Creative people have long gravitated to New York’s beautiful Hudson Valley for inspiration. Among these was the influential industrial designer Russel Wright, who helped make good modern design accessible to middle-class Americans in the mid-20th century. At Manitoga / The Russel Wright Design Center, his country house, studio, and garden in Garrison, Wright transformed the site of an abandoned quarry, designing living spaces and woodland trails, an intensely personal project that reflected his artistic principles and deep appreciation of nature. Today visitors can find their own inspiration during a guided tour of the house or a hike on the trails. Manitoga is also part of the region’s creative resurgence, featuring installations and performances, and partnering with other organizations.

Manitoga is especially appealing when colorful fall foliage provides a backdrop for special programs. On September 21 and 22, Trisha Brown Dance company will present “Trisha Brown: In Plain Site,” in sites around the grounds. From September 13 to November 18, Manitoga will present “The Moss Room,” with outdoor sculptures by Alma Allen and Bosco Sodi in the former quarry woodlands. Kate Orne, founder of Upstate Diary, curated the exhibition, which was co-organized by New York’s Kasmin gallery.

Russel Wright and Manitoga

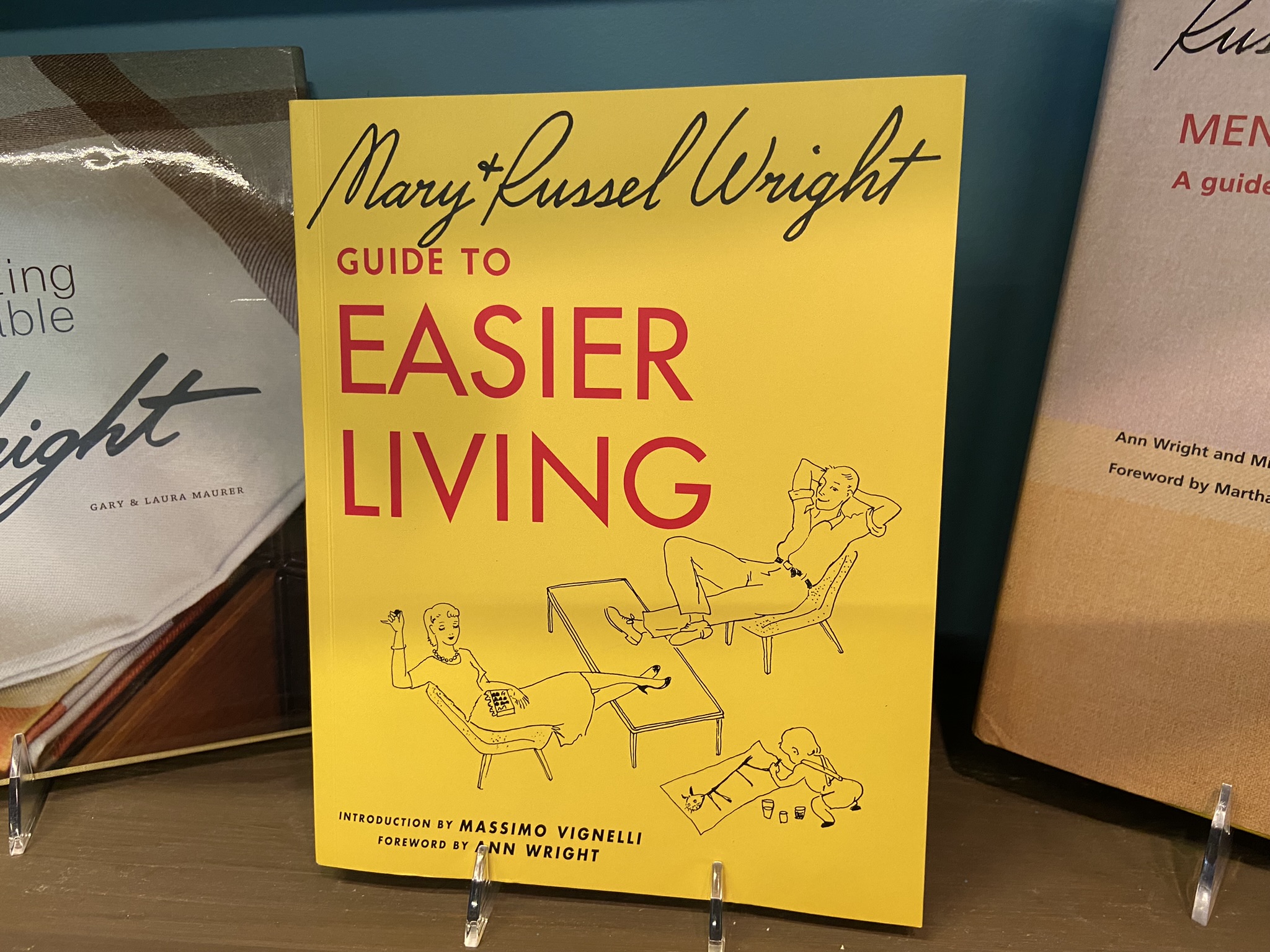

Russel Wright (1904–76), along with his wife and business partner, Mary Einstein Wright (1904–52), created a lifestyle empire based on the belief that “good design is for everyone.” His affordable modern designs for tableware, housewares, furniture, and textiles appealed to a changing, more suburban, less formal America. Mary Wright was a designer and master marketer, coining the term “blond” for light-hued wood and working with department stores to set up displays of Wright’s designs in room settings. Russel Wright’s colorful, organic American Modern tableware, introduced in 1939 (Bauer still produces some items), was a sensation that sold 200 million pieces by 1959. The couple even wrote a best-selling book, Guide to Easier Living, in 1950. Along with charts, lists, and illustrations for setting up an efficient modern home, it espoused now-popular concepts such as open-plan living spaces (seen in the house at Manitoga) and casual entertaining, from picnics to buffets.

