For most people, the name “Jackson Hole” evokes rugged peaks, glacial lakes, and charismatic megafauna—the American Alps. But for those who have visited Jackson Hole, it also brings to mind a culturally rich Old West town with a vibrant gallery and museum art scene. Recently, Jackson’s iconic landscape and its arts are becoming increasingly intertwined, thanks to innovative public art projects and artists.

“There is this inherent tension when you live in one of the most beautiful places in the world, of how could you possibly make it better,” explains Jackson Hole Public Art Executive Director Carrie Geraci. “But we have world travelers coming here who have been to piazzas and incredible places like Machu Picchu, who have seen how the built environment can be as inspiring as the natural environment. So, part of our modus operandi has become putting in that extra effort into the built environment.”

Jackson Hole Public Art, a fifteen-year-old nonprofit dedicated to creating community-minded, artist-driven projects for public spaces, was founded at an opportune time, when the town’s architectural vernacular was transitioning from heavy, overwrought western-style log buildings to cutting-edge modern architecture. Important public spaces at the time, like the Teton County Library, designed by Will Bruder, or the Grand Teton National Park Visitor Center, designed by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, signified a new open-mindedness that art and architecture didn’t have to simply defer to their surroundings, but could be in a novel and interesting dialogue with it.

Once this door was opened, early innovators like John Simms and Ben Roth, found they could use public arts for more than just creating a dialogue with the natural environment, but as a tool to understand it better.

Ben Roth created Buffalo Wallow from fir and pine trees that were harvested locally to reduce wildfire risk. Roth studied beaver runs, dens, and nests before designing the interactive piece for a popular downtown greenspace.

Strands, a glass installation on the exterior of the town’s welcome center, explores bison and grizzly DNA. John Frechette worked with biologists and a local high school to map the DNA fingerprints of bison and grizzly bear species indigenous to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Frechette then magnified the strands into a colorful sequence scaled to the building. He then made 84 glass bricks and mapped them on a metal screen that wraps around the building’s exterior.

Works like Thea Alvin’s Flow demonstrate not only the artist’s quest to understand the natural world better through art, but also an attempt to invite the viewer to join them in that quest. Alvin’s Flow, a dry-laid stone enclosure at a popular community park along the Snake River, draws inspiration from various patterns found in the park, such as the flowing water of the Snake River and the movements of geese, elk, moose, and deer. Alvin designed an open maze with winding, interconnected walls that reflect these natural phenomena, allowing visitors to experience them firsthand as they move through the structure.

