Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill in its heyday numbered some 500 members of the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing. It was 1774 when Ann Lee, a Quaker whose beliefs had been the source of persecution and imprisonment, arrived in New York from England with eight loyal followers, who believed she was Christ incarnate. One vision had enjoined her to leave for America where she could prosper.

On a donated piece of land, north of Albany, New York called Niskayuna, she and her disciples made their home; visitors came and were deeply moved by watching how these men and women “shook out” their sins in frenzied whirling dances for which they were nicknamed “Shakers.” Soon Mother Ann’s powers, avowed as miraculous, gained converts, and with her own proselytizing, helped spread the word. Later, in 1784, members completed the first Shaker meeting house at New Lebanon, New York; in that same year, Mother Ann died, leaving behind the roots of Shakerism.

The New Lebanon Shakers established the organizational structure of the community. The rules governing Shaker life were the Millennial Laws; they detail the order of worship as well as the duties of the members, use of property and quality of work. Although people were divided into “Families,” the word itself had a very general meaning. All were brothers and sisters in a consecrated communion of the spirit, a spiritual link relating every Shaker to Mother Ann as well as to every other Shaker.

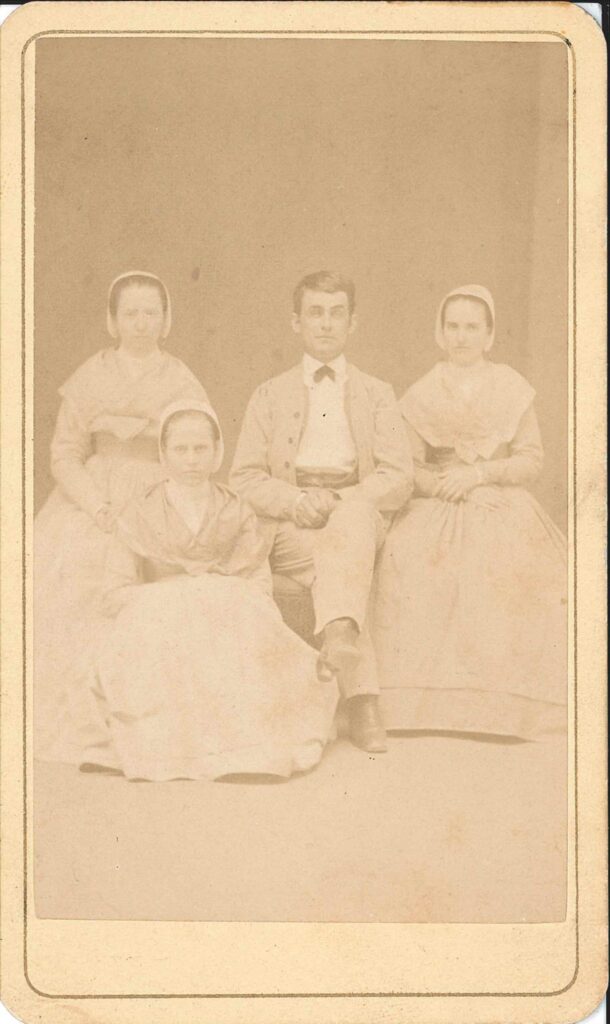

The basic tenets of the faith were celibacy, communal ownership of property, confession of sins and separation from the world. The Shakers also advocated equality of the sexes and pacifism, social principles often met with scorn at the time.

Communities formed not only in New York, but also in New Hampshire, Connecticut, Maine and Massachusetts. In 1805, three Shaker brethren left for the Midwest to seek converts and establish communities. In the following ten to fifteen years, communities were established in South Union and Pleasant Hill, Kentucky as well as in Union Village, North Union and Whitewater, Ohio.

The original Elders, appointed by Mother Ann, were responsible for setting up the Order of the Ministry, a self-perpetuating hierarchy. Trustees and Elders handled business with the “outside world.” These Trustees were assisted by Deacons and Deaconesses who were responsible for different trade shops. The Shakers never let religious zeal make them blind to the fact that they must get along with the people around them, and that they must trade to survive. Although self-sufficient to a great extent, they could never produce everything necessary for survival.