The Wrights lived in a triplex apartment on Park Avenue in New York but loved the Hudson Valley. In 1942 they purchased 75 acres, a former quarry and logging site, in Garrison, 50 miles north of Manhattan. They spent time away from the city in a small house there, planning a modern home. Sadly, Mary Wright died in 1952, when the couple’s daughter, Ann Wright, was two. Russel Wright collaborated with architect David Leavitt on the house and studio, which was completed in 1961. LIFE magazine featured it in 1962 as “A Wonderful House to Live In.” The designer moved there full-time in the mid-1960s. Wright died in 1976, and the nonprofit Manitoga, Inc. was established in 1984. Manitoga was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 and added as a National Historic Landmark in 2006. It’s also a member of Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios. Since seasonal public house tours began in 2010, Manitoga’s unique integration of nature and modern design have made it increasingly popular—around 8,000 people visited in 2023.

Experiencing Manitoga

Russel Wright named the site Manitoga, from Algonquin words meaning “place of great spirit.” As visitors approach along a wooded path, the house comes into view, its low-slung, rectilinear buildings of stone, glass, and wood perched on the rocky edge of what is now a pool in the former quarry. The scene expresses harmony with nature, albeit a harmony carefully designed by Wright. He moved the 30-foot waterfall that spills into the pool (which guests swam in) and spent years creating the paths and landscape around Manitoga, bringing in boulders, planting trees and native plants, and mapping trails to create an optimum dramatic experience for himself and his guests. Daughter Ann Wright called the house “Dragon Rock” after a shape she observed in the rock lining the pool.

Inside the house, large windows bring nature in and can be opened to allow access to outdoor terraces, and the rock ledge of the former quarry forms part of the wall and a fireplace in the house. Pieces of rock serve as steps between different levels. The post-and-beam architecture and details such as the uncluttered spaces and concealed storage areas show Leavitt’s and Wright’s interest in Japanese architecture and design. The kitchen is sleek and white, and modernist furniture and home goods by Wright and other designers of his time fill the rooms. A vine-draped pergola connects the house with Wright’s studio and bedroom; his desk overlooks the boulder-strewn hillside. Although Wright urged homeowners to be practical, he experimented with materials and natural elements here. For example, the house has a green roof; hemlock needles are pressed into the green plaster in the living room; butterflies are pressed between plastic sheets as part of a wall; and birch bark covers a door. Guided tours end in the Russel & Mary Wright Design Gallery, which opened in 2021 and displays more than 200 examples of objects designed by the Wrights over the decades.

Visitors can sign up (book ahead; groups are small) for a 90-minute tour or some specialty tours. It’s also worth hiking some of Manitoga’s several miles of woodland trails (a map is available on-site). Russel Wright felt that the landscape and trails, helping people become closer to nature, were even more important than the house. As Vivian Linares, Director of Collections, Interpretation and Preservation, said, “We hope visitors will be inspired by the story of the Wrights and Manitoga, its unique sense of place, and the wonderful interplay of nature and design.”

Community Connections

Manitoga reaches out to the local and broader community in many ways. Manitoga’s trails are open daily and are free to the public (a donation is requested), thanks to a partnership with the Open Space Institute. Themed guided hikes (fee) explore aspects of the woodlands. Other on-site programs and events include bringing in musicians and offering opportunities to volunteer on landscape workdays.

Educational partnerships and workshops are important, too. Students and faculty from institutions such as Pratt Institute and the School of Architecture of Madrid have interacted with the site. Manitoga has a continuing relationship with the Felix Organization, a nonprofit that provides enriching experiences for young people growing up in the foster system.

Since 2014, the ART + DESIGN Residency Program has invited artists working in different media and composers and choreographers to share their creative responses to Manitoga. In summer 2024, The Source of Everything exhibition, presented in the house and studio, displayed the work of seven Hudson Valley artists who feel, as Wright did, a deep connection to nature and how it inspires us.

Manitoga has connected to the Hudson Valley and beyond through object loans and collaborations such as a 2024 exhibition at Studio Tashtego in Cold Spring. It participates in events such as the Hudson River Valley Ramble, which celebrates the region’s history and culture throughout September. The annual Upstate Art Weekend, a four-day, ten-county summer event, attracts locals and visitors to explore the region’s flourishing creative scene. More than 145 arts organizations and temporary exhibitions were highlighted in 2024, including Manitoga.

Linda Cabasin is a travel editor and writer who covered the globe at Fodor’s before taking up the freelance life. She’s a contributing editor at Fathom. Follow Linda on Instagram at @lcabasin.

Featured image: The studio building is on the left, linked to the house below by a pergola. Photo by Mike Squires