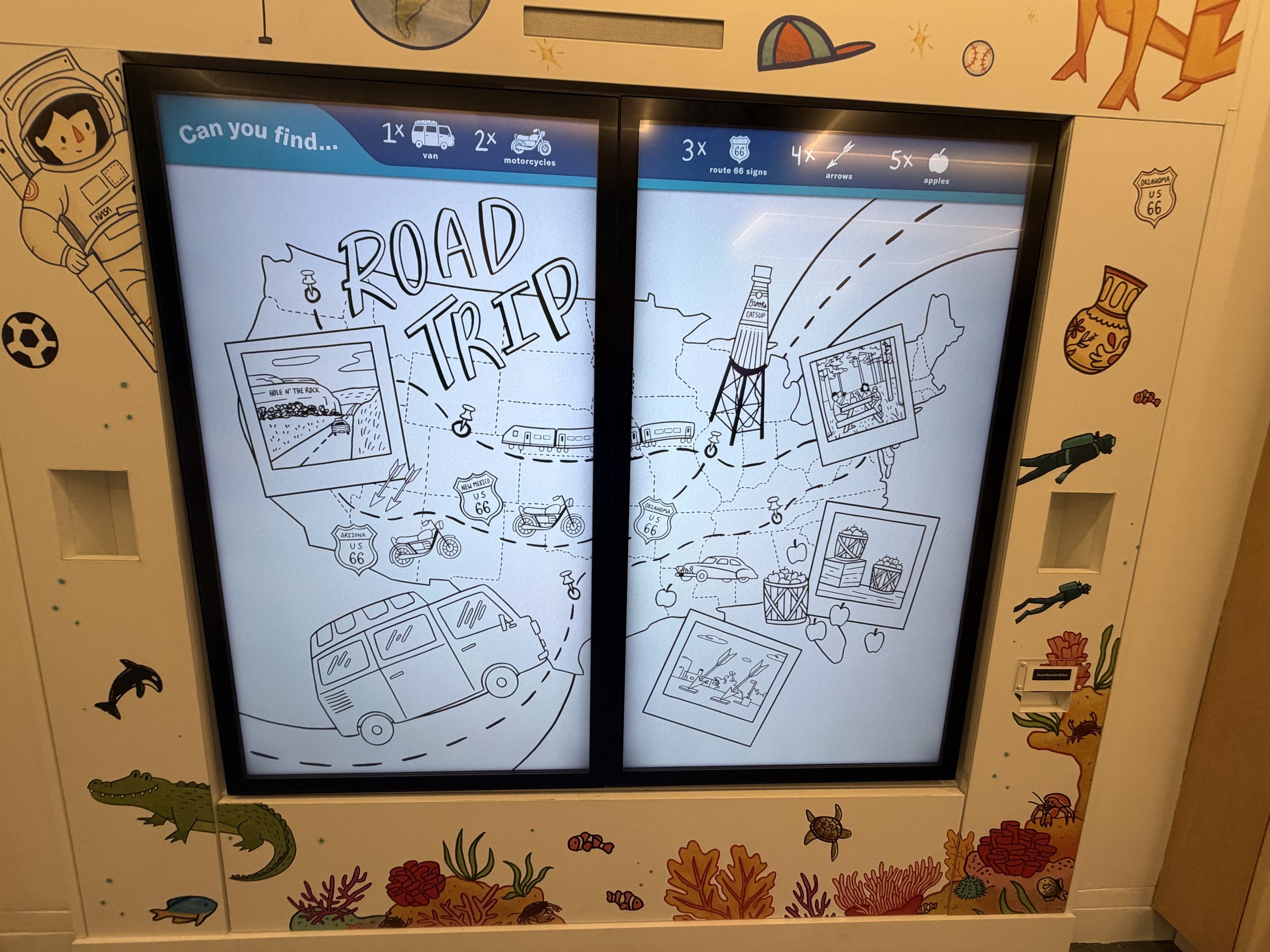

Discovery Center

Kids—be sure to head to the opposite side of the Rotunda, where the Discovery Center beckons with the dazzling look of a vintage arcade. Parents—no need to tell them the center is a playful, fun way to introduce the younger set to the Archives’ vast collections. Hands-on “games” range from taking a stand during a 1950s congressional hearing on comic books (are you for or against?) to re-creating dance moves using historic films. One of the most popular features is the interactive photo booth, where you can snap your portrait and place yourself in an iconic historic scene.

Your American Story

At home, you can sign in with your QR code to download every record you saved—your own mini archive to explore after your visit. And when you come back, you can choose an entirely new topic and, along with rotating artifacts and updated content, walk away with a completely different experience.

Side Dish

If you need a bite during your visit, the lower level of the National Archives houses Charters Café, a casual spot for salads, sandwiches, burgers, and drinks (open weekdays). Or step outside into Penn Quarter, where standout dining options abound—most famously Jaleo, José Andrés’s celebrated Spanish tapas restaurant, just a three-block stroll from the Archives.

By Barbara Noe Kennedy. Barbara left her longtime position as senior editor at National Geographic Book Publishing in 2015 to go freelance as a travel journalist. She writes stories about art, history, culture food and drink, and social justice for various publications, teaches classes on travel writing and destinations, and writes books. barbaranoekennedy.com.

All Photos including the top photo are by Barbara Noe Kennedy unless indicated otherwise.