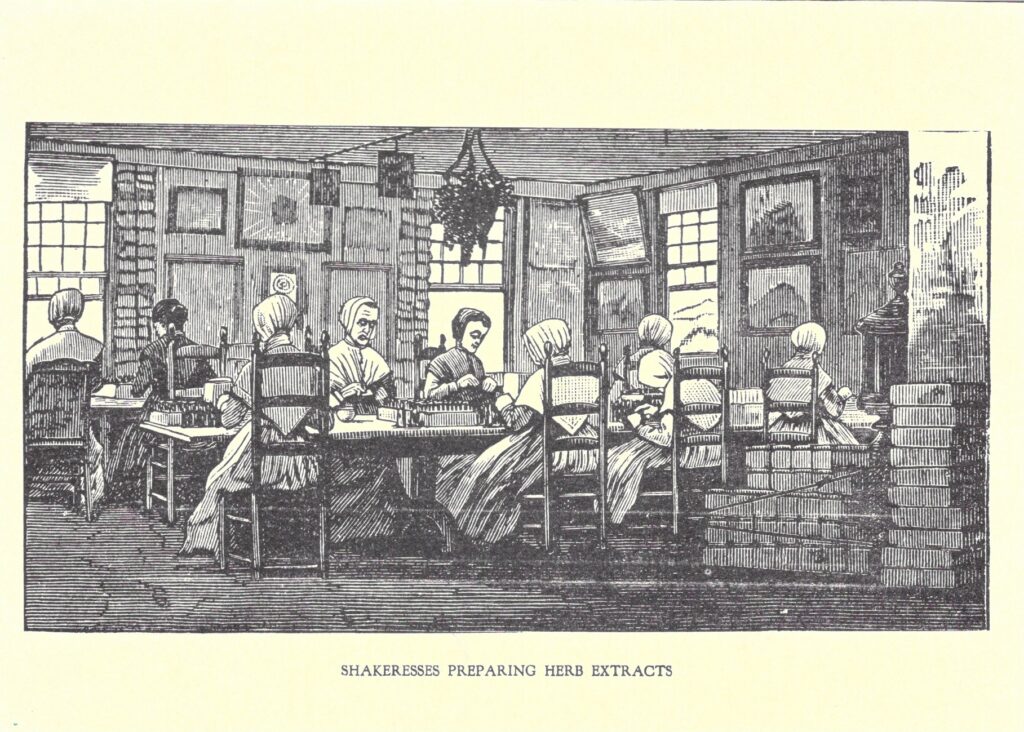

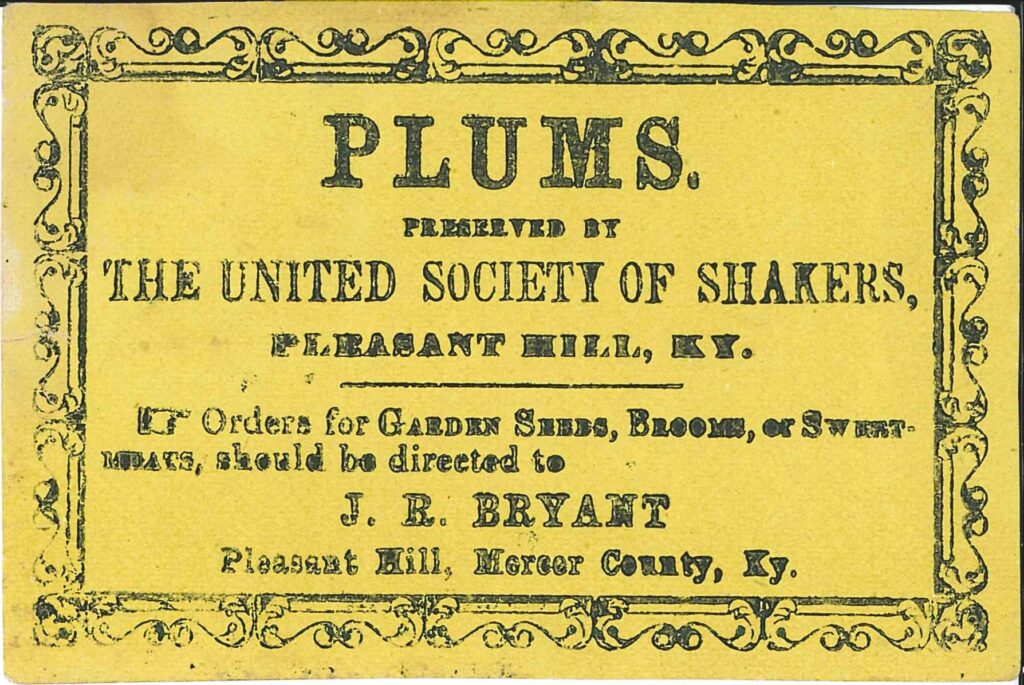

Fine craftsmanship, high quality and honesty led to success and an unsullied reputation. In 1790 the Shaker seed industry began; it lasted for well over a century. Shakers collected, grew and packaged herbs and seeds and herbal medicines. Communities had specialties: oval wooden boxes, canned vegetables and fruits, cloaks and chairs. At both Kentucky villages, products such as brooms, garden seeds, baskets, and onions for sale were loaded onto flatboats down the Mississippi.

According to Two Shaker Villages: South Union & Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, “The Shakers in Kentucky became leading agriculturalists practicing crop rotation, which they introduced to the frontier and packaging of garden seeds for sale. In addition, they sold jellies and preserves for which they were noted…At Pleasant Hill the Shakers earned an international reputation with their products, such as medicinal herbs, which were much prized abroad. The following is noted in the records of the State of Kentucky: ‘Let a stranger visit your country and inquire…for your best specimens of agriculture, mechanics and architecture, and sir, he is directed to visit the Society of Shakers at Pleasant Hill.‘– Robert Wickliffe, Senate of Kentucky, January 1831.”

The Kentucky Shakers produced their own silk from the 1820s to the 1870s. Raising silkworms on mulberry trees and weaving fine silk thread was a labor-intensive process. It took 805 cocoons for one pound of silk that was often dyed bright colors before being woven, creating iridescent scarves that comprised part of a Shaker sister’s dress.

The Shakers’ sole purpose in life was to establish God’s Kingdom on earth. Their minds, hearts and hands were devoted to this ideal. It is not surprising, therefore, that their kitchens became as holy as their workshops. Here industry and efficiency turned to meal preparation.