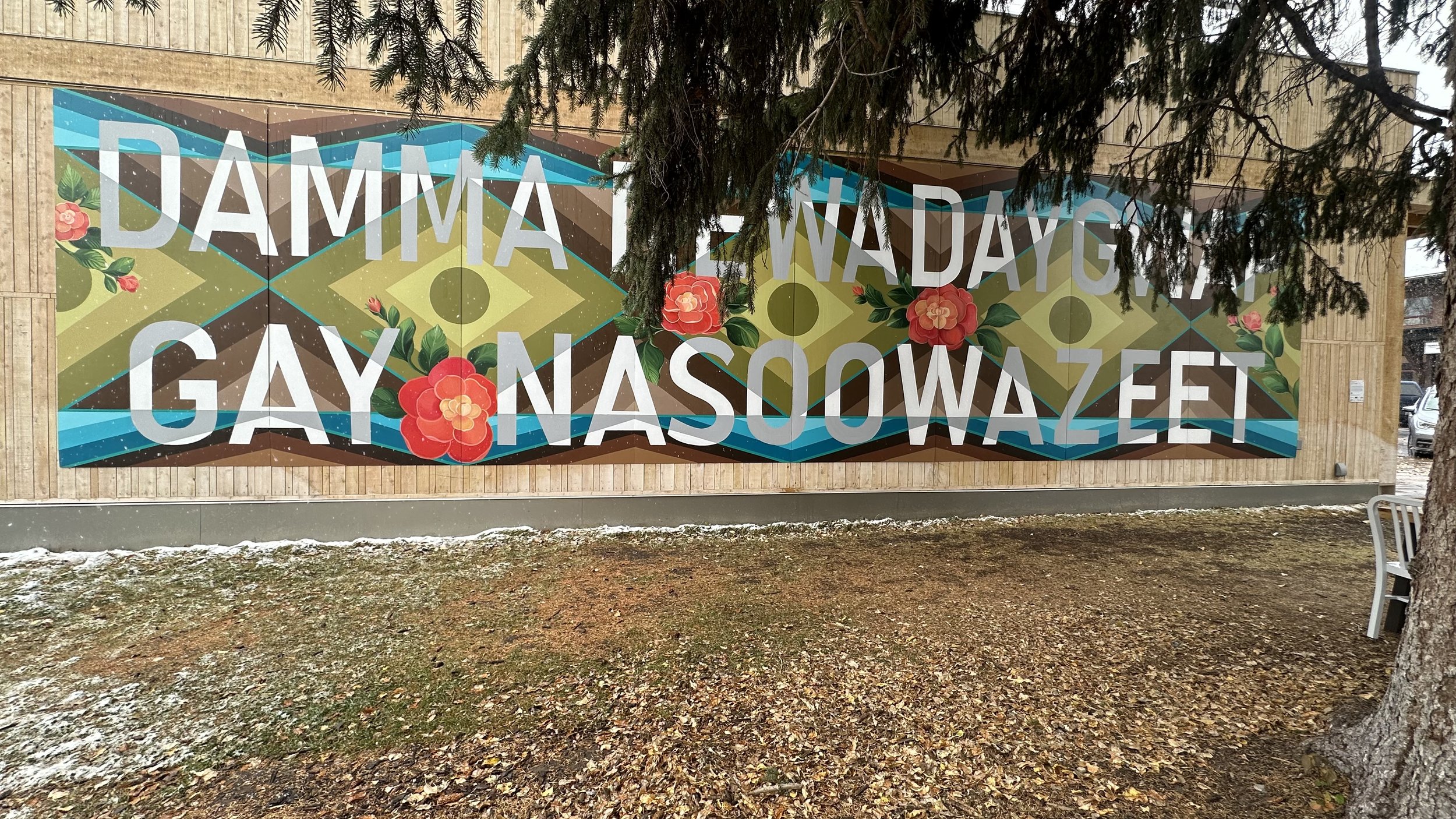

Artists have also explored the relationship between place and identity in relation to the natural world through public art in Jackson. Nanibah Chacon’s mural, Never Forget Our Language, challenges the dominant Euro-American narrative on identity and land. Her mural acts as a conceptual billboard, reclaiming space for the Shoshone people, whose ancestors called this region home. By incorporating Shoshone language, the mural connects the land, culture, and people, emphasizing their deep-rooted relationship.

Willow Grove, near a busy intersection, acts as a landmark in a natural history story map. Sculptor John Fleming created tall, illuminated metal willows that evoke the wetlands that covered the area decades ago before developers rerouted Flat Creek away from Broadway to expand the town’s footprint. The work feels like a layer on a GPS map has been uncovered, inviting viewers to reflect on the changes to and impacts on the natural environment.

Lastly, Jackson’s public art offers opportunities for viewers to personally engage with nature in a way that art on a wall cannot. Thus, it is not only the artist who is engaging with nature, but the viewer as well.

In Jackson, this engagement can never begin soon enough. Works like Buffalo Mountain and Little Buffalo Mountain by Stewart Steinhauer at the National Museum of Wildlife Art invite children to play on the art; a wildly different experience than they are used to inside a gallery or museum.

Finders Keepers, by Patrick Daugherty, invites viewers—young and old—to explore the inner depths of his ‘stickwork’ creation, sparking curiosity and wonder as they walk through the piece, mimicking the experience of any outdoor adventure.

Jackson Hole hosts nearly 50 public artworks, commissioned by Jackson Hole Public Art, local businesses, the municipal government, private property owners, and the National Museum of Wildlife Art, among others. Jackson is so rich in public art you might never visit a museum or gallery and still feel like you’ve had a deeply artistic experience in the Tetons.

Some works of permanent public art have become tourist mainstays, such as the historic Antler Arches on the town square or the Battle of Wills by Bart Walter at the Jackson Hole Airport. However, in the spirit of environmental stewardship and sustainability, many public art installations are commissioned and designed as ephemeral, temporary, and leave-no-trace pieces. “In a town with very little private land and a large amount of public land, having a light footprint is crucial,” Geraci says of working in Teton County, which is the size of Rhode Island, and only 3% of it is privately owned.

Public art in Jackson Hole is expanding as a medium that enhances our understanding of place, community, environment, and history. “The artist is engaging in a dialogue with the community and environment,” Geraci explains. “Public art represents today’s art but tomorrow’s history. It is going to tell the story to the next generations.”

By Katherine Wonson, Writer, Founder and Principal of Old School Heritage Solutions

Featured photo: Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center, Grand Teton National Park. Photo by Acroterion.