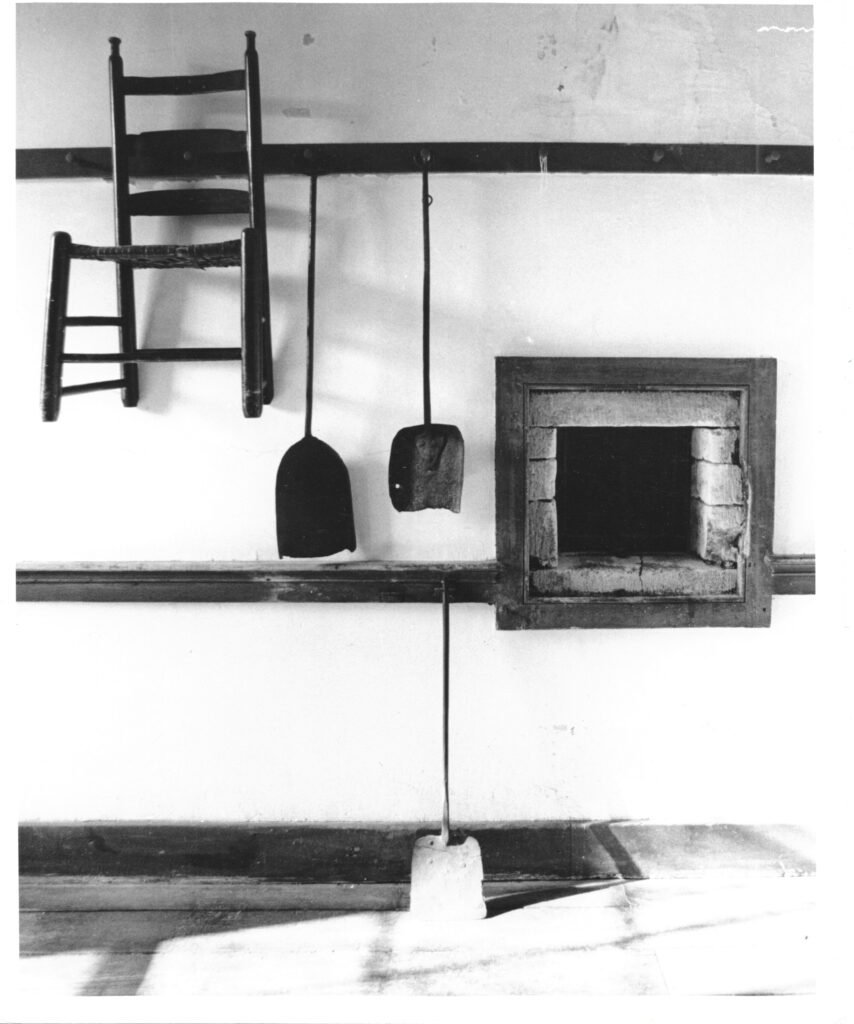

”Put your hands to work and your hearts to God” is a well-known Shaker motto. But they made no religion of work; spiritualism was at its base. Beauty was not admired for its own sake. Only “the world” could find enlightenment in the appearance of an object. Esthetics had no intrinsic value but craftsmanship did. No ornamentation obscured basic design. Functionalism and simplicity were inherent in Shaker perspective, not for lack of imagination, but because they were integral to the search for the perfection of God’s Kingdom on earth.

Like their architecture and dress, Shaker cookery expressed simplicity and a high standard of perfection. The Shakers practiced organic gardening; their plain and wholesome meals tended more and more toward vegetarianism. Meat was considered less beneficial than other foods. Historian Charles Nordhoff wrote from personal observation, “They consume much fruit, eating it at every meal; and the Shakers have always fine and extensive vegetable gardens and orchards.”

How then did the Shakers fail? The most important factor is celibacy, a major tenet of their religious beliefs. During the Civil War, there were no formal orphanages, and many orphans came to live in Shaker communities. As the industrial age took hold and manufacturing led to the accumulation of material goods and to city jobs, many Shakers chose to leave their communities. Eventually, the original religious fervor was spent, fanatical sermons became fewer and less meaningful. Younger Shakers became less interested. In a sense, Shakerism was a result of its times and gave way to the Industrial Age and big-city glitter.

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill today shares 3,000 acres of discovery in the spirit of the Kentucky Shaker utopian experiment. Home to the third largest Shaker community between 1805 and 1910, and a beacon of hospitality in its day, today it is the only Shaker Village where guests sleep in restored Shaker buildings in rooms appointed with Shaker reproduction furniture, original hardwood floors and expansive Village views.

Farming, at the heart of the community, was a model of innovation and efficiency. Shaker Village continues this tradition by employing sustainable agricultural practices while tending the garden, orchard, livestock and apiary. In addition to providing fresh organic produce for The Trustees’ Table restaurant, the farm shares lessons in sustainability with visitors.

Menus celebrate Shaker Village’s roots by featuring dishes made of seasonal ingredients. You dine on tradition: Shaker favorites and popular Kentucky classics. And Shaker lemon pie, a unique version of the American classic, made with “sliced lemons as thin as paper, rind and all,” is always on the menu.

Although the Shaker way of life is no longer, Shaker belief in the divine inspiration of work and food reveal outstanding contributions to America’s social and culinary heritage.

All photos are courtesy of Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, except as noted.

Cynthia Elyce Rubin, Ph.D. is a visual culture specialist, travel writer and author of articles and books on decorative arts, folk art and postcard history.